December 24 marks the death in 1964 of Claudia Jones. A member of the U.S. Communist Party’s National Committee and executive secretary for its Women’s Commission, Jones died in England, nine years after her deportation from the U.S.. On

the 52nd anniversary of her death, it is a timely occasion to recall her life and contributions. Her analysis of black women’s oppression and her vision of black women as political activists remain meaningful today.

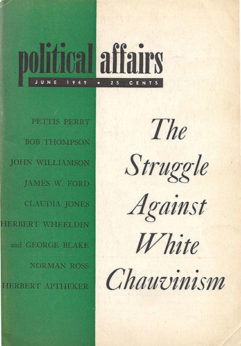

Her 16-page article titled “An End to the Neglect of the Problems of Negro Women,” appeared in the June 1949 issue of  Political Affairs (available in Spanish here). There, Jones describes the origins and varieties of oppression against black women. Her message is as relevant today as ever. The ripple effect of what happens to women adds to the staying power of Jones’ ideas: children’s education, health, and even survival depend on women flourishing. Men who no longer dominate women can themselves also gain a measure of liberation.

Political Affairs (available in Spanish here). There, Jones describes the origins and varieties of oppression against black women. Her message is as relevant today as ever. The ripple effect of what happens to women adds to the staying power of Jones’ ideas: children’s education, health, and even survival depend on women flourishing. Men who no longer dominate women can themselves also gain a measure of liberation.

Jones begins: “Negro women – as workers, as Negros, and as women – are the most oppressed stratum of the whole society.” There is “growth in the militant participation of Negro women in all aspects of the struggle for peace, civil rights, and economic security.” In fact, “the capitalists know, far better than most progressives seem to know, that once Negro women take action, the militancy of the whole Negro people, and thus of the anti-imperialist coalition, is greatly enhanced.”

Jones identifies black women’s special capabilities. “From the days of the slave traders down to the present,” they’ve been the guardians, protectors, and advocates for their children and families. Thus, “it is not accidental that the American bourgeoisie has intensified its oppression, not only of the Negro people in general, but of Negro women in particular.” She observes black women organizing their own mass organizations; they “are the real active forces – the organizers and workers – in all the institutions of the Negro people.”

Claudia Jones sees “a developing consciousness on the woman question today.” Therefore, “the Negro woman who combines in her status the worker, the Negro, and the woman, is the vital link to this heightened political consciousness.”

Jones points to economic abuse of black people. She examines the plight of domestic workers and organized labor’s exclusion of black workers. But she finds the line separating race–based oppression from oppression as workers to be blurred. That’s natural, because black women “far out of proportion to other women workers, are the main breadwinners in their families.” She calls upon unions to take in black women and for domestic workers to be organized.

Employed white women, she notes, were receiving twice the hourly wage granted to black women workers. The median family income of whites in northern cities exceeded that of black families by 60 percent. (In 2015, the average hourly income for white and black women workers was $17 and $13, respectively; white families’ median income that year was 70 percent higher than black families’ income.)

Jones laments that, “The maternity death rate for Negro women is triple that of white women.” She points to high death rates for black children. (Death rates for black mothers as recently as 2012 were almost four times that of white mothers. Yes, death rates for black infants and older children in Jones’ era were twice those for white children, and that hasn’t changed.)

Jones castigates white racism and sexist attitudes. She objects to the label “girl” applied to older black women, to progressives’ and even Communists’ hesitation at socializing with black women associates, and to Communists’ reluctance to recruit black women, alleging they are “too backward.” She denounces “bourgeoisie ideologists” for relegating all women to “kitchen, church, and home,” but also for ignoring the presence of black domestic workers “in other people’s homes.” She thinks black men have “a special responsibility in rooting out attitudes of male superiority as regards women in general.”

Included in Jones’ survey are emblematic news stories of assaults on black women and snippets of dialogue highlighting regressive attitudes. She identifies individual black women who resisted and/or organized labor actions. Jones argues for black women – the “most exploited” women – joining progressive organizations and the Communist Party.

Through “active participation” as workers in the “national liberation movement,” black women will “contribute to the entire American working class, whose historic mission is the achievement of a Socialist America – the final and full guarantee of women’s emancipation.”

Her essay concludes: “The strong capacities, militancy, and organizational talents of Negro women can…be a powerful lever for bringing forth Negro workers – men and women – as the leading forces of the Negro people’s liberation movement, for cementing Negro and white unity in the struggle against Wall Street imperialism.”

Claudia Jones wrote and acted by the light of her own life experience. Extreme poverty forced her family’s emigration from Trinidad to New York. Her over-worked mother died there, and living conditions for Claudia and her sisters deteriorated. Jones spent a year recuperating in a tuberculosis sanatorium. She was a superior high school student, but instead of college, she worked in laundries and factories to support her family.

Soon – in 1936 – she was organizing for the Young Communist League and working for the Communist Party’s Daily Worker newspaper. She moved to writing and editorial assignments with other Party publications and to the Party’s “Negro Commission.” Her “Half the World” column – meaning women – appeared regularly in the Daily Worker.

Claudia Jones’ life took a tragic turn. Tried and imprisoned under the anti-communist Smith Act, she was deported to England in 1955. She died prematurely at age 49. Elements of Caribbean culture and politics, and of black people’s nationalism, had informed Claudia Jones’ activism and writings in the United States. In London, she founded and edited the West Indian Gazette. To counter “white racists,” she organized the Notting Hill Caribbean Carnival, which continues to this day.