This is a chapter from Tim Wheeler’s forthcoming memoirs. Eds.

PORT ANGELES, Wa. —- One day in 1953 Fred Gaboury invited me to come to work with him so I could witness first hand his skill in rigging a spar tree high in the foothills of the Olympic Mountains.

I eagerly accepted. I was only 13 at the time but Fred may have seen in me a future choker-setter, faller, or even a topper like him. Fred had rugged good looks. He had broad shoulders and snapping blue eyes and wavy golden hair. Movie star handsome, he should have been a heartthrob. Yet his speech was a steady stream of unprintable four-letter words. Somehow, Fred didn’t remind me of Gary Cooper after I had heard him utter a stream of profanity.

I had joined in the struggle to defend Karly Larsen, vice president of the Western Washington division of the International Woodworkers of America. A bunch of left-wingers, including my parents and me, met one morning at Fred and Betty Gaboury’s house in Port Angeles where we divided up piles of leaflets calling for justice for Larsen and repeal of the union-busting Taft Hartley Act. That Cold War statute outlawed members of the Communist Party, like Karly Larsen, from serving as leaders of unions even if duly elected by the membership.

I was teamed up with Fred’s younger brother, David, in the door-to-door distribution of that leaflet. Fred was elated by the success of the distribution in a mill town, center of logging and other forest-product industries.

The night before the long trip out to the West End of Clallam County, I spent the night at Fred and Betty Gaboury’s house. Fred woke me up at 4:30 a.m. and fed me a breakfast of flapjacks soaked in butter and syrup. In his hast, he burned the pancakes badly. Fred was always in a hurry.

In the pitch dark, we boarded the Weyerhaeuser crew bus in Port Angeles along with 15 or 20 other loggers. They came on to the bus quietly, still groggy in the morning chill. They were dressed in their tin hats, flannel shirts and jeans chopped off just below the knees. The jeans were held up by wide, brightly colored galluses. They wore high caulk boots bristling with spikes from the soles and heels to give them extra footing in the slippery underbrush on the deadly mountainsides.

The crew bus roared at breakneck speed out twisting Highway 101 around Lake Crescent. About twenty miles west of the lake, we made a left turn onto a gravel road that soon turned into a dirt track that wound its way up the mountainside, higher and higher. The crew bus pitched wildly as it toiled its way up the muddy track. The crew snored peacefully.

Soon we pulled into a staging area that had been cleared in the deep forest. We were so high on the mountain we could look out to the east. Dawn was breaking over the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Mount Baker gleamed like a pink strawberry sundae in the morning sun. The San Juan Islands lay darkly in the glittering waters of the Salish Sea.

Sitting in the staging area was an old “donkey” engine with a heavy steel cable for pulling the logs off the mountainside.

Standing alone beside the donkey was a Douglas fir nearly 200 feet high. It would serve as the spar tree once Fred had climbed and rigged it. He strapped the spikes onto the inside ankles of his boots, whipped the steel-core lifeline around the tree and secured it to the belt around his middle. He also secured a rope to his belt.

Then he pushed his tin hat back from his brow and began to walk his way up the tree, stopping every few steps to whip the lifeline higher on the tree trunk. When he reached the first branch, he pulled up a chain saw. Hanging in midair, he pulled on the starter cord until the saw sputtered into life. He cut off the branch above him, swinging around out of the way as the thick branch broke away and plunged to the ground.

Higher and higher he climbed, cutting off the limbs as he worked his way up to the treetop. When he was one hundred seventy feet up, he cut off the top of the tree. He worked the chain saw around the trunk so it would break cleanly and not split the top of the tree. That was a mishap that could ruin the spar tree and also kill the rigger.

Fred dropped his rope again and the crew below tied on a pulley. He pulled the pulley up and attached it to the top of the spar tree. He threaded the rigger’s line through the block and dropped the line back to the ground where the crew loaded the giant mainline block, an enormous pulley, and hoisted it back up to Fred. He attached that pulley and threaded the mainline through it. He also attached the four guy lines to keep the spar tree from swaying.

While he toiled high in the air, the ground crew was also hard at work. The tree fallers were out on the slopes with chain saws cutting down the trees. The catskinner, a cigarette dangling casually from his lips, was roaring back and forth with his D-9 crawler tractor smoothing out the staging area that the loggers called a “yard.”

By now, Fred had completed his task and descended with breathtaking speed to the yard. The donkey belched and roared, the mainline cable snaking the logs off the steep slopes and dragging them into the yard. A loader was picking up the logs one by one and loading them on the back of the first of several log trucks idling in the yard.

Years later, I watched Fred Gaboury win first prize in the high climbing contest during the logging show at the Sequim Irrigation Festival. He left the other contestants in the dust, racing up the 100-foot tree, his spurs flashing, the steel-core lifeline slapping as he raced up the spar tree and then slid back down.

Fred joined the staff of the People’s World in New York City when I was editor in the 1990s. He often wrote under the name “Hy Climber” as his byline and he served as our most able labor editor. I will always remember him with his Paul Bunyan hands pounding away on his desktop computer with fingers so thick he struggled to hit the right keys.

All of us loved Fred for his hard driving, if too profane, approach to the class struggle. He was out of the office interviewing workers on their picket lines. He got to know top leaders like previous AFL-CIO President John Sweeney and AFSCME leaders Gerald McEntee and Bill Lucy. He was on a first name basis with all these leaders. They respected Fred, knowing he had “paid his dues.”

Fred’s display of courage and skill that day gave me a special appreciation of workers in basic industry. They need a fighting union—and a political party—of their own to defend their interests toiling in the nation’s most dangerous industries.

When Fred Gaboury died in 2004, we ran this heartfelt obituary, and this from his memorial: What it means to be a Communist. Eds.

Fred Gaboury was a member of the Editorial Board of the People’s Weekly World/Nuestro Mundo and wrote frequently on economic, labor and political issues. Here is a small selection of Fred’s significant writings:

Eight days in May Birmingham and the struggle for civil rights

Remembering the Rev. James Orange

June 19, 1953: The murder of the Rosenbergs

World Bank and International Monetary Fund strangle economies of Third World countries

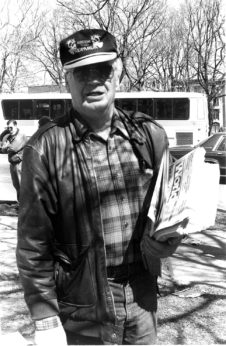

Photo: Fred Gaboury on a picket line interviewing workers. PW