This weekend marks a half-century since the first Pride march took place on June 28, 1970. That initial event in New York City, called “Christopher Street Liberation Day,” recalled the Stonewall Rebellion of a year earlier—the night a band of fed-up queers stood up, fought back, and launched a liberation struggle that transformed the world.

With Black and Latina trans sex workers and drag queens in the vanguard, the patrons of the Stonewall—and much of the Christopher Street neighborhood—declared they’d no longer submit to the genital inspections, arrests, and assaults that were regularly meted out by the “Public Morals Squad” of the mafia-corrupted NYPD. The confrontation that started in the bar on June 28, 1969, spilled onto the streets, with battles raging for several nights. The first Pride was, quite literally, a riot—a full-on uprising against police violence and harassment.

It was the end of the 1960s, a tumultuous decade in which the Civil Rights Revolution of Black Americans scored major victories, women demanded equality, wildcat strikes by workers shook the corporate world, anti-colonial struggles swept Africa, Asia, and Latin America, and the small country of Vietnam fought for its survival against the world’s biggest imperialist power. Oppressed peoples were in motion everywhere—the Stonewall Inn was the place where gays joined the fight. Since then, the movement has grown, expanded to become more inclusive, and notched numerous wins.

But up until a few weeks ago, it looked as though the summer of 2020 might be first since 1970 to see no major public commemorations. Most cities and towns have nixed their Pride festivals due to coronavirus fears; corporate pride was canceled. Activists have been reimagining what Pride will look like in response. When COVID-19 scuttled all big events, organizers put together a 24-hour online Global Pride for June 27 to replace the typical floats and extravaganzas that typically take over the streets this weekend. But parade or not, Pride carries on. There is plenty to both protest and celebrate right now, and the current period displays many parallels to past moments in the movement’s history, with lessons that are again being relearned.

Pandemic politics: From HIV/AIDS to COVID-19

When it comes to COVID-19, the absolute incompetence and/or refusal of the federal government under Donald Trump to consistently pursue and execute a plan to contain, and the illness itself, baffles many here at home and around the world. But it’s a familiar story for LGBTQ people. This is a community that has been ravaged by the worst viral pandemic in global history—HIV/AIDS. Medications and treatments have dramatically improved survival rates and quality of life for those infected, and prevention methods have slowed its spread, but this global health crisis has claimed at least 32 million lives and infected up to 75 million people over the past 40 years.

For decades, gay and bisexual men in the United States fought for their lives while the government for too long saw little value in them. Ronald Reagan, the U.S. president at the time the AIDS crisis first exploded, would never even bring himself to mention the disease in public. The persistent fightback of activists in the streets, the work of humane health professionals, and the election of pioneering gay and lesbian political leaders helped force a change.

But also like the coronavirus crisis, HIV/AIDS has always been a pandemic defined by racial disparity. Just as Black people have been among the hardest hit by COVID-19, the same trend prevails for HIV. In almost every demographic group—gay and bisexual men, women, and heterosexual men—it is Black Americans who are most at risk for HIV infection and transmission.

For all these reasons and more, pandemic politics are pushing many LGBTQ organizations to join the fight for universal health care—Medicare For All. People who are LGBTQ still face discriminatory and financial barriers to getting the care they need, whether it be the expensive costs associated with HIV/AIDS medications, hormonal therapy for transgender persons, mental health, or essential services like PrEP that aren’t always covered by private insurance (for those fortunate enough to have insurance).

Pride At Work, the AFL-CIO’s LGBTQ constituency group, has long been on record supporting Medicare For All and is currently one of the leaders of a campaign to block Republican efforts to enact anti-LGBTQ measures under cover of the pandemic. The biggest example of such is Trump’s reversal of Obama-era federal rules earlier this month that banned health care providers and insurance companies from discriminating on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity. Showcasing once more the pettiness and cruelty of this administration, Trump made the change on the fourth anniversary of the massacre at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando in which 49 people were gunned down.

When announcing the reversal, Health and Human Services official Roger Severino bragged that the president was saving hospitals and insurance companies $2.9 billion over five years. Like it always has, discrimination pays for those at the top. But groups like the TransLatin@ Coalition are fighting back; they’re spearheading a lawsuit to halt the move.

All Black Lives Matter

Like the fight for health care access, the national uprising against systemic racism and police violence that’s taken shape under the banner of Black Lives Matter is also injecting fresh energy into the LGBTQ struggle while also forcing gay and lesbian organizations to take a look at their own shortcomings. And like 1969, it is trans women of color that are pushing the change, helping Pride return to its protest roots.

Though the story is not well-known outside LGBTQ activist circles, Pride is a movement that was initiated and led by working-class trans women of color from that very first night at Stonewall. Marsha P. Johnson, a Black trans woman, and Sylvia Rivera, a Latina trans woman, were among those who first resisted police attacks that evening. Johnson, who called herself a “nobody from Nowheresville,” was later credited with throwing the “first shot glass heard around the world” when she fought back at the bar.

She and Rivera were voices for justice against not just the oppressive norms of heterosexual society but also the internal discrimination that pervaded the gay community. Conservative elements within the movement eager to assimilate into the straight world and copy the practices of respectable society tried to sideline those like Johnson and Rivera who didn’t fit the image preferred by the professional classes—gay and straight alike. Like Harry Hay, the Communist who helped launch the fight for gay rights in the 1950s, Johnson and Rivera were radicals who wanted to transform society, not just be allowed to join it. Blocked from speaking at Pride in 1973, Rivera had to steal the microphone and remind the crowd, “If it wasn’t for the drag queen, there would be no gay liberation movement! We’re the front-liners!”

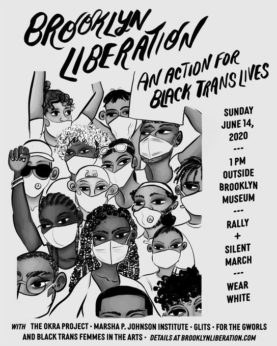

Today in 2020, just like in 1969, Black transgender people are disproportionately the targets of police violence, but demonstrations against brutality can also sometimes put them in further danger, especially when police attack protesters. That’s why two drag queens in Brooklyn—West Dakota and Merrie Cherry—initiated a different kind of rally this month. Evoking the NAACP’s “Silent Parade” of 1917 in which thousands wore all white and marched to protest police violence in New York, they organized the “Brooklyn Liberation” rally on June 14.

A component of the rebellion that has erupted in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, the event put special focus on the violence faced by Black trans women and carried home the message that All Black Lives Matter. Organized in just under two weeks, it mobilized a crowd decked out in white that was 15,000-strong, filling Grand Army Plaza and stretching down Eastern Parkway. Among the speakers was the sister of Layleen Polanco, a trans woman found dead at Rikers Island last year. The words of Melania Brown captured the spirit and message of the march: “Black trans lives matter! My sister’s life mattered! If one goes down, we all go down.”

Actions like the Brooklyn Liberation march are broadening the demands of the BLM movement while also forcing traditionally white-dominated, professional-class LGBTQ political groups to re-examine the exclusion that has plagued them for far too long. It’s the kind of development that would certainly make Marsha and Sylvia proud. As Johnson said, “No pride for some of us unless there is liberation for all of us.”

Celebrating victories and moving ahead

The injustices of COVID and police violence have provided plenty to protest, but this month has also seen victories worth marking. June is often Supreme Court decision season, and some major wins have been recorded lately during Pride Month. In 2015, the movement celebrated when justices made marriage equality the law of the land. But the ruling that came down less than two weeks ago, on June 15, promises to be even more transformational.

The injustices of COVID and police violence have provided plenty to protest, but this month has also seen victories worth marking. June is often Supreme Court decision season, and some major wins have been recorded lately during Pride Month. In 2015, the movement celebrated when justices made marriage equality the law of the land. But the ruling that came down less than two weeks ago, on June 15, promises to be even more transformational.

By a vote of 6 to 3, the Court finally said that LGBTQ people cannot be discriminated against on the job. Protecting LGBTQ persons from discriminatory hiring, firing, benefits exclusions, and salary decisions is a change that will affect millions of people throughout their working life. SCOTUS based its decision on an expansive reading of what it meant to treat someone unequally on the basis of “sex,” the term used in existing federal anti-discrimination laws that cover workplaces. The majority decision said that sex is a broad term which includes sexual orientation and gender identity, even if those categories are not specifically mentioned in law.

LGBTQ organizations have been making the same case for years, but never gotten very far. That’s all about to change. The revolutionary potential of this ruling becomes apparent when extended to other areas of law dealing with discrimination based on sex—the path is now open for groundbreaking change under the Fair Housing Act, the Equal Pay Act, Title IX in education, and more. It will take more legal cases to get there probably, but this decision sets the precedent for including LGBTQ people under all these other protective measures. And to make it even sweeter, it was Donald Trump’s conservative Justice Neal Gorsuch who actually wrote the opinion, pissing off the president—a fitting gift for Pride.

The LGBTQ movement heads into the closing weekend of Pride month stronger than it started out. Driven by anger over the coronavirus pandemic still stalking the country and now pushed along by the national uprising for Black Lives, the LGBTQ struggle for justice and equality continues to advance. It is learning again the lessons taught by some of its own pioneers, remembering that an injury to one is an injury to all. In the words of the Chicago chapter of the Gay Liberation Front in the 1970s, the movement is once more realizing that “our own liberation is inextricably bound to the liberation of all oppressed people.”