Mozambique’s first nationwide Festival of People’s Dance happened 40 years ago this month. Starting in January 1978, millions took part throughout the country, building to a finale in the capital, Maputo, on the eve of Independence Day, June 25.

Three years after liberation from Portuguese colonialism, it was time to celebrate cultural freedom. The socialist government of the Mozambique Liberation Front (FRELIMO) was building the “Sociedade Nova” (New Society), and I was lucky enough to be there.

My wife and I were “co-operantes internacionalistas” (international solidarity workers) in the northern province of Nampula. Julia was its single dentist, I a schoolteacher.

I got involved with the festival because, as well as setting so-called “traditional” dances free from colonialist contempt and banning, it set out to reclaim their histories and document their music.

Since the Sociedade Nova did not yet have professional historians or ethnomusicologists, the task fell to amateurs like us, in schools and workplaces. For the next two years, I helped students and young teachers, often school-leavers themselves, in the “National Campaign to Preserve and Revalorize People’s History and Culture.”

Under the slogan “Our Old People are Our Libraries,” we went to the countryside to interview elders and research dances, instruments, and songs, leading to a follow-up festival in 1980. I lent my cassette recorder.

To mark the anniversary, I have digitized the cassettes, dubbed them onto CDs, and returned them to their originators. The idea took shape one afternoon on a London bus, when I sat opposite a father and his daughter.

From her tutu and his words, I knew they were going to a party. The traffic was making her restless. Dad got on his phone and talked loudly, as if to prove every language in the world is spoken on London’s public transport.

“E pa, que chatice, ’tou no maximbombo…” (Hey, what a drag, I’m on the bus).

The Mozambican word “maximbombo” caught my ear. We started talking.

“When did you live there?” he asked me.

“The late 1970s.”

“Hmm, os anos esquecidos.” (The forgotten years).

“Yeah, the socialist era.”

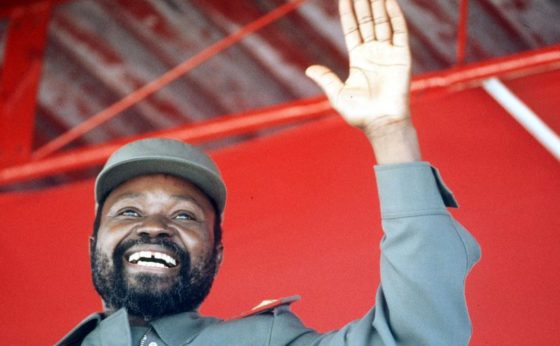

“E pa,” he smiled, “os sonhos de Samora!”

Samora’s dreams: Samora Machel, guerilla leader, first president of independent Mozambique, and incorruptible craftsman of the Sociedade Nova. “Papa Samora” was killed in 1986 when his plane flew into a South African mountain, with foul play by the Boers suspected.

I gazed at the streets, words from a Dylan song in my head: “You can be in my dream if I can be in your dream.” Machel was not the only one. In the ’70s, my friends in Nampula had let me into theirs. It was time to go back.

On the way, I found many ex-students and colleagues in Maputo. Their welcome was cautious, because they knew I would have to find a communal village in Erati District, where we did a lot of work: the Aldeia Comunal Samora Machel, at a place previously called Mejucu.

Be careful, they said. Communal villages were a thing of the past, except for occasional articles in the papers about co-operative versus individual farming.

They also told me about the village’s likely fate in the 16-year civil war (1977-92), the main event in Mozambican history since my time there. The fighting took place between FRELIMO and RENAMO, a dissident movement largely backed by white supremacist Rhodesia and apartheid South Africa.

With the coming of multiparty democracy in a UN-brokered peace settlement in 1992, Afonso Dhlakama’s RENAMO became the main opposition party. By then, FRELIMO had swapped socialism for the neoliberal embrace of Western donors. With the 1989 collapse of the Soviet bloc, there was no alternative.

“The village was a target in the war. It may not even exist today,” said an ex-student. “The inhabitants were probably killed or displaced—and, if they survived, life is short up there.”

A few days later, I was speeding into Erati with Dr. Artur Muloliwa, born in Nampula and medically qualified in Cuba. Muloliwa’s take on the Samora Machel village’s continuing existence was: “There’s only one way to find out.”

At the wheel of his “Champagne Corolla” (we named it after a song on my iPod), he reminisced about his years on Fidel Castro’s “Isla de la Juventud.” The setting sun flashed between the rocky outcrops of the Nampula countryside. Some were eye-catchingly anthropomorphic, rising hundreds of meters from the savannah.

“The village might be that way,” said Muloliwa, stopping at a turning by a string of food stalls. A “picada” (dirt track) led away.

In Makua, the local language, he asked youths on Yamaha 125s, purchased with wages from a U.S. mining operation, if they’d heard of the village. They gestured with their thumbs.

“Up there, two hours.”

We decided not to risk the picada. The surface looked both rutted and sandy and would probably get more so further from the tarmac road.

Next day, thanks to Erati’s director of health, we were offered a lift in a 4×4. The driver, “Motorista” Antonio, was delivering medicines to the village’s maternity unit.

The village was still called Samora Machel, apparently, but the inhabitants had dropped the title “communal.” Also, they no longer talked about “trabalho colectivo” (collective work). Nevertheless, they were known for good harvests resulting from “trabalho em conjunto” (teamwork).

“You don’t go hungry, there”, said Antonio.

We called at the village shop.

“I know you,” said a customer.

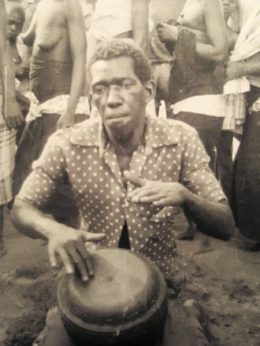

Fernando, drummer from 1978, hugged me. I produced my pack of CDs. Fernando led us to the house of Cipriano, another veteran. Cipriano had gone blind since ’78, when he used to drill the village militia, but it was clear that he remained highly respected. “He sees more than people with eyes,” said Fernando.

Residents of all ages came for CDs. Two women who demonstrated the dance “Etahurra” in 1978 ululated and did an impromptu performance with younger ones.

“I was volunteer No. 94 of the village’s first hundred members,” said Cipriano. “Twenty-seven of us are left. These are our children and grandchildren.”

His people’s dances, he assured us, were still performed.

“They carry our history. We are the subjects of Mpewe [Chief] Komala. He lives in a two-story house you passed on the ‘picada.’

“When the ‘ehopa’ [white toads] came, they offered his ancestor matches and soap. Komala said: ‘Don’t you know I am the Lord of Fire—and we make our own soap.’ They shot him.”

I remembered identical words from 1978. Cipriano, a youth at his elders’ feet back then, had become their guardian. His account of the 16-year war? “Oh, that period of destabilization. Yes, we were attacked. We had to sleep in the bush, but we returned.”

The phrase “message in a bottle” came to mind. Now that FRELIMO’s “socialist period” is over and Mozambique depends on the IMF and World Bank, I reflected on how it is discredited, just as people elsewhere focus on communist failures.

Yet I couldn’t help thinking again about “Samora’s dreams,” when political altruism—to serve the people—was the name of the game.

Samora’s dreams might be in ashes, but a few embers are alive. The story of the Aldeia Samora Machel is worth sharing, in case the man on the maximbombo’s daughter, and others like her, grow up to wonder, like Gramsci, whether the way things are is the way they have to be.

Richard Gray is a PhD student at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London. He worked in Nampula, Mozambique, for the Ministry of Education and Culture from 1977 to 1981. Graca Machel, president Samora Machel’s wife and later married to Nelson Mandela, was minister at the time. Since his recent visit to Mozambique, Richard has set up the Mejucu Charitable Trust, which supports Acamo Erati, a district branch of Mozambique’s national NGO for visually impaired people. To receive further info or make a donation, please contact him at richgray2007@hotmail.co.uk. This article originally appeared in Morning Star.