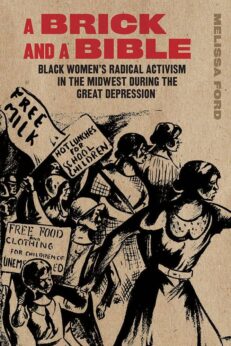

In her innovative study of four Midwestern cities during the Depression era, historian Melissa Ford reveals an emergent pattern of social crisis, involvement, and Black women’s radical activism. A Brick and a Bible examines the evidence and creates a framework for understanding this tradition of social action by Black women, naming it “Midwestern Black radicalism.” She defines this term as a “praxis-based Black radical ideology informed by American Communism” that fought racism and its deep ties to capitalist exploitation.

Further, because of the specific relation of racism, class exploitation, and gender-based oppression, Black women’s activities in this period necessarily took on what Ford calls an “intersectional” approach. While these concepts don’t exclusively apply to Black women, Ford’s study centers Black women’s leadership and actions because their stories are barely perceptible in most historical accounts of those times.

Further, because of the specific relation of racism, class exploitation, and gender-based oppression, Black women’s activities in this period necessarily took on what Ford calls an “intersectional” approach. While these concepts don’t exclusively apply to Black women, Ford’s study centers Black women’s leadership and actions because their stories are barely perceptible in most historical accounts of those times.

Deftly using local archives, Ford’s research explores why Black women turned to the Communist Party after the 1930s, given a long history of preexisting Black organizations, struggles, and movements that seemed available to them. Recall that the Communist Party was founded in 1919, and its initial conveners tended to believe that racism was simply an extended feature of economic struggle that would end when capitalism ended. This reductive theory seemed to authorize their refusal to pay special attention to what ultimately became called the “national question,” or the struggle against white chauvinism and racism. Because that approach left the Communist Party incapable of organizing a united class struggle that necessarily envisioned racial capitalism as the main systemic enemy of the working class, few Black people seemed interested at first in committing to the organization’s work.

Ford’s book details, however, a crisis in Black organizations that propelled working-class Black people toward the Communist Party. The NAACP, which had been a major leader in civil rights struggles up through the 1920s, seemed primarily concerned with middle and upper-class parts of the Black community while focusing its main efforts on court-based actions. As important as this agenda was, it seemed tangential to the immediate needs of workers thrown out of work after the breakdown of the system in 1929. With unemployment, underemployment, and poverty rates in the shocking 40-75% range in each of those cities that Ford studied, tens of thousands of Black households faced daily struggles for food, paying rent, fighting disease, as well as resisting brutal cops, racist employers, and hateful whites.

Other institutions, which had been instrumental in fostering community action during the Great Migration and finding jobs for new arrivals, such as churches, the local Urban Leagues, and charity organizations, could no longer meet the overwhelming need for employment and relief. In each of the cities in the 1920s, the Garveyite movement had provided many Black communities with radical, working-class alternatives to the primary social institutions (including new public roles for Black working-class women), but that organization’s crisis by the end of the decade led to its near collapse. In Chicago and Detroit, the emergent National of Islam drew some interest in the Black communities, but it refused to publicly campaign on political issues.

These developments meant most Black working-class people had no organizational home for the militancy they understood was needed for changing their conditions of life. By 1930, the Communist Party had significantly altered its understanding of systemic racism in the U.S. and became a leading force in the struggle against racism, exploitation, and economic crisis. Its willingness to develop Black working-class women’s leadership, its commitment to fighting job and wage discrimination, and its refusal to accept housing segregation and racist police brutality helped to increasingly identify it with Black freedom as an essential feature of working-class power.

This period of radical action and struggle saw Black women like Detroit’s Mattie Woodson, Rose Billups, Dorothy Ida Kunca, and Mary Sydney take on leadership roles in the unemployed councils, trade union organizing, and community actions that brought to the foreground issues such as food access, healthcare, and job and wage security.

Black working-class women in St. Louis set aside their fears about public action and confronted politicians, bosses, and cops. Some, like Lizzie Jones and Magnolia Boyington, were injured and even killed for their courageous stand for justice. Carrie Smith, who had led unemployed actions in the early 1930s, also went on to lead and organize the Funsten Nut Strike (depicted in Myrna Fichtenbaum’s classic The Funsten Nut Strike), ultimately winning an erasure of racist pay discrimination and improvements in health and safety conditions in the factories.

In Chicago, Black women radicals and Communist Party leaders included Romania Ferguson, Eleanor Rye, Anna Schultz, Marie Houston, and Thyra Edwards. These women could be found organizing anti-eviction struggles, relief protests, demonstrations against the racist Scottsboro convictions, and teaching other Black women how to organize labor unions. Black women led the two-week strike in Sopkin’s garment sweatshops that employed Black women, especially, to gain higher profits through a racist wage gap. Dirty, dangerous, and unsanitary conditions of work along with his demand that workers wear “loyalty scarves” angered the workers. Strike activity swiftly spread across the city and morphed into dangerous confrontations with cops who were angry that Black women in the hundreds and even thousands would occupy the streets in protest.

Similar patterns of combined community protest and workplace struggles emerged in Cleveland under the leadership of Black Communists such as Mary Tabb and Maud White. Known as “Alabama North” for its large number of migrants from that state, Cleveland’s Black communities were especially energized by the Communist Party’s Scottsboro campaigns.

Each chapter of this highly readable book follows a similar pattern. Ford details a crisis in Black organizational effectiveness that was spurred and deepened by the arrival of hundreds of thousands of Black people in industrial cities in the North during the decade before the Depression, to the emergence and solidification of the Communist Party’s militant role, led by Black men and women. Each chapter, except the Cleveland chapter, also culminates nicely with a detailed study of a specific union organizing activity centered on a strike action that uplifts that new condition of militancy. In Cleveland, the pattern emerges later in the 1930s after the Party’s strategic policy shifted from independent union activities toward popular front actions. By then, the CIO’s leadership of the left wing of the labor movement had become solidified, and this did not always include Communist Party leadership. Cleveland’s contribution to the larger Midwestern pattern thus centered more on the struggle for anti-racist measures, anti-fascism, and the elevation of women’s equality in the community and workplaces.

Ford argues that Black women’s radicalism drove new ideas about the relationship between workplace issues and household concerns, linking “fair wages and motherhood,” for example. Drawing on the reality of Black women’s lived experiences, Black Communist women leaders wrote a resolution at the founding National Negro Congress in 1936 on the triple oppression of Black working-class women. Ford calls for additional research on these topics across a larger geographical space in the Midwest to further establish her general framework of Midwestern Black radicalism.

Some minor drawbacks in this book include its awkward use of the phrase “communist propaganda” to imply that a story published in the Communist Party press was either false or misleading. The same term, with all of its inherently negative connotations, is never applied to the numerous examples of mainstream media attacks on workers, unions, strikers, Communists, and others. In addition, the book’s otherwise valuable thesis and astutely compiled evidence could be more nuanced. It seems to suggest that the Communist Party was essentially a “white” organization with which Black women “allied” themselves. Such an approach to understanding these events seems to accept a view of the Communist Party in racial terms, that it was “white,” despite numerous historical studies that reveal how Black members, leaders, and theorists shaped party policy and strategic thinking. It seems influenced by modern-day anti-communist histories that try to replicate the idea that Black people were (or are) not authentically communist, that the party simply used Black issues to gain supporters.

With these points in mind, this book is well worth an investment of time for study and, as the author states, as a basis for further research. It won the 2023 Illinois State Historical Society Certificate of Excellence in the category of “Books, Scholarly.”

Melissa Ford

A Brick and a Bible: Black Women’s Radical Activism in the Midwest During the Great Depression

Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2022

242 pp., $28.50

ISBN: 978-0-8093-3855-9

See here for ordering information.