ILCA, Honorable Mention, Best Feature Story

The system we live under is one embedded in sexism, racism, and white supremacy. It is one that allows a man like Donald Trump to reign as the so-called “leader of the free world,” even as accusations of sexual assault and treason swirl around him, even as he threatens working people and their livelihoods. Despite all this, however, the American people have not been completely demoralized. They are pushing back against racism, unjust laws, and abuse of power and have scored some victories while opening a road forward in the new year.

This progress has not just happened on its own, though. It is built on foundations laid by the work of countless other activists and people throughout our country’s history—those who have waged their own battles against the same foes of true democracy. One of the key elements in these fights has been the work of the independent press, which has shaped and broadcast the narrative of resistance.

This progress has not just happened on its own, though. It is built on foundations laid by the work of countless other activists and people throughout our country’s history—those who have waged their own battles against the same foes of true democracy. One of the key elements in these fights has been the work of the independent press, which has shaped and broadcast the narrative of resistance.

Today, it is the #MeToo and #TimesUp movements that are making a lasting structural and cultural impact to the world in which women have to live and work—a world too often characterized by harassment and sexual violence from powerful men. One of the most prominent champions of the movement, along with on-the-ground activists like Tarana Burke who began the #MeToo campaign, has been Oprah Winfrey. The media mogul is no stranger to adversity; she battled poverty, childhood sexual assault, and racism to become one of the most successful women of our time.

Oprah also, as exemplified by her recent Cecil B. DeMille Award acceptance speech at the Golden Globes, understands that these campaigns can only go so far without the help of the press, which Trump and others like him have constantly been trying to undermine, intimidate, and silence.

As she noted, “We all know the press is under siege these days, but we also know that it is the insatiable dedication to uncovering the absolute truth that keeps us from turning a blind eye to corruption and to injustice…to tyrants and victims and secrets and lies. I want to say that I value the press more than ever before as we try to navigate these complicated times, which brings me to this: What I know for sure is that speaking your truth is the most powerful tool we all have.”

Although Oprah acknowledges the recent high-profile activists and celebrities that have come out against sexual harassment, she also understands that there are countless others, such as domestic workers, farm workers—working-class women of all professions and walks of life—whose names we may never know but who have led, and continue to lead, the charge on this fight.

In that same speech, Oprah brought attention to one such woman whose story of resilience against sexual assault and racist intimidation helped lay the groundwork for the fight against such atrocities today. That woman was Recy Taylor.

“In 1944, Recy Taylor was a young wife and a mother. She was just walking home from a church service she’d attended in Abbeville, Alabama, when she was abducted by six armed white men, raped, and left blindfolded by the side of the road coming home from church. They threatened to kill her if she ever told anyone, but her story was reported to the NAACP, where a young worker by the name of Rosa Parks became the lead investigator on her case, and together they sought justice. But justice wasn’t an option in the era of Jim Crow. The men who tried to destroy her were never persecuted. Recy Taylor died 10 days ago, just shy of her 98th birthday. She lived as we all have lived, too many years in a culture broken by brutally powerful men. For too long, women have not been heard or believed if they dared to speak their truth to the power of those men. But their time is up. Their time is up,” Oprah said in her speech.

Despite warnings from her rapists, Recy Taylor reported the horrible incident to the authorities. This was a life-threatening move for a Black woman in the Jim Crow South of the 1940s. Not only did Taylor report it to the authorities, however, she also took her story to the press. One of the few news outlets that was willing to tell Taylor’s story, and put pressure on the fight for justice for her, was the Daily Worker—the predecessor to today’s People’s World.

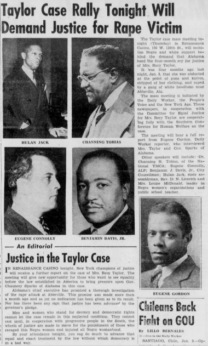

In November 1944, Daily Worker journalist Eugene Gordon reported on Taylor’s story and the fact that all of her rapists were exonerated. He also noted that Taylor’s case was given little to no coverage in the mainstream press. In fact, her story was actively buried, prevented from seeing the light of day by white-run newspapers. Gordon expressed that the Daily Worker, aside from the Black press, was the only one to report on Taylor’s case, knowing that the prejudice against her plight was both sexist and racist.

The Daily Worker would go on to do several articles, bringing the nation’s attention to Taylor’s case. Gordon, along with other activists, would found the Committee for Equal Justice to organize others to join in supporting her struggle. He, along with colleagues, wrote a pamphlet titled “Equal Justice Under the Law,” which featured a direct interview with Taylor, allowing her to speak her own truth to the public.

An editorial in the January 4, 1945, Daily Worker called on the people of New York to hit the streets and rally to demand justice for Recy Taylor and all women who were brutalized and ignored.

“Men and women who stand for decency and democratic rights cannot let the case remain in this neglected condition,” the editorial declared. “They cannot rest until, in cooperation with progressive people in the South, the wheels of justice are made to move for the punishment of those who ravaged this Negro woman and injured all Negro womanhood.”

All of this happened in the 1940s—almost 75 years ago.

But this pioneering journalism by the Daily Worker was not some isolated incident related to just one case. It is part of those foundations mentioned at the beginning of this article—the foundations upon which today’s continued fights for justice are built. It is an example of the essential role that the press—and especially grassroots outlets like People’s World—continue to play in these battles. The protection and the support of the press are crucial now, more than ever, as there are people in power who are on an active mission to extinguish any beacons of resistance and truth.

Taylor’s story, and countless others, should not be lost and forgotten as footnotes in history, or outdated occurrences. The battle by Taylor, and the role of the Daily Worker, helped lead us to this moment of truth-seeking in which we stand today.

“I just hope that Recy Taylor died knowing that her truth, like the truth of so many other women who were tormented in those years, and even now tormented, goes marching on. It was somewhere in Rosa Parks’ heart almost eleven years later, when she made the decision to stay seated on that bus in Montgomery, and it’s here with every woman who chooses to say, ‘Me too.’ And every man—every man who chooses to listen,” Oprah noted.

Her words harken back to what Eugene Gordon said in 1944 when he helped bring Recy Taylor’s story to the world: “Mrs. Taylor was not the first Negro woman to be outraged [sexually assaulted], but it is our intention to make her the last. White-supremacy imitators of Hitler’s storm troopers will shrink under the glare of the nation’s spotlight. The attack on Mrs. Taylor was an attack on all women… No woman is safe or free until all women are free.”

The Daily Worker, and others, called for something of a #TimesUp movement against injustice decades ago. We continue to march in that tradition, telling that truth today.

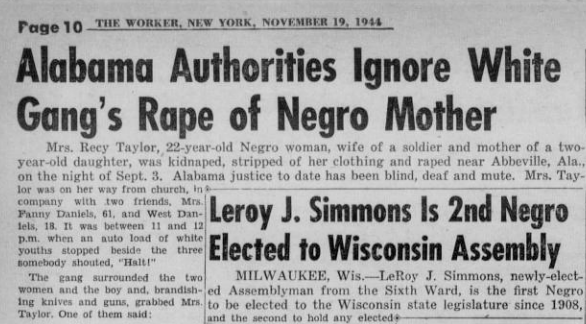

Below you can find Eugene Gordon’s first article on Recy Taylor’s case. A review of the new documentary film, “The Rape of Recy Taylor” can be found here.

“Alabama authorities ignore white gang’s rape of Negro mother”

By Eugene Gordon

From the November 19, 1944 edition of the Daily Worker.

Mrs. Recy Taylor, 22-year-old Negro woman, wife of a soldier and mother of a two-year-old daughter, was kidnapped, stripped of her clothing, and raped near Abbeville, Ala., on the night of Sept. 3. Alabama justice to date has been blind, deaf, and mute.

Mrs. Taylor was on her way from church in company with two friends, Mrs. Fanny Daniels, 61, and West Daniels, 18. It was between 11 and 12 p.m. when an auto load of white youths stopped beside the three. Somebody shouted, “Halt!”

The gang surrounded the two women and the boy and, brandishing knives and guns, grabbed Mrs. Taylor. One of them said:

“This girl is wanted by Sheriff Gamble for cutting a white boy in Clopton this evening. Sheriff Gamble doesn’t know her, but we do, by the clothes she’s wearing, and he has us out looking for her. You are the one, and we must take you, dead or alive.”

She was shoved into the car and driven in the direction of Abbeville. It turned off the road, however, at Three Points, heading toward the old Columbia Highway.

HUNT ATTACKERS

Mrs. Daniels and West went to the home of a white man named Cook. Hearing their story, he asked her to stay with his sick wife. He and a man named Bennie Corbitt and Mrs. Taylor’s father sought High Sheriff George Gamble and not finding him, got Deputy Sheriff Louis Corbitt. They hunted for the hoodlums.

Mrs. Taylor, the next day, staggered home, naked, dazed, and bleeding. She said the gang had driven her out of the Old Columbia highway, while she pleaded with them for her baby’s and her husband’s sake, not to kill her. Stripping her, they forced her, at the point of a gun, to submit to one after the other of the six or seven members of the gang.

Early in the morning, she was blindfolded and driven back to Abbeville. They dumped her out at Charlie Norton’s Corner, ordering her not to remove the blindfold until they were gone. Deputy Sheriff Corbitt was with her father when she staggered in.

Corbitt, with her detailed description of the car, found it and its driver, Hugo Wilson. He arrested Wilson, who named Penute Hasting (or Hasty), Skipper Reeves, Dillard York, Luther Lee, and two or three others, as accomplices. Mrs. Taylor confirmed these identifications.

ALL EXONERATED

Deputy Sheriff Corbitt, High Sheriff Gamble, a solicitor, and Mrs. Taylor drove to the scene of the crime. They admitted that all evidence tended to prove her charges. Yet, when the Grand Jury met on Oct. 9 and listened to her, Mrs. Daniels’, and West Daniels’ story, every member of the gang was exonerated.

What have Alabama authorities done since then as protector of its citizens’ rights? Alabama, typical of the South in general, boasts of its concern for its womanhood.

The answer is found in reply to a telegram sent by John McCune, editor of the Birmingham Age-Herald to the Daily Worker. He wired that his paper had never heard of the case.

It is clear that if the state had taken action, it would have been known to the press of the whole South. Every Southern newspaper played up the “rape” of the unnamed wife of a white soldier in Florida. They had a grand time also when the alleged rapists, the youngest of whom was 16, were burned to death in Florida’s electric chair.

Alabama has done nothing about Mrs. Taylor.

The Daily Worker is the only newspaper, aside from the Negro press, which has mentioned this case.

The whole country must be aroused to action against this and other similar outrages against the Negro womanhood.