NEW ORLEANS — New Orleans Opera (NOO) promoted its production of Blue as “the southern premiere of the most talked-about new American opera.” I’d been meaning to get back to the Crescent City to see it once more after leaving it in 1978 (45 years ago!) when I finished up my last degree at Tulane. I’d read about Blue in musical publications and was eager to see it. It features the Tony Award-winning Jeanine Tesori’s score, and I adore her work—Fun Home, Shrek the Musical, Soft Power, Violet, Caroline, or Change. The libretto (his first) is by NAACP Theatre Award-winning playwright and director Tazewell Thompson. So I scheduled my trip to include the Nov. 10 date at the Mahalia Jackson Theater, at Louis Armstrong Park just outside the French Quarter, a new venue which didn’t exist in the days, as a student, that I attended the opera in New Orleans.

North/today/city

Inspired by recent events and by two classics of Black literature, Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me and James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time, Blue premiered in 2019 at the Glimmerglass Festival and has since been staged by a number of other companies in the U.S. and abroad. It was named the Best New Opera in 2020 by the Music Critics Association of North America. The New York Times listed Blue as Best in Classical Music for 2019. Along with Missy Mazzoli, Tesori is one of the first female composers commissioned by the Metropolitan Opera. Her opera Grounded, with a libretto by George Brant based on his play, is scheduled to premiere at the Washington National Opera in 2023, followed by a Met premiere in 2025.

Although the NOO production was presented in a large theatrical house, Blue itself is a work that can be staged in much smaller venues as well. In fact, NOO offered it as part of its Ranney and Emel Songu Mize Chamber Opera Series, building its own sets, with the Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Michael Ellis Ingram and directed by Timothy Douglas. It runs 2:15 hours plus one intermission.

To summarize the plot briefly, a Black couple anticipates the arrival of their first child. While pregnant, The Mother (Krysty Swann), a Harlem restaurant owner, commiserates with her three “sisters” (Chabrelle D. Williams, Kourtney J. Holmes, Kendra Faith Beasley) about their fears for the future of this baby boy. After their son arrives, The Father (Cory McGee), an NYPD cop—or “officer of the law,” as he prefers—is warmly congratulated by his fellow officers (Tyrone Chambers II, Mark-Anthony Thomas, Ivan Griffin) who, in between drinks and scores in a football game, prepare him for the sleepless nights in his immediate future and reassure him that even as a badly paid rookie, if he stays with the force he’ll be “covered for life.”

Sixteen years later, The Son (Jonathan Pierce Rhodes) is now a young artist and activist with an eye on art school. “Woke” to structural racism and economic pressures, he clashes with his father, practically accusing him of being exploited by the white system to oppress his own people in the ’hood. The Son, who’s already been apprehended for turnstile jumping, painting graffiti, and spitting in a cop’s face, is fearless about going out to protest, while The Father, out of love for his only child, knowingly counsels him to be more careful: “You grown when I say you grown.” An embrace at the end of Act 1 shows that The Son will follow his own heart, but understands and accepts his Daddy’s love.

Act 2 begins after The Son has been killed by a white cop at a protest. The Father seeks counsel from a Reverend (Gordon Hawkins), chafing at the pastor’s passive bromides about acceptance and forgiveness. He has come to see that religion itself is but another pillar in the edifice that keeps white supremacy going. His fellow police officers, and The Mother’s women friends and church congregants, grieve The Son’s killing—one more Black boy slain at the hands of police. A degree of solace is found at the funeral as they imagine The Son sleeping forever in his own room in God’s heaven, but the senseless, racist murder will always loom over his parents’ and the community’s lives. The final scene shows a flashback of the family gathered over the dinner table, where The Mother has prepared a special menu to accommodate The Son’s veganism. The Son assures his Daddy that the demonstration he’s headed out for will be peaceful and silent—in fact, he suggests his father could join him.

The characters have no names, only titles, so that the audience may grasp the sad universality of this story. In Thompson’s original conceit, The Father was a jazz musician, like the librettist’s own father, but accepted Tesori’s suggestion that The Father instead be a police officer, heightening the irony and poignancy of the narrative.

As part of its community outreach, NOO organized a mural for Blue created by 10th and 11th-grade art students taught by Roan Smith, studying the plot and characters of the opera, as well as the art of Harlem Renaissance artist Charles Alston. They adapted Alston’s paintings “Walking” and “Cityscapes of Harlem,” and came up with a design featuring peaceful protest, titling the mural “Shades of Blue,” on view at the opera.

As part of its community outreach, NOO organized a mural for Blue created by 10th and 11th-grade art students taught by Roan Smith, studying the plot and characters of the opera, as well as the art of Harlem Renaissance artist Charles Alston. They adapted Alston’s paintings “Walking” and “Cityscapes of Harlem,” and came up with a design featuring peaceful protest, titling the mural “Shades of Blue,” on view at the opera.

Tony Cisek provided the scenic design; Kara Harmon the costume design; Peter Maradudin the lighting designer; and Phoenix Rose the wig and makeup design.

Authors Ta-Nehisi Coates and James Baldwin are declared atheists, a stance that clearly affects the eventual opera inspired by their writing. The libretto acknowledges the powerful role played by the church in African-American life, alongside family, community, and food, but the implication is clear that leaving all of life’s troubling questions in the hands of an invisible god is a far from satisfying response to American racism. The Father goes on an extended rant against the “white god” the “happy, happy Negroes” worship. No wonder that younger people of all backgrounds are leaving organized religion in ever-increasing numbers.

Many strong and lovely scenes dot Blue’s two acts, with a variety of musical styles to fit—where her girlfriends kid The Mother about her sexy new boyfriend and his size-16 shoes, and when they offer her their wishes; where she rhapsodizes about having waited for someone like him to love her; where The Father, at the maternity ward, holds a baby, his son, for the first time, and in that clinical setting calls his boy “a black exclamation point on white linen paper”; where Father and Son argue their viewpoints and share “the talk” about what a Black kid as an “endangered species” needs to remember out in public; the confrontation with the Reverend, where The Father has to admit his boy was shot by “one of my brothers in blue” and declares, “I ain’t gonna study war no more”; the moment the community recites all those cities where the uniformed “great white hunter” has declared open season on Black people; where the funeral assemblage wails and keens about a people “wounded, bruised, and brought low”; a family “festivity of food made with love…for my boys” that immediately precedes, like the Last Supper, the tragedy that will soon follow.

See Tazewell Thompson speaking about his opera in relation to a Dutch production in 2022.

Here is a brief interview with stage director Timothy Douglas about his work on Blue:

NOO presented Blue for two performances only, but my advice to readers is to go see it if it appears on the operatic roster anytime near you. The remainder of the NOO season includes Lisette!, a one-night (Dec. 1) recital featuring Lisette Oropesa, a New Orleans native and world-renowned lyric soprano; and Lucia di Lammermoor on March 22 and 24.

South/yesterday/plantation

While a student, and an SDS activist, at Tulane in the late 1960s and early ’70s, it never occurred to me to visit any of the old plantations that fully occupied the terrain on both sides of the alluvial Mississippi River plain between New Orleans and Baton Rouge. I surely must have thought that was entirely too “touristy” a thing to do. Acknowledging that I’ve already forgotten more than I once knew, I believe it’s accurate to say that if I were asked, as a graduate student in history, just what cash crops they raised on those plantations just a few miles upstream from where I was studying, I might have answered an automatic “Cotton!” And I would have been wrong. The entire economy of that land was tied to slave labor on sugar cane. Any other cultivation—vegetables, fruit, animal products—would have been purely for domestic consumption.

My partner did most of the research on this: Which of the plantations that offered visitor tours featured the most honest treatment of slavery, absent glorification of the romantic Old South? We came up with the Whitney Plantation and booked a tour. But on the bus out of town, carrying a dozen or more visitors from around the country, our driver Brian announced he had just been informed that Whitney had just experienced a water emergency and would be closed until noon. Our next-best option, the Laura Plantation in Vacherie, St. James Parish, was open, and we chose that over Oak Alley, perhaps the best-known of them all for its mansion’s dramatic placement at the end of a stately row lined by magnificent live oaks hanging with Spanish moss.

Our guide at Laura was the articulate, historically adept Pamela Burke, with her sly observations about then and now, and her revelations about the generations of family life at this site. The mansion is lovingly restored, each room filled with appropriate period pieces. She cautioned us to be wary of the term “original,” however. The main house itself had been added to, redesigned, repaired, restored, rebuilt, repainted, and updated, in almost every decade of its existence. Floods, storms, pests, bugs, rot, all took their toll in this semi-tropical climate. Almost none of the furnishings we see today actually belonged to the family. And to accommodate visitors, the house has also undergone substantial improvement to conform to modern building codes. We cannot forget, either, that Union ships fired cannons onto these mansions from their ships on the river, just a spit-distance away, and that Union soldiers marauded through these homes as the enslaved population fled—or joined up with the Union Army.

Dating from the beginning of the 1800s, when this land was still owned by France, the property was owned by “Creoles,” a word with multiple shifting definitions. In the day, it meant American-born, French-speaking, and Catholic, without reference to race! Everyone spoke French here, owners and slaves alike. Mostly Pam emphasized the constant communication with France—suitors and marriages, young men sent off to military college in Bordeaux, Frenchmen moving to Louisiana, Creoles relocating to France. Only later did it occur to me that she didn’t mention the Acadians, French speakers from Eastern Canada, who fled from the British and moved to French Louisiana, lending their identity to the locally evolving “Cajun” culture.

These plantation homes were not, however, showcases for elegance. No crystal chandeliers, no expensive rugs, no marble floors—in fact, stone of any kind really doesn’t exist here, except if imported. These were essentially working farmhouses. The owners oversaw a population of agricultural laborers and sugar-makers for ten months of the year. Only from more or less Christmas to Mardi Gras did the pace slow down and they could escape to their townhouses in the Vieux Carré—today’s French Quarter—in New Orleans. There they could entertain lavishly and show off their wealth to the large community of foreigners who lived there as merchants, and meet potential marriage partners, business associates, investors, and enjoy the delights of the city.

Fortunately, records for this property, and for other similar plantations, do exist. In this case, Laura Locoul, for whom the estate is named, lived for over a hundred years—from the presidency of Abraham Lincoln to that of John F. Kennedy—and wrote an extensive memoir of her life, which has been elegantly published in a beautifully illustrated edition. Documentation also survives in the form of deeds, contracts, tax rolls, sales receipts, marriage certificates, birth and baptismal records for both Blacks and whites, and in the bones of the buildings themselves—the designs, materials, and techniques employed. Many of the imported slaves had been captured from Senegal or other areas where classes of skilled laborers—masons, carpenters, roofers—already had highly developed talents. In Louisiana their expertise was put to work in brick-making, timber harvesting and cutting (those sturdy cypress trees of the local swamps), measuring and fitting with mortise and tenon joints that gave almost indestructible stability to these American-designed structures without the use of a single nail.

Fortunately, records for this property, and for other similar plantations, do exist. In this case, Laura Locoul, for whom the estate is named, lived for over a hundred years—from the presidency of Abraham Lincoln to that of John F. Kennedy—and wrote an extensive memoir of her life, which has been elegantly published in a beautifully illustrated edition. Documentation also survives in the form of deeds, contracts, tax rolls, sales receipts, marriage certificates, birth and baptismal records for both Blacks and whites, and in the bones of the buildings themselves—the designs, materials, and techniques employed. Many of the imported slaves had been captured from Senegal or other areas where classes of skilled laborers—masons, carpenters, roofers—already had highly developed talents. In Louisiana their expertise was put to work in brick-making, timber harvesting and cutting (those sturdy cypress trees of the local swamps), measuring and fitting with mortise and tenon joints that gave almost indestructible stability to these American-designed structures without the use of a single nail.

The principal and highly profitable crop was sugar—although initially, it had been indigo, the plant from which blue dye is derived, but that plant soon succumbed to blight. Enormous iron vats still exist on the property where, in successive stages of purification, the raw cane was pounded and pulverized, boiled and reduced to brown sugar and its by-product molasses, and sold to market (refined white sugar granules came later). To this day, sugar is still the dominant crop here. Along the road, one could see trucks coming and going to the major refineries—Domino, for one. And one could see distant plumes of smoke rising from fields where remains of the harvested cane are being burned off to prepare the soil for new planting.

The labor of a couple of hundred slaves over the period of weeks that was once performed at Laura can now, with mechanization, be performed in a matter of hours. Yet in the day, even after Emancipation, Pam informed us, up to 70 or even 80% of the former slaves returned to the plantation. The promise of “40 acres” never materialized, and without any other safe and familiar place to go, they came back to their old “families.” The Great Migration northward, toward the industrial cities of the Midwest and elsewhere, would start only around the World War I era.

Even in slave times, most lived in shacks adjacent to the fields they cultivated, but a few lived in the mansion as house servants in intimate relationships with their “owners.” “Integration,” Pam intoned, with transparent relevance to times both past and present, “does not mean equality.” The house servants knew all the secrets of the family: Genealogical charts vividly illustrate that Black and white children in and around the house were often brothers and sisters from the same father. The same family names crop up for Black and white alike.

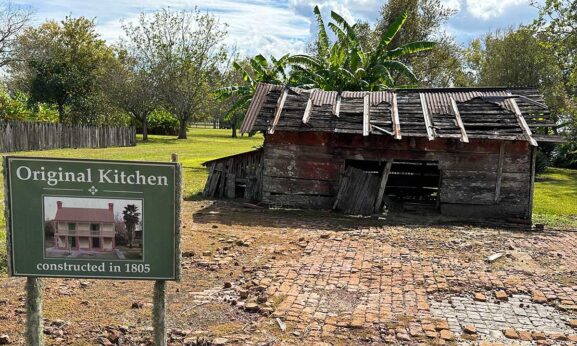

The enslaved population seems to have peaked at about 200 as the Civil War approached. A few of their probable 60 or so wooden shacks survive, as well as remains of the outdoor kitchen a few steps down from the rear of the main house, and a laundry shack. Incalcitrant slaves, Pam reminded us, would be branded; many could be identified by their markings. On one plantation nearby, a mass escape of slaves into the surrounding swampland ended when they were all rounded up with the help of search dogs, brought back to the plantation, summarily killed, every one, and their heads raised onto tall pikes along the elevated levee for all to see as a warning. Life expectancy for Black people on the plantation was 31 for men and 27 for women—many died in childbirth.

Though sugar remains here, the old family domains hardly exist anymore. Most of the land has changed hands, some of it corporate-owned. In the instance of the Laura plantation, shrewd legal maneuvers kept the land intact and even expanded. In most of the other plantations, Louisiana inheritance law dictated that all legal heirs be granted a share of the estate, meaning that sons and daughters alike inherited slices of acreage, and eventually, within a generation or two, the integrity and viability of the plantation as an economic entity had evaporated. Deriving from Napoleonic law, this provision was unique among all the U.S. states. Laura is now listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places, used to interpret history and for heritage tourism.

In today’s news, this strip between New Orleans and Baton Rouge is no longer known for its sugar economy. Nowadays people call it “Cancer Alley,” owing to the proliferation of petrochemical facilities all up and down the river and elsewhere in southern Louisiana. Not only people working in the industry itself, but everyone living downwind of it is subject to some of the highest incidences of cancer in the country. Conversion to a green economy cannot come too soon for folks living here.

The Laura Plantation website can be accessed here.

Yesterday/today, North/South, urban/rural: Race discrimination in America has changed some of its methods, but remains fully intact. So too, in various forms and expressions, does the resistance.