June marks the month-long celebration of Pride, a nationwide—and now global—acknowledgment of the queer identity and the free expression of the LGBTQ community. While the annual festivities are often a moment for LGBTQ individuals to rejoice, they also serve as a commemoration of the riots that sparked the gay rights movement nearly 50 years ago. Behind the rainbow flags and multi-colored parades, Pride stands as a reflection of the progress made over several decades and as a testament to the prolonged fight for equal rights still going on today.

Not many outside of the queer community would guess that the national celebration is predicated in anti-policing and anti-authoritarian sentiments. At the time that Stonewall took place in June 1969, the general public’s perception of homosexuality was still predominantly negative; same-sex relationships were heavily stigmatized. In many states, homosexuality was deemed a “mental illness” and subject to inhumane methods of gay conversion therapy (a practice which has still not been totally eliminated). Cops often exploited anti-sodomy laws in the 1950s and ’60s to target LGBTQ (an acronym that only came along much later) people and were known to frequently raid gay bars. Police were direct agents of the state, enforcing homophobic mandates and legislation.

In the late Sixties, leading up to the Stonewall riots, existing as an openly gay person remained a relatively dangerous activity. It was during this time that gay bars began to thrive, however, providing safe, and oftentimes discreet, places of refuge. In New York City, the (relative) success of the gay bar scene was in possible in part due to its affiliation with the mafia, which controlled Manhattan’s West Side and Greenwich Village, where most of the gay bars were located. The police were consistently paid by the mafia to stay away from specific bars, including the Stonewall Inn, a hotspot for queer nightlife. In exchange, the mafia went unbothered and was able to profit by overcharging gay patrons for services they could get nowhere else.

Bribing law enforcement only prolonged the inevitable profiling of queer communities, though. Police would often track popular gay bars as a way to target Black and brown trans and gender non-conforming individuals. Cops raided clubs after hours and arrested people who they deemed as not wearing “gender appropriate” clothing.

When the New York City police raided the Stonewall Inn during the early hours of June 28, 1969, the LGBTQ patrons had finally had enough. As cops began to get increasingly aggressive with the growing crowd, people began resisting arrest, sparking outrage from bystanders and quickly escalating an already hostile situation.

The police forces were vastly outnumbered during the incident at Stonewall and attempted to barricade themselves inside the bar, but angry rioters outside broke the windows and set the establishment on fire, forcing the police back outside. The incident at Stonewall sparked a series of demonstrations, ultimately stretching into six days of protests. The Stonewall riots were later credited as the catalyst for the modern gay rights movement in the United States, and the landmark bar eventually became recognized as a national monument.

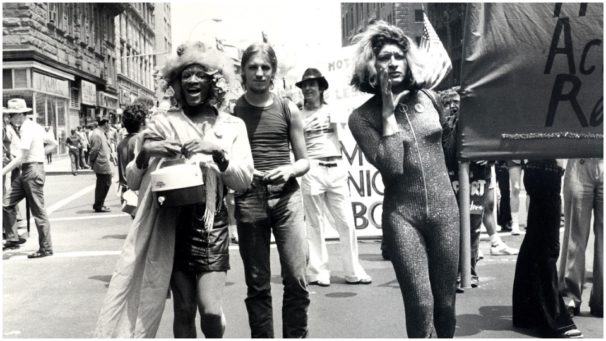

Among some of the leading voices of the gay rights movement who first rose to prominence at Stonewall were people like trans rights activists Marsha P. Johnson, credited with throwing the first brick that night, and Sylvia Rivera. Both are considered “foremothers” of the gay rights movement and experienced a number of run-ins with the police throughout their time as organizers. Johnson was a Black trans sex worker who struggled with chronic homelessness and found herself constantly locked behind bars. Similarly, Rivera also spent years dealing with severe substance abuse issues and struggled to find secure and housing. The two friends opened STAR House, a community center for homeless LGBTQ youth, which was named after their activist collective, the “Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries.”

The legacy of Pride is rooted in the work of Black and brown trans women like Johnson and Rivera who were profiled and brutalized by the criminal justice system. This is, in part, why the increased presence of law enforcement at Pride festivals has been a divisive issue within the community the last few years.

While “security” seems to be a commonplace mandate for large gatherings, chronicled evidence of police violence against people of color have led many activists to demand change to Pride festival policies concerning police presence. Even today, research from the National Coalition for Anti-Violence Programs indicates that transgender people are 3.7 times more likely to experience police violence compared to cisgender persons. This has led many to organize separate Pride events, such as the Dyke March, that are more centered around the demands of Black and brown LGBTQ folks.

Jewish trans activist and Chicago Jewish Voice for Peace organizer Stephanie Skora says increasing numbers of people are moving away from mainstream Pride gatherings because “historically speaking, police have been overtly hostile to queer and trans communities, especially those of color.” According to Skora, it is a logical step that the most marginalized parts of the LGBTQ community are moving away from events in traditional gay neighborhoods, such as Boystown in Chicago, where police inclusion at Pride events is often welcomed.

“Stonewall and its predecessor, the 1966 Compton’s cafeteria riot in San Francisco, were both anti-police demonstrations led by trans women and spurred by the refusal of police to allow trans women to simply exist,” Skora says. “Spaces like Dyke March come as a direct response to that legacy and an understanding that we can exist without fear for our safety.”

Even today, Black and brown queer organizations are constantly pushing back on mainstream Pride events as a way to express their disdain of increased police presence at events. Just last year, a coalition of queer and trans people of color in Columbus, Ohio, were accosted by police and arrested during a peaceful disruption at Pride. Four young activists made national headlines when the graphic video of the demonstrators went viral. The arrest of LGBTQ people of color at Pride events is indicative that law enforcement presence still poses a threat to the community, even if not everyone is ready to recognize that yet.

The modern “gay rights movement” was launched when people refused to accept the criminality assigned to them simply because of who they were. Whether gay, trans, gender non-conforming, or drag queens, they were all “othered” by mainstream society. In the queer community today, this false narrative of “criminality” still surrounds some members. It gets expressed in the targeting of sex workers and the racial profiling of Black and undocumented LGBTQ people. State-sanctioned violence thus remains a threat for many at Pride events, and until the direct enforcers of that violence are removed, many people will never be able to truly exist safely and freely.

Comments