WhatsApp handles over one million voice calls a day, has over one billion users, and when it was bought by Facebook in 2014, Mark Zuckerberg’s company paid in excess of $19 billion for it. WhatsApp directly employs just 55 people.

So-called “digital work” is growing at an enormous rate all over the world, from platforms like Amazon’s “Mechanical Turk,” where individual workers register online to carry out any number of “human intelligence tasks” – writing short articles, filling in survey forms, choosing shop-front designs, or any number of small tasks, earning as little as $0.01 for completion. There are over 500,000 workers registered on this site, and there are others emerging like it.

Jobs and the AI revolution

The economic research firm McKinsey Global Institute has estimated that between 45 and 75 million jobs in the global economy could be lost to artificial intelligence (AI) machines and robots by 2025. Divided into “requesters” (organizations that want work completed) and “taskers” (workers who will do the work online), this new work market is truly and completely global. Workers in India will sit at home competing for jobs against workers at home in Europe, China, the U.S., Africa, or southeast Asia.

There is a growing temptation even among governments to replace public sector workers with machines. A 2016 survey by Oxford University and Deloitte shows that the British government, for instance, could cut 1.3 million jobs and replace them with information technology (IT), AI, digital procurement, or robots, cutting spending by billions of pounds by 2030.

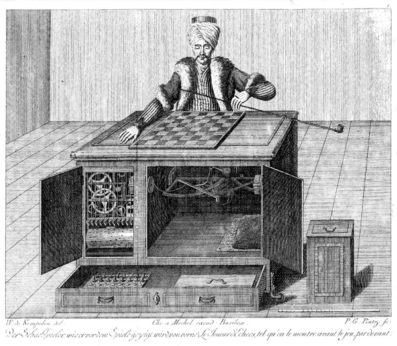

Artificial intelligence is the coming game-changer. Machines can play chess champions and beat them, diagnose patients more accurately and more quickly than humans, provide legal advice, and analyze data much more speedily. And they can do it all without holidays, sick leave, health insurance, taxes, or wages.

At the moment, they can only do what we teach them, they cannot “learn” without human assistance. But the DeepMind project – recently bought out by Google – believes it is about to solve that problem too. Reaching the so-called “singularity” – where machines can think and learn without humans – is likely to be on the horizon.

Global inequality may be out of control (eight individuals have the same wealth as the poor half of the globe’s population according to Oxfam’s latest report on global poverty), but there are millions of people who live in areas of the world with high unemployment and high rates of poverty – but have access to a computer and IT skills.

For many of them, these developments represent an opportunity to earn income that only previously seemed possible through migration.

Digital capitalism

In the face of this rapid and accelerating change, what happens to workers under global capitalism?

They face intense competition for their work. These “human intelligence” tasks most often require little in the way of professional or trained skills.

Each job is broken down into “doable” tasks and this de-skilling process separates out those tasks that are routine and can be done in less than 20 minutes by most people and those that may require further skills.

There is a justifiable fear that digital workers face a cliff-drop descent into casualized and self-employed work with few rights. For now, most workers who register as “taskers” appear to be doing it part-time to supplement wages, but this trend is on the decline.

In the next three years, there will likely be tens of millions of “taskers” on hundreds of platform sites, doing work for companies on the other side of the world. Some point to the benefits of “flexibility” that come with such a digital workplace. They say, for instance, these flexible work arrangements may benefit women’s advancement.

But this is part of what might be called the “myth of Uber.” The current pay scales on offer by these task platforms do not add up to a living wage anywhere in the world.

Tech for human benefit

This superb human technology could of course be harnessed to reduce working hours, eliminate repetitive work, and boost production to solve all the world’s problems. This has to be our serious aim, our cardinal bargaining point and our global ideal.

But in the meantime, we can identify many things that we can start doing now.

We can look at new ideas such as a robot tax (a tax relating to IT and AI use where workers are replaced), the notion of a universal income for citizens (funded partly by a robot tax), the setting up of agreements that control piece-rates and the linking of that with “fair work” style arrangements to specifically ensure that workers in poorer parts of the world will benefit from the surge in work and profits that will emerge from this so-called “fourth industrial revolution.”

We are going to need new kinds of union organization, built not so much around buildings and a bureaucracy, but around a new digital activist with a vast knowledge of these “human intelligence” tasks and their platforms and who can find a digital form of regular and reliable communication with workers around the globe.

There will be a need for activists who are multilingual, because Spanish, Mandarin, and French are more likely than English to be the first languages of these workers.

We have to look at digital actions that can easily disrupt global online operations. At the end of February, there was an outage at one of Amazon’s data centers for a few hours and hundreds of thousands of websites were affected.

Therein lies our potential.

Work will not entirely lose its geography, companies will still be based in “host” countries, and so a global union system may have the aim of negotiation and bargaining with global companies. No such structure exists at the moment.

Global unions are currently confederations of affiliates and there are few agreements concerning basic terms and conditions. But the potential and the ideas are there. The conversation has started. We must resist the temptation to despair at this new world and seek instead to face the future.

Nigel Flanagan is the senior organizer for UNI Global Union, which represents 20 million workers from over 900 trade unions in the skills and services sector.

This is an edited version of a story that originally appeared in Morning Star.