Listening to the 28th National Convention of the Communist Party, USA, on the Internet inspired me to relive the rich and vibrant history of our party. Men and women such as Paul Robeson, Claudia Jones, W.E.B. DuBois, Benjamin Davis and Lucy Parsons have all had a great influence on me, as shining examples of political activism and revolutionary struggle. A comrade who has been a particular inspiration to me is Hosea Hudson. Although his legacy remains largely uncelebrated, his work as a Black union leader and Communist organizer was extremely important.

Hudson was born into a poor sharecropping family in Wilkes County, Ga., in 1898. Life in the Deep South was extremely difficult. Early encounters with lynch mobs and oppressive landlords left Hudson traumatized. However, his experiences gave him a keen awareness of social and economic conditions that he would draw upon later in life.

Hudson was born into a poor sharecropping family in Wilkes County, Ga., in 1898. Life in the Deep South was extremely difficult. Early encounters with lynch mobs and oppressive landlords left Hudson traumatized. However, his experiences gave him a keen awareness of social and economic conditions that he would draw upon later in life.

Hudson married Lucy Goosby at the age of 19, and they had a son in 1920. In 1922, a family crisis and a boll-weevil infestation that destroyed their crops prompted Hudson to seek employment in Atlanta, where he heard that he could make a staggering five dollars a day. He moved to the city temporarily to become a railroad laborer, but soon resented the long hours and exhausting conditions working the coal chutes.

He rejoined his family and relocated to Birmingham, Ala., where he became both a skilled iron molder and a successful quartet singer. As a member of the L&N quartet (named after the local L&N Railroad), he was known as one of the best bass singers around. His group was given a weekly spot on local radio, the first Black quartet broadcast in the city.

Hudson remained relatively uninvolved in politics throughout the 1920s, but as the Great Depression aggravated the already difficult living conditions of poor Blacks, his resentment for the injustices suffered by his people intensified. In 1931, Al Murphy, a young Black worker and member of the Communist Party, USA, invited Hudson and a handful of other workers from Hudson’s foundry to a meeting to discuss politics. At the end of the meeting, Hudson and his companions joined the party, and Hudson was elected unit organizer for his plant.

Within a year, Hudson was fired from his job and forced to accept odd jobs under assumed names. As the Depression worsened, Hudson worked with the party to set up unemployed committees to help secure welfare payments and protect laid-off workers against evictions.

In 1934, Hudson traveled to New York to attend a 10-week CPUSA national training school, where he studied Marxist theory and learned to read and write. Returning to Birmingham, in 1937 he founded the Right to Vote Club, which sought to educate Blacks and other poor people about voter disenfranchisement and the procedural and legal requirements of voting. The club quadrupled the number of Black voters in Jefferson County between 1938 and 1940.

Hudson also worked for the Work Progress Administration and joined the Workers Alliance, the national organization that represented WPA workers in Birmingham. He helped transform the conservative, predominantly white group into an integrated, Communist-led labor union. Hudson served for two years as vice president of the Birmingham and Jefferson county branches of the Workers Alliance.

When World War II broke out and the economy shifted to the war effort, Hudson resumed iron molding and became involved in the United Steelworkers of America. He successfully spearheaded an effort to unionize his plant, and was elected president of newly created USW Local 2815. Under his leadership, working conditions in his foundry were improved and wages more than tripled. During this time, Hudson was also a delegate to the Birmingham Industrial Union Council and vice president of the Alabama People’s Educational Association, the renamed state section of the CPUSA after it was reorganized nationally as the Communist Political Association.

Hudson’s rigorous political life and the anti-Communist hysteria of the postwar era took a toll on him. His 30-year marriage ended in 1946, and in 1947 he was fired from his job and blacklisted for being a Communist, stripped of his positions in the USW, and expelled from the Birmingham Industrial Union Council. Forced to conceal his identity until 1956, he lived in Atlanta and New York City, and eventually moved to Atlantic City where he worked as a janitor, continuing his CPUSA membership and community activism.

In 1985 Hudson moved to Gainesville, Fla., where he died three years later.

Returning briefly to the South in 1964, Hudson was impressed with the dramatic social changes that had occurred, including the slow abandonment of Jim Crow laws, the rise in economic well-being for some Blacks, and the emergence of an influential Black political leadership. Despite these achievements, Hudson noted in his memoirs, “The sufferings and oppression of the vast mass of Black, Chicano and Puerto Rican people remain at an increasingly unbearable level. Unemployment, lack of housing, ghetto misery, arrests, frame-ups, the murder of innocent men and women — all these increase, and only basic changes in the structure of society will solve these terrible conditions.”

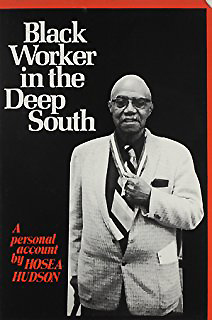

While always striving towards the greater goal of changing the system, Hudson centered his effort on alleviating the day-to-day misery of the oppressed. He remained an active organizer and outspoken proponent of communism until the end of his life. Two autobiographies have helped him gain the recognition he deserves. The city of Birmingham proclaimed February 26, 1980, as Hosea Hudson Day, and gave him the key to the city in honor of his outstanding civil rights work. Today, as we mark the 40th anniversary of the Voting Rights Act, is a good time to draw inspiration from the life of Hosea Hudson.

Bryn Lloyd-Bollard (ballo@conncoll.edu) is a student activist.

The Hosea Hudson papers are archived at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, located in New York City.

In the photo on the book cover, Hosea Hudson wears a lanyard with the key to the city of Birmingham. It was presented to him in 1980 by then-Mayor Richard Arrington, the first African-American mayor of the city of Birmingham, Alabama.