When thinking about what incarcerated people need, perhaps a library is not the first thing that comes to mind. However, the population within prison walls is typically one that reads more than those on the outside. As a public librarian, I’ve long been keenly aware of the positive role prison libraries play in the lives of incarcerated people, but I also knew that recently things have been changing—and not necessarily for the better. Consultations with other professionals in the field confirmed it: The creep of profiteering corporations into prison libraries is increasingly threatening the access of incarcerated people to books.

Sarah Shotland of Words without Walls, a creative writing program for prisoners in Pennsylvania’s Allegheny County Jail, told the Pittsburgh Current recently, “One of the things you learn when you’re a teacher in these classes is that people are desperate to read.” During the pandemic, the Allegheny County Jail is operating on a restricted schedule, with inmates allowed to leave their cells for only one hour a day, according to Public Source. For many, there’s little else to do besides read.

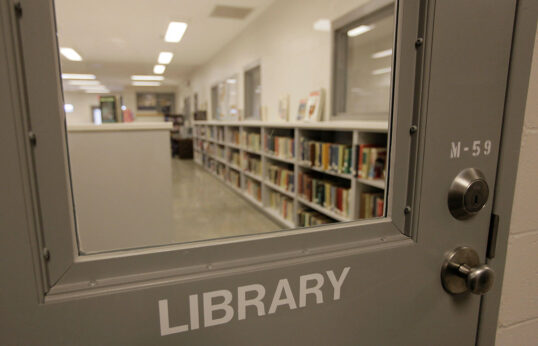

According to Allegheny Councilperson Bethany Hallam, jail “libraries” are nothing like what you would imagine a library being. She speaks with authority, having once been incarcerated herself.

“In our jail, the ‘leisure library’ the administration always references is actually just a couple dozen old books with ripped and missing pages,” she said. Prisoners there used to rely almost solely on volunteers and external organizations for all of their reading needs. Recently the jail system implemented a tablet program, although there’s very limited Wi-Fi access. Hallam stated that incarcerated people can have e-books now, but they’re only allowed to have them from 9 a.m. to 10 p.m., with a 90-minute limit. “After that, you were kicked out of the tablet and charges were imposed,” she said.

Alex Friedman, a former volunteer who ran a program that allowed distribution of books at the Allegheny library, explained what he sees as the real motivation for the tablet program: The point of getting tablets into incarcerated people’s hands, Friedman says, is to be able to sell access to communication like texting or video chat and games that he calls “time-wasters on your phone” that are hyper-monetized. “It’s basically a way to milk people of their commissary funds without selling them any physical goods.” On top of all this, just 214 titles are available on the tablets.

The structure of a prison library varies county to county and state to state. In New York state, librarians in correctional facilities report to the Deputy Superintendent for Programs. One librarian told me on Twitter that a very supportive superintendent made it possible to broaden what was available in the library for underserved populations and to implement film and book discussion programs. Limited by a small purchasing budget, they rely heavily on donations and a robust interlibrary loan program.

“I bought books,” the New York librarian reported. “I bought DVDs. Had multiple newspaper and magazine subscriptions. Plus, for those incarcerated away from home, they could read the hometown paper.”

A librarian at an Omaha facility explained to me that their materials budget—$1,000 a year—is barely enough to maintain what’s being worn out through natural wear and tear. There is some programming, he said, but not enough staffing and not enough time. However, the librarian is available for a lot of hands-on assistance, especially readers’ advisory and general advice. They also operate a law library and have two inmate-clerks whose full-time job is assisting in legal matters.

The Allegheny County, New York state, and Omaha prison libraries described here are public libraries that are operating with public funds. As in all the prison libraries, there is a lot of structure and red tape, but the staff tries to find a way to make it work so they are able to provide service to their clients.

Few books, lots of profits

And then there are the private prison libraries.

Geo Group, a private prison megacorporation, runs a Central Correctional Facility for convicted sex offenders in Arizona. Daria, who didn’t want to share her identity to protect her job, worked as a prison librarian at the then-new facility in 2007.

Typically, materials for a library at any new facility would be selected by a professional librarian trained to research what the particular population to be served would need. Daria was dismayed to find, however, that the starting collection at the facility had been ordered by a Geo Group employee with no training. “It was like a small school library for teenagers,” she said.

Daria reported that she drove to Phoenix to go through warehouses of discarded books to build a collection. “No one in the prison or corporate cared what I did and I had no money,” she told me on Twitter. “I did the best I could trying to build a collection with basically nothing.”

All services in private prisons are bare bones, but library services are at the bare bonesiest. Prison libraries, both public and private, are forced to rely heavily on volunteer organizations, public donations, and other organizations to maintain collections and offer needed services to inmates.

In Ohio, one of the few ways incarcerated people can access books is through JPay accounts on tablets, according to the Books to Prisoners Seattle project. JPay is a for-profit company that contracts with prisons to manage commissary accounts. The facilities’ exclusive-access contracts with JPay mean incarcerated people and their families have no choice but to pay exorbitant fees to the company in order to get tablets for sending emails or accessing reading materials. Books are free, but the selection is reportedly so paltry that eventually users are driven to purchase other content.

The new director of the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction, Annette Chambers-Smith, worked as a financial manager for JPay immediately before being appointed to lead the state’s prison system this year.

The Books to Prison Project reports being unable to send free dictionaries and blank notebooks to some areas because the contract between the prison system and a private commissary vendor stipulates that such items can only be received through commissary purchases.

Paying per minute to read

In West Virginia, under a contract between the state Division of Corrections and Rehabilitation and a company called Global Tel Link, prisoners are now being charged 3¢ per minute to access books that are free to the public through the free digital library Project Gutenberg. “If you pause to think or reflect, that will cost you,” Katy Ryan, Appalachian Prison Book Project’s founder told Reason, a Pittsburgh publication.

According to Newsweek, it costs inmates 5¢ per minute to read books, listen to music, or play games; 25¢ per minute for video visitations; 25¢ per written message; and 50¢ to send a photo with a message. Wages in the state’s prisons range from 4¢ to 58¢ an hour, Prison Policy Initiative estimates.

Profiteering practices in prison facilities are difficult to challenge. The Appalachian Prison Book Project tried to meet with the leadership of the prison system. Leadership made it clear that they saw the charging of inmates for access to content as a positive development and did not intend to change it.

The Books to Prisoners program reported that in Ohio they haven’t been able to gain much traction because of “a lack of on-the-ground organizers who can hold rallies and provide quotes for local reporters.”

Allegheny tells a slightly different story. After local attention and pressure from the public, the Allegheny County Jail announced that they were going to partner with the Carnegie Library system to make more e-books available to prisoners in the jail. It also announced that incarcerated people could once again access books through approved sellers.

Every month, Allegheny Councilperson Hallam introduces a motion to the Council to put $50 on each incarcerated person’s tablet account. “So basically what we’ve decided,” says Hallam, “is if the administration wants to be difficult and keep profiting off of incarcerated folks, we’re going to give those profits right back to the folks who are impacted.” So far, Hallam’s motion has passed every month.

It is in fact the insidious creep of corporations and profiting that is the biggest threat to prison libraries and the incarcerated people who use them. Without action and organizing against this profiteering, that creep will continue.

Correction: When originally published, this article reported that Ohio inmates were only able to access books for a fee on JPay tablets. The text has been updated to reflect further information provided by Books to Prisoners concerning the limitations placed on inmates’ book access.