NEW HAVEN and HARTFORD — I’m datelining this review (even though I’ve lived in Los Angeles for the past 34 years) with Connecticut place names because I’m a Connecticut native who left New Haven at 21, returned at the age of 27 to take a teaching job in Manchester (near Hartford) and, after I took up residence elsewhere from 1978 on, made many subsequent visits to family and friends virtually every year of my life.

So I felt on familiar ground reading Radical Connecticut: People’s History In The Constitution State. Some of this history I already knew, though not in so much detail as presented here, and quite a bit more of it I did not know at all, or never would have thought to include in such a volume. I was even a part of some of these events and movements in my day. We are grateful to authors Steve Thornton and his collaborator Andy Piascik for their perseverance in tracking down these people and movements that reflect on my native state.

One guy I learned about in this book is Thomas Skidmore (1790-1832), a “forgotten revolutionary” from Fairfield County, a disciple of British thinkers Mary Wollstonecraft and William Godwin. According to Piascik, “Skidmore was appalled by the twin holocausts of U.S. history: the genocidal war against Native Americans and the African slave trade. In his writings and in the organizations he joined, he worked for full rights for people of all colors. His calls for liberation and equality for women were similarly unequivocal and visionary. The foundation of Skidmore’s work was his linkage of human freedom to cooperative economics. He called for the producers, Black and white, slave, and wage-slave, male and female, to seize the means of production. This put him at odds not just with the ruling class, but with liberal abolitionists and others who did not share his view that tyranny was inextricably connected to the concentration of wealth in a few hands” (pp. 9-10). A card-carrying member of a party that was yet to be established!

Some of the most historically impactful stories in the book deal with strikes in various industries—garment, railroad, armaments, electrical workers, teachers, precious metals, and bridge builders, among others.

A four-page story relates the lives and careers of Bert and Katya Gilden of Bridgeport, longtime CPUSA members and organizers. In their spare time, they wrote fiction and are best known for Hurry Sundown. Another of their novels was Between the Hills and the Sea, among whose characters Mayor Rod Kearnsey is clearly modeled on Bridgeport’s longtime Socialist Mayor Jasper McLevy—who merits a few pages himself. Why did voters elect and reelect McLevy, who served from 1933 to 1957? What material difference did it make to Bridgeport to have a Socialist mayor?

Several chapters focus on national mobilizations and their Connecticut contingents, for example, the 1932 Bonus Army—World War I vets who’d been promised a bonus payout starting in 1945 (!)—by which point many of them would already have died—but who, during the depths of the Depression, badly needed that income now.

A unit on the Eastons, a talented African-American family in New England, who eventually settled in the Hartford area, dates them from the 1690s forward to the end of the 19th century. Other stories speak of the end of slavery in Connecticut in 1848, challenges to the state’s voting laws, and groups from the state that funded schools for freed former slaves in the Reconstructionist South. Malcolm X’s many visits to the state are documented, and the Black Panther Party and its trials are discussed in several places. We also learn about Edward Alexander Bouchet, an early Black student at Yale (perhaps the first), the first African-American to earn a Ph.D. in any field—physics in his case. Other notable Black personages with their own set pieces include playwright Louis Peterson, legal mastermind Constance Baker Motley, welfare warrior Isabel Blake, and trailblazing journalist Les Payne. One chapter features several items about Latinx in the state.

Radical Connecticut contains a wealth of elucidating commentary on a number of important women: Olympia Brown, America’s first ordained woman minister, muckraking journalist Ida Tarbell, Wobbly and later UAW organizer Matilda Rabinowitz (later Robbins), the radical thinker Helen Keller, who lived in Connecticut from 1939 until she died in 1968, and suffragist Josephine Bennett.

Several items appear on Connecticut students, organizing against war and for civil rights. The life of one Ulysses DeRosa, an Italian immigrant and tireless agitator, is movingly recounted in a longish (nine pp.) biography. Peace activist and child and baby care doctor Benjamin Spock gets a story, too, as does Prof. Staughton Lynd, a Yale history professor who accompanied Herbert Aptheker and Jarvis Tyner on a fateful mission to wartime North Vietnam in December 1965. The concluding paragraph on him, written in the present tense, says he is “Eight-five [sic] years young at the time of this writing” (p. 198). He died Nov. 17, 2022—early enough, presumably, to warrant an update before publication.

Several pieces are devoted to the Vietnam War years. The Moratorium (Oct. 15, 1969) was observed in a number of cities and towns across the state. My eye caught this tidbit (p. 203): “New Britain’s Mayor Paul Manafort, meanwhile, ordered 250 American flags to be flown in the city to protest the peace actions” (p. 203). I was curious red-white-and-blue, so I looked up this guy: Sure enough, he was the father of the later Donald Trump operative Paul Manafort, convicted and ordered to jail over charges of Russian involvement in Trump’s presidential campaign, whom The Don pardoned on Dec. 23, 2020.

Speaking of presidents, the authors include a chapter on the infamous “Business Plot” against FDR that implicated a Wall Street exec living in Greenwich who later became a U.S. Senator from the state—none other than Prescott Bush, whose son George H.W. and later grandson George W. both became U.S. presidents.

Two short items appear in the LGBTQ chapter, one of them about the Kalos Society, which I was involved with for a time in the mid-1970s. I was sorry that an affair I was intimately connected to didn’t make it into the book. Some well-meaning West Hartford citizens (where I resided) wanted to erect a Mandala in the center of town memorizing the Jewish victims of the Holocaust. I spearheaded a small group asking to be heard, before this project got much farther along, about including other communities as victims of the Nazis—homosexuals, Roma people, disabled persons, etc. We met with brick-wall resistance, and the issue spilled out into the press, with hearings before the local Human Rights Commission. The upshot of it was the organization of the first public program in the U.S. commemorating the plight of homosexuals under the Nazis, the men of the Pink Triangle (lesbians were largely untouched by Nazi policy). Since then, recognition of other victims of Nazi persecution regularly receives inclusion in public forums. In the end, the Mandala was never built; I suspect that town leaders might have feared it would always be a contentious site vulnerable to ongoing protest and decided they didn’t need that.

And while I’m on the subject of moi, I’d like to mention a year and a half’s worth of production (1975-1977) of a weekly radio hour on WWUH, the University of Hartford station, that I hosted with help from a small team of associates, called “None of the Above.” The show featured news and music of the ongoing radical and queer movements and was the first in the state to broadcast music from Barbara Dane and Irwin Silber’s record company Paredon, and the new feminist albums from singers like Meg Christian and Holly Near. Homophobia got me kicked off the air.

Clifford Odets’ play Waiting for Lefty gets its own article that focuses on early productions in Connecticut cities in 1935. Later chapters discuss the Group Theatre, the Federal Theatre Project, Eugene O’Neill, Arthur Miller, Mark Twain, Walt Kelly, Art Young, Martha Graham, Anna Sokolow, and other creative types.

There’s material about the First Red Scare after WWI and the later HUAC anti-Communist hearings.

I believe I gave this book a careful reading, but unless I overlooked it somehow, it might have been of interest to readers to learn the significance of Connecticut as “The Constitution State,” since it’s included in the very title of the book. It is also known as “The Nutmeg State,” which also might have merited a little explanation.

A few typos and grammatical gaffes inevitably creep into almost any book one picks up today, and Radical Connecticut is no exception. The very name of the publisher is rendered in two different ways—both Hard Ball Press and Hardball Press. And on the copyright page, the mailing address of the press has a misspelled street name! A purported witch, Alse Young, hanged in 1647 in Hartford, the authors claim “was born around 1600 in Windsor, Connecticut” (p. 250), rather impossible since the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth, Mass., only in 1620. Twelve small photos are deployed across two pages.

Ten years ago I had the pleasure of reviewing Steve Thornton’s A Shoeleather History of the Wobblies: Stories of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) in Connecticut, and the current volume is conceived in much the same vein. In fact, the present volume reprints several stories from the Wobbly book. Thornton and his collaborator Andy Piascik have been tilling the fields of this history for years, and it is evident that many of the short episodes of radical history that they gather here have been previously published in even more ephemeral places. The Table of Contents lists the titles of all the individual articles and their authors. A bibliography of books and sources at the end gives the place and date of original publication.

More than once I was struck by the authors’ inattention to tenses so that what seemed timely and pertinent at the moment of first appearance, has now entered the historical record and could have been appropriately, and easily, reworded. For example, one story begins, “This Fall marks 50 years since the establishment of Housatonic Community College…” (p. 31). Another, with questionable connection to Connecticut other than the fact that Thornton interviewed the daughter of Pierce Wetter, a significant IWW member, reads, “Now, living in a Hartford-area retirement community, Bobbie begins to remember more…” (p. 37). The story “Grocery Store Workers Take on Billion Dollar Multinational,” about a 2019 strike against Stop and Stop (pp. 78-81) is entirely written in the present tense.

The absence of an index detracts from the book’s utility, especially within the 22 thematic chapters—such as “Movements of the Unemployed,” “People on the Job,” “Resisting Government Repression,” or “Peace, not War,” there is considerable overlap. And within those subheadings, one might find entries dating decades or even centuries apart. The volume has an episodic quality that eschews chronology: It almost doesn’t matter in what order you read the individual essays. Those who enjoy dipping into history without trying to uncover a longer connecting narrative arc will be content in these pastures.

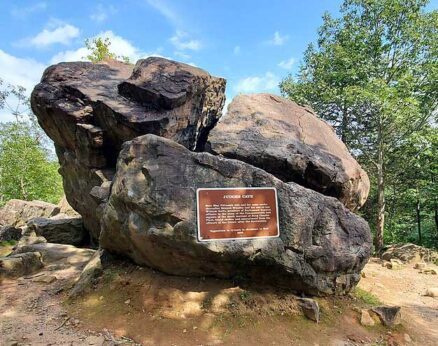

I noticed a few unfortunate lacunae in the book—though in their Introduction the authors pointedly admit the book “is in no way comprehensive.” There was no discussion of the Three Judges—Edward Whalley, William Goffe, and John Dixwell (who all lent their names to major streets in New Haven)—among the 59 British judges who sentenced King Charles I to his death in 1649. They later escaped to the American colonies and hid out there. “Judges Cave” in New Haven is a designated historical site where they decamped for a time, protected by the sympathetic community.

Young Nathan Hale, captured by the British and executed as he pronounced the noble words “I regret that I have only one life to give to my country,” is mentioned only in passing (p. 7) in connection with a story about Revolutionary figures Caleb Brewster and Benjamin Tallmadge, but given his renown, Hale could well have merited an essay on his own.

The famous case of the Amistad ship could have been included—wherein escaped enslaved Africans were granted their freedom in 1839.

This is a little obscure, but with me it’s personal: The Gertrude Hart Day Co-Operative Nursery School operated for a number of years in the New Haven-Hamden area from the late ’40s to the mid-’50s. I was reminded of it recently when I read Gerald Horne’s new book Armed Struggle? about the choice revolutionary activists had in the civil rights and Vietnam era whether or not to pursue racial justice and economic freedom through violent confrontation. In a background note on Panther John Huggins, Horne indicates that he was originally from New Haven, where his parents had been CPUSA members. I attended that nursery school and was a classmate of Huggins, and now I am wondering if that school was a project of mass outreach by the Party. I remember my mother describing it as a place where, with a common interest in their children’s education, Black, Jewish, white, and other parents would be able to come together and get to know each other around their mutual concerns.

Along these lines, I believe a major omission in this volume is at least an introductory overview of the CPUSA’s recent history in Connecticut, one of the most active and successful districts in the Party. Especially in New Haven over the last several decades, the CP has worked assiduously in the union organization movement and in citizen involvement in elections. Candidates in or aligned with the Party have been elected to public office with apparently little need to sanitize their connections to the community. The Party has positively changed the valence of politics in the state. This remarkable phenomenon certainly deserved a salute in Radical Connecticut.

The authors acknowledge the great forerunner in writing history from the ground up, Howard Zinn, and also name other writers who have tilled those same fields. At the same time, while also acknowledging their own limitations as something other than professional historians, “We do believe,” they write, “that people’s history can be told by others besides academics. Many people have spent much, if not all, of their adult lives participating in organizations, movements, campaigns, and other efforts such as those described in this book. This accumulated wealth of experience and knowledge is of the utmost value and should be considered a vital contribution to historian Eric Foner’s concept of a ‘usable past.’”

The authors acknowledge the great forerunner in writing history from the ground up, Howard Zinn, and also name other writers who have tilled those same fields. At the same time, while also acknowledging their own limitations as something other than professional historians, “We do believe,” they write, “that people’s history can be told by others besides academics. Many people have spent much, if not all, of their adult lives participating in organizations, movements, campaigns, and other efforts such as those described in this book. This accumulated wealth of experience and knowledge is of the utmost value and should be considered a vital contribution to historian Eric Foner’s concept of a ‘usable past.’”

Yes, this is a quirky book, but saturated with rich content. It reminds me of the Federal Writers Project during the New Deal when unemployed writers were hired to research and write books about each state’s history. May this book spawn at least 50 more in its wake!

Andy Piascik and Steve Thornton

Radical Connecticut: People’s History In The Constitution State

Brooklyn, N.Y. Hard Ball Press, 2024

Paperback, 356 pp., illustrated

ISBN: 979-8-9898025-0-0