Once again, the distinguished late historian Philip S. Foner takes his readers on an intensive whirlwind study tour of the United States, back in time and across the land. Although in this new Volume 11 of his monumental history of the American labor movement his time frame is but three years, 1929 to 1932, this is a pivotal moment indeed. The year 1929, as every student of American history knows, marked the official onset of the Great Depression which sent the worldwide capitalist economy into a tailspin from which only wartime production a decade later would offer relief.

Working people and radicals looked across the oceans—east across the Atlantic and west across the Pacific—to the largest single nation on the planet, the newly created Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), to see if communism was working there. From what they were able to see, apparently it was. The Soviets were calling for trained engineers and agronomists to come work.

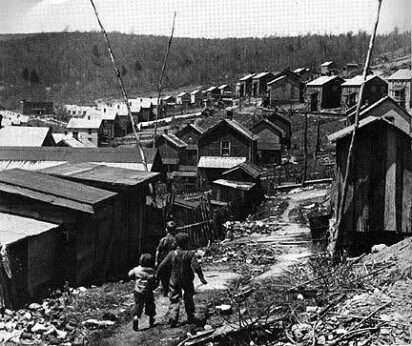

All over the U.S. the Depression sank in, lowering living standards, throwing people to the gutter, literally starving them into submission as the authorities twiddled their thumbs.

Foner shows how hard a road it was to achieve unemployment insurance. The AFL opposed it, not wanting to portray the proud American worker as “on the dole.” He brings us into mining areas, food packing sites, the tobacco fields, auto plants, the ports with their maritime workers, and the rural agricultural industries. Back in the big cities, he opens the door to the sweatshops where apparel workers and furriers bent their backs over their cutting, stitching, and dyeing machines.

One of the strengths of his writing is the attention Foner gives to women workers and Black workers, the most poorly paid, the most likely to suffer the worst effects of the economic decline. “I am a Negro working woman who has done all kinds of work, the dirtiest and the hardest,” he quotes one respondent. “But when times got hard the boss told me I would have to hunt me a job. White women were ready to do the work. I walked from house to house, begging for something to do and could not even find washing or scrubbing.”

From time to time Foner will introduce a song that came out of the period, such as the famous “Which Side Are You On?” by Florence Reece, or “The Soup Song” penned by labor lawyer Maurice Sugar.

Although millions suffered, and Foner does not shirk from describing their pain, he doesn’t exploit their stories for maudlin effect. They serve, rather, to point up how urgent was the task for the working class to organize into a force powerful enough to reverse conditions and get the production lines moving again.

If anything, this crisis—as crises tend to do—brought into sharp focus just what kind of country the U.S.A. really was. Black historians and writers have asserted that across wide swaths of the South, African Americans lived under what could just as well be called fascism, with no rights the white man needed to respect. In many respects, the North and West weren’t much better. If you lived in Harlan County, Kentucky, and were forced to rent a shack from the mine owner and buy all your goods from the company store with scrip, whatever your color, you might have called it a form of modern feudalism. Mexican-American workers in Imperial County, California, fared no better. Police forces, state militias, and federal armies were often deployed against ordinary workers legally organizing for their rights, or marching to call attention to widespread hunger across the nation. Such examples must have been an enlightening inspiration to fascists and dictators abroad—Portugal, Italy, Germany, Spain—showing them just how much exploitation and violence the overseers of an advanced industrial society could get away with.

As far back as 1919, less than two years after the Russian Revolution, El Internacional, the organ of the Spanish-speaking (mainly Cuban) cigar workers in Florida, editorialized that “in the United States a capitalistic government is making the working class behave, and we call that ‘Maintaining Law and Order.’ In Russia, a working-class government is making the capitalists behave, and we call that a ‘Reign of Terror.’”

Faulting the AFL

Foner exposes how the AFL, which effectively only purported to serve white male workers in isolated crafts—there could be a dozen or more small unions in a single factory—month after month, year after year, not only misconstrued the signs of supposed prosperity during the Roaring Twenties, but then failed to grasp the seriousness and severity of the economic crisis after the stock market crash in October 1929. With a growing, sickening sense not just of incompetence, but of privilege, out-of-touch alienation and uncaring, we watch a sorry parade go by—labor conventions beaming with optimism and bristling with anti-communism, class collaboration as if there truly were no other way to slice the cake, fulsome paeans to the strength and nobility of the American capitalist system and to the leadership of President Herbert Hoover.

Against this background, Foner poses the fightback spiritedness of the Communists, their party barely a decade old at the time, yet brimming with pipe dreams of a USSA working in concert alongside the new USSR. The author acknowledges the ideological influence of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW, or Wobblies), founded in 1905 along anarcho-syndicalist lines, who saw nothing in common between the working class and the owning class, and who also tenaciously reached out to Black workers, young workers, agricultural and lumber workers, women workers, whom the AFL had never bothered with. Many of the early leading Communists had cut their teeth amongst the Wobblies. If their steel was tempered in those earlier 20th-century struggles, it was now organized into a militant party based on the Soviet model that had conquered Tsarist Russia.

A constellation of new unions grew together into the Trade Union Unity League (TUUL), which in turn grew out of the Trade Union Educational League, the subject of Foner’s Volume 9. The TUUL is not widely recalled today, but it should be, and this is your best source for it. Though short-lived, it established the template for the fighting unions that formed the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) in the mid-Thirties. The CIO, as even beginning students of labor history know, organized along an industry-wide principle rather than specialized crafts that was the AFL approach. This principle drew on the One Big Union idea developed by the IWW.

The Ford Hunger March of 1932 was one especially dramatic crime the capitalists never paid for—hundreds of peaceful, unarmed demonstrators at the Ford auto plant were fired upon in cold blood, with five young martyrs losing their lives.

A very exciting chapter is the one about how the Communist-dominated fur workers’ union fought back against the Lepke-Gurrah Racket, at great personal cost, at a time when centrist, and even nominally socialist unions and civic organizations considered it the better part of wisdom to cave in to it. Foner sets the scene dramatically, with armed gangsters raiding the union headquarters, bullets flying, brave secretaries on the ground floor phoning a warning up to the offices on the higher floors, the investigations, the testimonies, the indictments; and the total lack of credit given—even when the film version came out—to the Communists who stopped the Mob in the apparel industry, well, at least for a while. A talented playwright could do wonders with this story.

As each chapter unfolds—organizing in various economic sectors and geographical regions—Foner highlights the successes, alongside the inexperience of the Communist Party. A reader might tire of seeing almost every struggle, rally, campaign or march reported so fully in the Daily Worker. Could a historian of another ideological turn have written these stories with other eyes, other sources? One would have to be a scholar in this field to fairly answer that question, but from the wide-ranging sources Foner consults, including union publications, mainstream press, archival holdings, government reports, academic dissertations, and other treatments of the period, the inescapable conclusion is that no, really no other single party or movement had the passion and dedication to frame the issues, devise the institutions and strategies, and provide the leadership that the moment demanded.

At the same time, Foner was able to examine the Communist Party during this critical period; and while singing its praises, he also points to ideological constraints imposed on it by the Comintern (or self-imposed, if you will) in this radical “Third Period.” The über-revolutionary stance the party assumed in the late Twenties and early Thirties seemed bold as a counterforce against the sclerotic AFL, yet in its bashing of socialists and progressives who did not share the total CP line, also alienated millions who might have been attracted to an earlier application of the United Front strategy. Still, as Foner suggests, the TUUL was the great forerunner to what has so far been the most exciting and productive era in U.S. labor history.

As the very last paragraph of the book, Foner writes, “As we shall see in our next volume, the Communist Party was soon to shed its sectarian policy and would present both an outlook and a program that would generate much wide support from the people of the United States.”

And in those words, he summed up his great life’s work, the ten volumes of the History of the Labor Movement in the United States that he published during his lifetime, this final 11th volume that he left in his posthumous papers and that has now been brought to light (thanks to some persevering volunteers led by Prof. Roger Keeran), and a glance forward to the work yet to be finished.

Life took its course, and people learned. Having absorbed their lessons from the unsung TUUL in the 1929-32 period, the builders of the mighty CIO waited just over the horizon, ready to spring into action once the tethers of government had been loosened with the election of Franklin D. Roosevelt and a Democratic Congress in 1932.

A fine and exhilarating read!

Philip S. Foner

History of the Labor Movement in the United States, Volume XI: The Great Depression, 1929-1932

New York: International Publishers, 2022

242 pp., $19.99

ISBN: 9780717808670.