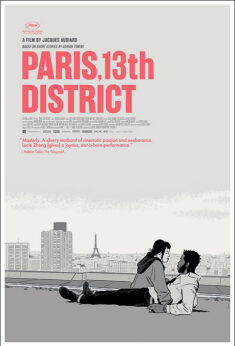

Like other nationalities, Hollywood has manufactured cinematic stereotypes of the French. Unlike Tinseltown movies such as 1951’s An American in Paris, 1954’s The Last Time I Saw Paris, 1964’s Audrey Hepburn-William Holden comedy Paris When It Sizzles, and 1972’s Last Tango in Paris, there are no berets, brioches, baguettes, accordions or on-location (or B unit) shots of urban landmarks such as the Eiffel Tower or Montmartre’s Sacré-Coeur Basilica to be found in Parisian Jacques Audiard’s Paris, 13th District. Indeed, the long shots of this arrondissement (district) on the Seine’s left bank consist mostly of hideous high rises, hardly the charming architecture often associated with the City of Lights.

Not only are there no Gene Kelly-like Americans in Audiard’s contemporary Paris, but apparently there are no “Parisians”—and by that, I mean in the sense that none of the main characters are indigenous inhabitants of France’s capital whose ancestral roots can be traced back generations to Paris. Camille Germain is portrayed by Black actor Makita Samba, who was reportedly born in Paris; and Émilie Wong, played with angsty zest by Lucie Zhang, who was actually born in the 13th district and moved to France from China, is identified onscreen as being of Chinese ancestry. Lest, and reader thinks, I’m making some kind of racial point here, I hasten to add that even the Caucasian character, Nora Legier (Paris-born Noémie Merlant, who co-starred in 2019’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire), is not Parisian. She is a newcomer who has moved at age 33-ish from Bordeaux to Paris to study law at the Sorbonne.

Not only are there no Gene Kelly-like Americans in Audiard’s contemporary Paris, but apparently there are no “Parisians”—and by that, I mean in the sense that none of the main characters are indigenous inhabitants of France’s capital whose ancestral roots can be traced back generations to Paris. Camille Germain is portrayed by Black actor Makita Samba, who was reportedly born in Paris; and Émilie Wong, played with angsty zest by Lucie Zhang, who was actually born in the 13th district and moved to France from China, is identified onscreen as being of Chinese ancestry. Lest, and reader thinks, I’m making some kind of racial point here, I hasten to add that even the Caucasian character, Nora Legier (Paris-born Noémie Merlant, who co-starred in 2019’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire), is not Parisian. She is a newcomer who has moved at age 33-ish from Bordeaux to Paris to study law at the Sorbonne.

If Audiard and his co-writers Céline Sciamma and Léa Mysius have deliberately set out to upset our preconceived images of “Paris” with a contemporary, realistic picture of a Parisian neighborhood, there is one stereotype of the French that the 70-year-old Audiard perpetuates, with relish: That Paris is the City of Love. Indeed, his French characters are so amorous that they would make even the romantic cartoon skunk Pepé Le Pew blush. This big screen adaptation of American cartoonist Adrian Tomine’s graphic novel is quite graphic in terms of nudity and sexuality.

Paris, 13th District is essentially about the interlinked sex lives of reasonably attractive 20- and 30-somethings linked to the eponymous neighborhood. In French, this 105-minute film is entitled Les Olympiades, which I had imagined was a reference to the characters’/actors’ bodies and Olympic-quality lovemaking abilities and techniques, but it turns out “Les Olympiades” actually refers to the residential towers of the 13th arrondissement.

By contemporary Hollywood standards, Audiard’s movie is so sexually explicit that one wonders: If Pepé Le Pew was recently canceled, what will Americans make of the naked, lustful characters and their interplay in this French film? In comparison, actors in U.S. productions often “perform” onscreen sex acts beneath the covers and with private parts covered up, and the openness of their French counterparts makes Americans with their prudish hang-ups about nudity and sexuality look like puritanical, backward imbeciles.

But then again, although Émilie, Nora, and, as I recall, Stéphanie (a teacher portrayed by Océane Caïraty, who offscreen is a professional soccer player) are given the “full Monty” treatment, genitalia of the male of the species are never glimpsed onscreen in the film. Even a dick pic on Émilie’s cellphone appears to be blurred—what’s up with that? Maybe the 70-ish Audiard isn’t as outré as he supposes himself to be?

The stories are interrelated largely through Camille, who has sex with Émilie, Nora, and Stéphanie, though not at the same time (even though Émilie suggests a threesome to Camille when Stéphanie visits). The most interesting plot points revolve around Nora. Mistaken identity is found in ancient Greek theater, Shakespeare, Beaumarchais, and Molière, but in Paris, 13th District this old chestnut is given a decidedly 21st-century cybersex twist that has a huge impact on Nora. She is a sexually conflicted character, who says she had a longtime affair with her married uncle (related through said marriage) and is dysfunctional when engaging in sex, including anal, with Camille. It is said that everyone has a doppelganger (played by Jehnny Beth as cam girl Amber Sweet), and when Nora seeks out hers, the revelation is that perhaps Nora wasn’t enjoying sex because she was having it with what is, for her, the wrong gender. Like the painter she played in the acclaimed Portrait of a Lady on Fire, Merlant’s character again seems to prefer same-sex relationships. Gay Paree anyone?

The lusty Émilie seems conflicted, too, but in a different way. She’s apparently promiscuous, yet yearns for a relationship that combines the sensuous with the spiritual and psychological. The same may be true of Camille: will they find that true love, mixing the physical, mental, and soulful with one another?

Paris, 13th District has at least two poetic scenes, both depicting Émilie in the throes of sexual ecstasy. In one she is seen from above, as if the camera is in the missionary position, atop her. In the other, Émilie fantasizes about ecstatically dancing through a restaurant she works at after a tryst that may or may not also have been merely a fantasy. In any case, these vignettes capture exactly how the sex partner of a lucky lover is made to feel.

Camille’s younger sister Éponine (Camille Léon-Fucien plays the stuttering standup comic whose speech impediment disappears when she performs comedy) points out that she has the same first name as a character in Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables. Indeed, all the leads have literary-related names: Although he’s male, Camille is likely a reference to the female lover in Alexandre Dumas’s novel La Dame aux Camélias and Giuseppe Verdi’s operatic adaptation of it, La Traviata. Nora may refer to the wife of James Joyce, author of Ulysses, while Émilie may be meant to conjure up the Brontë sister who wrote Wuthering Heights, or possibly it’s the female version of Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s treatise Émile, or On Education. But who knows for sure?

The gifted Audiard previously directed 2009’s hard-hitting prison/crime drama The Prophet, which won the Cannes Festival’s Jury Prize and was Oscar-nommed for Best Foreign Language Film. His 2012 Rust and Bone was a wonderfully sexy film about a disabled woman still yearning for romance, which earned Marion Cotillard a nomination for the Screen Actors Guild’s Outstanding Performance by a Female Actor in a Leading Role award.

With the brief exception of one scene, Audiard’s film is shot in black and white, which is just as well, considering the extraordinary ugly, soulless architecture of the 13th arrondissement, utterly devoid of class and charm. If the Reign of Terror ever makes a comeback, I’d like to be the agent for the architects of those despicable-looking towers. To tell you the truth, although I enjoyed Paris, 13th District, I prefer that Paris portrayed by Gene Kelly and Leslie Caron and Van Johnson and Elizabeth Taylor in The Last Time I Saw Paris, which adapts an F. Scott Fitzgerald short story, and Ernest Hemingway’s delightful A Moveable Feast. Last Tango anyone?

I’ve visited Paris several times, but guess I’ll have to wait until October for my next dose of French culture, when I fly to French Polynesia for a travel writing stint aboard the cargo-cruiser Aranui, for a voyage from Tahiti to Pitcairn Island.

Paris, 13th District opens in select theaters and on demand on April 15. The trailer can be viewed here.