The eight days between May 2 and May 10, 1963, when thousands of school children in Birmingham, Ala., defied the fire hoses and police dogs of Eugene “Bull” Connor, marked a turning point in the civil rights movement. True, there had been battles before and other battles – and tragedies – were to come. But, just as the 1936 sit-down strike by auto workers in Flint, Mich., set the stage for the massive organizing campaigns of the CIO, Birmingham helped set the stage for the civil rights legislation of the administrations of Presidents John Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson.

The Year of Birmingham began in September 1962 when the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) agreed to launch “Project C,” a campaign of marches, boycotts and sit-ins demanding desegregation of lunch counters, drinking fountains and restrooms; an end to discrimination in hiring and promotion at Birmingham stores; and the formation of a biracial committee to address segregation in schools and city-owned recreational facilities. The campaign also aimed to free any arrested demonstrators.

SCLC dispatched the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. and other members of its national leadership to Birmingham in April 1963 to join the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights, headed by the Rev. Fred Lee Shuttlesworth, in the formal launch of the project.

Shuttlesworth, often described by King as “the most courageous civil rights leader in the South,” says he was “blown into history” on Dec. 25, 1956, when he miraculously survived the Christmas night bombing of his church.

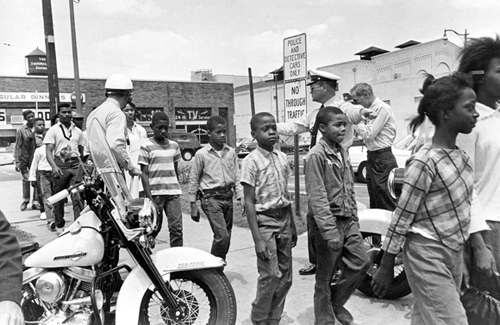

Although it met with limited support, Project C fell short of its primary goal. A month of daily marches and sit-ins had failed to generate support in the Black community or publicity in the national media. Sometime toward the end of April, King and Shuttlesworth recognized the need to change tactics and it was agreed that children would become the foot soldiers of the campaign. Thursday, May 2 was set as “D-Day” where children would demonstrate in violation of the injunction banning them.

Two of Birmingham’s Black disc jockeys volunteered as recruiters for the “Movement,” calling for volunteers to come to a party in a park. “Bring your toothbrushes because lunches will be served,” they said. Earlier a blizzard of leaflets flooded the city’s Black high schools instructing students to leave their classes and report to the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church at noon on May 2.

Sixteen-year-old Cardell Gay, who was arrested three times during those momentous days, was one of those children. “But I only went to jail once,” he said during a telephone interview. “The jails were so full they didn’t have room for any more. They’d load us on a school bus, take us around the corner, tell us to go home, let us out – and we’d go back.”

Gay’s father was one of the men who stood guard over the Shuttlesworth home at night. “He didn’t talk about it but the family understood that it was important for him to leave the house some evenings.”

Claressie Hardy, then 13, spent eight days in detention. “I was arrested on May 2, the day we called D-Day, so I wasn’t there when the dogs attacked us the next day which we called ‘Double D Day.’ But my 12-year-old sister was,” she said proudly. “She was in jail for seven days.”

Over the next week, more than 2,400 youngsters were arrested and nearly 1,000 sentenced to jails. For the first time ever, the Movement had succeeded in “filling the jails.”

Florence Wilson-Davis and her family left Birmingham in 1957, five years prior to these events. She returned some years later. When asked what had changed, she said, “I thought of the things I couldn’t do and the places I couldn’t go when I was a child. The first thing I did when I returned was to go to the library and my son went swimming in the pool at the University of Alabama.”

In her book, Carry Me Home, Diane McWhorter described police chief Bull Connor’s reaction: “The presence of schoolchildren and the size of the demonstration unnerved and perplexed him … Finally Conner called for school buses to transport the protestors. By nightfall more than a thousand young protestors were in custody.”

Up until then the police had refrained from violence. That was to change, and change drastically, a day later when more than 1,000 youngsters again defied Birmingham’s firemen, police, and – this time – K-9 dogs. We turn again to Carry Me Home:

“The firemen kept their fogging nozzles on, misting their human targets as if they were prize flowers. Some marchers backed off. When a dozen flopped down on the sidewalk, the firemen switched on their monitor, fed by two hoses for maximum power. The sound of the hose spray shattered the singing like automatic machine gun fire.

“The children flung their hands to their faces and then embraced, holding their ground for a few seconds before sprawling across the sidewalk. Those trying to flee were pinned against doorways and the group leader took the high-powered spray until the shirt was ripped from his body. The marchers who continued to pour out of the Sixteenth Street Church, were sent skittering down the gutters. One girl surfaced with a bloody nose, another with scratches around her eyes.

“At Connor’s command, six German shepherd police dogs pulled their handlers to the front of the police line. Milton Payne, a 23-year-old African American was bitten in the heel, calf, and thigh. Two dogs jumped Lee Shambry, ripped his pants leg off and bit his arm, leg, and hip. A dog charged at 7-year-old Jennifer Fancher and knocked her down.”

TV cameras and photographers caught much of the action and scenes of Birmingham’s dogs and fire hoses dominated the Friday evening news. The Saturday edition of The New York Times featured a three-column picture of Walter Gadsden fending off one of Connor’s dogs beneath a headline screaming: “Dogs and hoses repulse Negroes at Birmingham.”

Saturday also found Burke Marshall, director of the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice, on an airplane bound for Birmingham.

After the events of Double D-Day, demonstrators and city authorities worked out a truce: Police and firemen would keep their dogs caged and nozzles turned off and demonstrators would peacefully submit to arrest. Although unstated, it was agreed that protests would begin at noon.

That changed on May 7 when hundreds of youngsters, riding in cars driven by Movement Moms, were already sitting at lunch counters in downtown Birmingham even as the clock struck 12:00. Although serious violence was prevented, Movement leaders, unsure of where events might go, suspended demonstrations for 24 hours pending the outcome of negotiations between the Movement and the city’s downtown merchants.

The path of negotiations was strewn with difficulty. Shuttlesworth was not at the table. He was in the hospital, the result of being knocked down a flight of stairs by a stream of water from a high-pressure fire hose.

In their first gambit, merchants demanded to know what “you people want.” (Although the demands had been put forward on April 3, none of Birmingham’s white-owned newspapers had published them. Nor had they been aired by the major broadcast media.)

Another roadblock was the reluctance of the store owners to move against the wishes of the “Big Mules” – the heads of U.S. Steel and Hayes Aircraft, Coca-Cola, the banks, utilities and representatives of the city’s major law firms. “We don’t want to get caught in the middle,” one of them said during the talks.

Negotiations with representatives of an unrepentant power structure were clouded by another problem – the need for a half-million dollars to bail out the children still in jail. Although Henry Belafonte and others had raised substantial amounts of money, the problem was finally resolved when the National Maritime Union, the United Steelworkers and the Auto Workers Union each sent some $40,000 to Birmingham.

Under terms of the settlement, the merchants agreed to desegregate their fitting rooms within three days after the end of demonstrations. Within 30 days of the change in the city administration, they agreed that signs would be removed from restrooms and drinking fountains and that within 60 days the lunch counters would be desegregated. The employment program outlined in the agreement called for “one Black sales person or cashier,” leaving it unclear whether this was for each store.

Shuttlesworth left his hospital bed to lend his less-than-enthusiastic endorsement of the agreement that brought Project C to a conclusion. He opened the press conference by reading from a prepared statement saying Birmingham had “reached an accord with its conscience” and that enough progress had been made toward meeting the Movement’s demands that there was no longer the “necessity for further demonstrations.”

King, however, was much more enthusiastic, hailing the agreement as the “moment of great victory” and counted the whites and the city itself among the victors.

For their part, spokesmen for the power structure responded with a statement beginning, “It is important to understand the steps we have taken were necessary to avoid a dangerous and imminent explosion.” The statement deplored the demonstrations that had brought the agreement about and discouraged recriminations.

Birmingham Mayor Art Hanes called the white negotiators “a bunch of gutless traitors.” Connor, while insisting that the Black community “didn’t gain a thing,” said, “I would have beaten King if those damn merchants … hadn’t given in.”

Whether the merchants had given in or not, the Klan hadn’t. Even as the agreement was being made public, the Klan was planning a rally for May 11. Before daylight on Sunday two bombs would explode, one at Rev. A.D. King’s church and the other at the Black-owned Gaston Motel that had served as headquarters for the Movement.

That afternoon, Ramsey Clark, a Justice Department lawyer, was sitting in the Birmingham airport drafting a memo to Attorney General Robert Kennedy in which he called for federal legislation that would outlaw discrimination in public accommodations and employment.

There was one more chapter – one more senseless act of racist savagery – before Birmingham Summer 1963 would end. That came at 10:22 Sunday morning, Sept. 15 when a bomb exploded at the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, blowing a large hole in the wall of what had been the women’s lounge. Debris – concrete, stone, wood and mortar – that had once been a church wall had been blown against the opposite wall.

And somewhere in the wreckage were the bodies of four young girls: Denise McNair, Cynthia Wesley, Carole Robertson and Addie Mae Collins.

The final chapter of Birmingham summer would not be written until years later when, on May 17, 2000, Bobby Cherry and Tommy Blanton, the last living suspects of the Sixteenth Street Church bombing, were arrested. Both were convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment. Robert Chambliss, considered by many to have been Birmingham’s “master bomber,” was sentenced to life imprisonment in 1977 for his role in the bombing.

* * * * * *

The political economy of Birmingham

From its very beginning in 1871, Birmingham was different from other cities. It was southern and was one of the few places on the globe where quantities of iron ore, coal and limestone can be found in abundance. Thus it had industry – not just any industry, but steel – the stuff that built the nation. And because Birmingham had industry, it had a large concentration of workers who became the special interest of the CIO. This mix gave rise to a tradition of racial unity and organized protest unheard of elsewhere in the South.

Never before had the ruling class claimed racism so crudely and never again would the country’s corporations so boldly foment racial strife, with U. S. Steel setting the example by bankrolling the League to Maintain White Supremacy to spread the white supremacy gospel among its workforce.

The Birmingham Power Structure was probably the most impressive group ever assembled outside a country club – the presidents not just of the big manufacturers but also of the banks, utilities, and partners from the major law firms.

That they were the shakers and makers is best illustrated by the fact that in an effort to get negotiations in Birmingham off dead center, several Kennedy cabinet members made personal phone calls to several of these “Big Mules” urging action.

– Fred Gaboury