NEW YORK—Most of us harbor strong beliefs in conspiracy of one kind or another. It could be about something as big as the JFK assassination or the Twin Towers on 9/11, whether or not anyone ever landed on the moon, or if vaccinations aren’t a big hoax. Some believe Elvis is still alive—probably some of the same folks who believe the Earth is flat. Maybe it’s something in your own life, like your high school teachers colluding to give you lower grades than you deserved because you were too outspoken in your political views, or, jumping ahead several decades, your kids conspiring to take your driver’s license away and put you in a retirement home.

Many readers of this publication possibly see capitalism itself as a grand conspiracy: Everything works together—politics, the educational system, wages, the church, the courts, police and military, foreign policy, male supremacy, race hatred—to make the rich more powerful and the working class impotent.

Plenty of evidence lately confirms how much conspiracy we believe there is in the world—and also how much of it actually exists. Is the watermark of Hungarian World War II refugee, now American billionaire George Soros truly in every liberal and progressive movement (such as funding the immigrant caravan now upon our southern borders)? Was there a master plan behind the tampering with the 2016 presidential election, and if so, who designed it and pulled the strings?

“Everything Is Connected: Art and Conspiracy” is the first museum exhibition on this subject, exploring how artists have dealt with this perennially provocative topic from 1969 to 2016. Seventy works by 30 artists in a wide array of media are currently on view at the Met Breuer, through Jan. 6, 2019. It’s worth a visit, and may get you thinking about what you believe to be true, and why you believe it.

Art aficionados know the building on Madison Avenue as the former Whitney Museum, which has recently relocated to a spiffy new facility in trendy Chelsea overlooking the Hudson River. The Metropolitan Museum of Art has taken over the facility as a branch of its activity. The Breuer identifies itself as “Modern and contemporary art reimagined in an architectural icon.”

The show veers in two directions. One is the factual and the other the lyrical and fantastic. An artwork illustrating the former appears soon after you enter the space. At first glance Alessandro Balteo-Yazbeck’s 2006 “UNstabile-Mobile (from the series Modern Entanglements, U.S. Interventions)” looks like a huge standing Alexander Calder mobile, and you wouldn’t know that it’s anything other than that except by reading the didactic panel on the wall. The shadows cast on the ground by the fixed floaters exactly replicate a 2001 Dick Cheney Energy Task Force map of the Iraqi oilfields that the American invaders in 2003 hoped to secure for U.S. companies (such as Cheney’s own Halliburton)—as in the classic imperialist koan, “How did our oil get under their sand?”

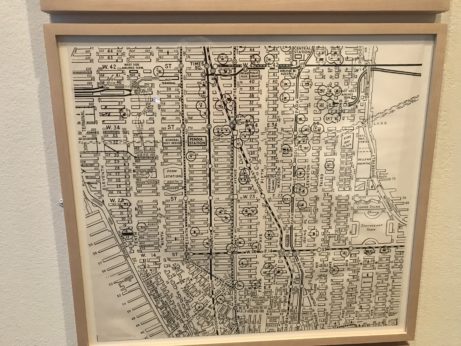

Another example of the factual is a series of maps of New York City produced by artist Hans Haacke, “Sol Goldman and Alex DiLorenzo Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, a Real-Time Social System, as of May 1, 1971,” that show block by block, building by building, how much real estate was owned by a tiny handful of landlord magnates who, once they were exposed, hastened to set up a vast collection of shell companies purporting to be the corporate “owners” of the properties, so as to disguise their actual interconnected relationship. This work has an interesting history. It was scheduled to be included in a solo artist show at the Guggenheim Museum in the spring of 1971, but the artist refused to withdraw it from his exhibition, resulting in the museum director’s canceling the show and the curator being fired. Corporate control over the arts revealed its high price.

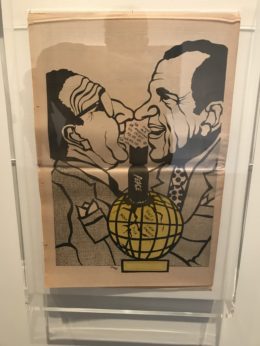

In the more fantasy-oriented artworks, the creators veer off into single-minded explanations of worldly phenomena, slicing and dicing the evidence to support their point of view, ignoring what doesn’t fit into the scheme. Just how systemic and planned out was the pattern of subjugation of communities of color? If Henry Kissinger can be identified as attending various high-level meetings (his head circled in red as if in a crime photo), does that mean he was the controlling presence deserving to be singled out as chief instigator? To what degree were isolated mental patients treated with untested drugs, such as LSD, as part of CIA mind-control experimentation—the subject of Sarah Anne Johnson’s sculptural inquiry?

Yet in many cases what appeared at the time to be fanciful extrapolations of the brain did turn out to contain much truth. We do know about the Reagan-era campaign to flood inner cities with drugs, and we have ample documentation showing Kissinger’s hand in Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos, Chile, Indonesia and East Timor.

The show has much more, about JFK, Watergate, AIDS, education and other themes. We often rely on artists to have a sixth sense about the world, pointing us to what we don’t know yet but will turn out to be.

The Met Breuer is located at 845 Madison Ave., New York 10021. Hours are Tues.-Thurs., 10 am-5:30 pm; Fri. and Sat., 10 am-9 pm; Sun., 10 am-5:30 pm. For further information see the Met website.