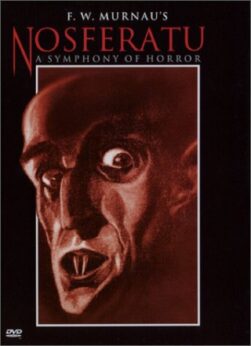

This month marks the 100-year anniversary of the debut of the German Expressionist silent horror film Nosferatu. The unauthorized and unofficial adaptation of Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel Dracula has been regarded as one of the most influential masterpieces of the silent film era. Watching the 80-minute film a century later, it is clear that the movie’s relevance goes beyond the technicalities of filmmaking. Themes in the film, such as politics, plagues, xenophobia, and sexual repression still strike a heavy chord in our current reality. Don’t let the age fool you, this movie still has a relevant bite.

Directed by F.W. Murnau, and screenplay by Henrik Galeen, the story takes place in the fictional German town of Wisborg in 1838. Thomas Hutter (Gustav von Wangenheim) is sent to Transylvania by his employer, estate agent Herr Knock (Alexander Granach), to visit a new client named Count Orlok (Max Schreck) who plans to buy a house across from Hutter’s own home. Danger arises as Thomas realizes something is very wrong with Count Orlok. Yet, his realization may have come too late, as Orlok makes his way to Wisborg, bringing a deadly plague with him. The only hope seems to be with Thomas’s wife Ellen (Greta Schröder), who realizes she may have to make the ultimate sacrifice to save her town.

I have a confession. This year I realized, upon sitting down to watch the film for its hundredth birthday, that I had never actually seen the movie in its entirety. Sure, I have shared and seen plenty of internet gifs and memes depicting scenes from Nosferatu over the years, but sitting down to experience the whole movie hadn’t occurred until this month. And I will admit that if there was any year worth watching it, it would be in the tumultuous time of 2022.

It is a film that haunts you for a variety of reasons. The music score and the directing keep you enthralled with every scene. No dialogue is heard, but every moment is felt. Even in a world of modernized CGI creatures, the classic vampire look of Count Orlok still holds fearsome weight today. Music and shadow create an atmosphere that is just as seducing as the vampire lore the film seeks to detail. All of this is true, but what makes this film seal the deal, and go for the jugular (as vampires are known to do), is the underlying themes that lurk in the very shadows of the horror it presents.

Count Orlok is not the conventionally handsome seducer that we’ve come to know Dracula to be. Yet he is still a representation of sexuality and desire. One could argue that by making him something that is both fascinating and seemingly repulsive to behold, he became a symbol for the repressed desires of the people of that time. He is the alluring taboo, and in the shadows are where he finds his victims. Their shudders, fear, and inevitable surrender play on the things humans may have felt the need to do in secret for fear of it being revealed in the light– particularly when it came to two issues often frowned upon during this time. That being women’s sexual expression and homoeroticism.

There’s a scene where Thomas accidentally cuts his finger while dining with Orlok. The Count sucks the young man’s finger. Thomas recoils, taken off guard by Orlok’s behavior. As he backs away Orlok asks to be in his company for longer. Despite his obvious fear, Thomas relents and sits with the vampire. He falls asleep, waking up with fang marks on his neck that he quickly dismisses as mosquito bites. It’s a brief scene, but a striking one. A point is made that Orlok does the intimate gesture of suckling the neck of both women and men alike.

This allusion to same-sex intimacy is no stranger to vampire tales. Carmilla, the 1872 Gothic novella by Irish author Sheridan Le Fanu, is one of the earliest works of vampire fiction. It came out nearly 25 years before Stoker’s Dracula. Carmilla dealt with a female vampire who preyed upon women. The danger in that story derived from the women victims being seduced by Carmilla’s beauty and power. The Countess represented the forbidden and the arousal she elicited in her prey.

Eroticism like this plays out in Nosferatu as well. This is in 1922. That should be seen as groundbreaking given that famous figures like Irish poet Oscar Wilde were tried (and sentenced) for homosexuality not even 30 years earlier. It should also be noted that director Murnau was said to be gay as well.

Murnau deviates from Stoker’s novel by making it so the true hero, in the end, is Ellen. Even from the beginning of the film, she is more aware of the danger than her oblivious husband. All throughout Nosferatu well-to-do men attempt to figure out what plagues the townsfolk, but each time they come to empty conclusions. It is Ellen, who is often dismissed and coddled, who figures out the true remedy to rid the town of Orlok. She has to take the burden upon herself and make the ultimate sacrifice willingly.

This is a departure from Stoker’s Dracula, where the main female protagonist, Mina, unwillingly falls prey to the vampire’s bite. In Stoker’s story hope is found after Mina gives birth to her son. Mina is made important for her gendered role of childbearing. In Nosferatu, Murnau subverts this by making Ellen the hero solely on her courage and understanding.

Now, I’d be remiss not to mention the debate around anti-Semitic overtones in the film. There have been critics who theorize that Orlok’s long hooked nose, property buying, and other exaggerated features play on caricatures associated with Jewish people during this time. Some argue that Orlok bringing rats with him in the coffins, thus bringing about the plague, is representative of the anti-Semitic prejudice growing in that time that Jews were rat-like people responsible for the suffering of “true” Germans.

I think we’d be doing a disservice to this film to place it in such a black and white framework. Nosferatu was produced in post-World War I, pre-World War II Germany. Adolf Hitler’s Nazi party would come into full power 11 years later in 1933. While there are themes of otherness in the film, I’d argue that it could be seen as a criticism of the anti-Semitic rhetoric growing in Germany at that time.

This becomes glaring in Act Five of the film when it is plainly said that the sick and weary townsfolk look for a scapegoat for their suffering. They find it in the estate agent Herr Knock (played by Jewish actor Alexander Granach). The angry mob goes after his character although he is not the source of their pain. He too is a victim of Orlok, unfortunately, put under his spell to be his servant. This matters not to the people of Wisborg. This could be seen as a parallel to the scapegoating rhetoric the Nazi party used against Jews, homosexuals, African-Germans, and political opponents.

The lead actor, Wangenheim, had been a member of the Communist Party of Germany since 1921. He would later flee Nazi Germany in the 1930s and take refuge in the Soviet Union. Granach too would later flee Germany because of the Nazi regime and anti-Semitism.

All this history and more is present in a silent film from the early 1920s! It’s fascinating stuff, but even more fascinating is how relevant it is to our current world.

A century later and we still have governments and those in power who refuse the autonomy of women and the rights over their own bodies. Right now in the United States, there is a concerted effort by the right wing to turn back the hands of time on a woman’s right to choose to have an abortion. The idea of a woman seeking sexual gratification without the burden of childbirth is an ideal that even in 2022 powerful men cannot fathom. No one listens to the Ellens of the world, and thus they are forced to manage and sacrifice on their own.

Not to mention that there is currently an effort to criminalize the discussion of gay and transgender existence in schools. Vague and dangerous legislation such as the Parental Rights in Education bill, (also known as the “Don’t Say Gay” bill), has now been passed by both the Florida Senate and House at the time of this writing. This bill limits what classrooms can teach about sexual orientation and gender identity. Essentially, it condemns the discussion around sexuality back to the shadows of Nosferatu’s time.

Nosferatu, being an Expressionist film, would later be condemned as “degenerate art” by the Nazi regime. By 1937, the concept of degeneracy was firmly entrenched in Nazi rhetoric and policy. Those identified as degenerate artists were subjected to sanctions that included being dismissed from teaching positions, being forbidden to sell their art, and in some cases being forbidden to produce their work. This idea of censorship of art and expression is not a new one, and unfortunately, it is not a harmless relic from our past.

Culture wars rage on today, as books depicting the experience of people of color, LGBTQ, and other marginalized groups are being banned from school libraries and classrooms. Literal public book burnings are back in “style” under the guise of protecting the (white) youth. Just as the Nazis advocated that “degenerate art” was an “insult to German feeling.”

The horror in Nosferatu bleeds out of the frame into our own reality. It’s a fascinating nightmare that haunts us in the present time. Happy birthday to the vampire film that helped to start it all.

Orlok’s menacing gaze is but a symbol for the issues that we have yet to truly wrangle with from the shadows. A true horror story indeed.

Comments