“Extra, extra! Read all about it!”

This iconic, almost timeless callout was typically accompanied by the sight of a ramshackle newsstand providing, sometimes but not always, the strongest cup of coffee and the most recent happenings with copies of every local and national newspaper in print on the day.

So common a scene, for those of us who can remember, it became part of our cultural heritage. We’ve seen and heard it mimicked on cinema screens countless times. Who hasn’t heard of the “Newsboys?”

Local newspapers, provided daily by dedicated staff, gave us insight into the activities of the world around us and provided readers an opportunity to better understand and balance out political thoughts and opinions. They created opportunities for dialogue during election season and forced us to sit, read, and absorb information away from shiny distractions.

But the local paper is dying; in many places, it’s already dead. Struggling for years against the power of television, declining print ad revenues, and the advance of a technological world where click counts determine value, the remaining local and regional newspapers are in a fight for survival.

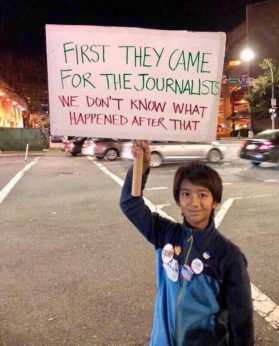

If COVID-19 doesn’t get them, capitalist consolidation—driven by some of Wall Street’s most powerful hedge funds—will. In his book on the death of the New York Herald Tribune, arguably the better paper coming out of the Big Apple, Richard Kluger wrote, “Every time a newspaper dies, even a bad one, the country moves a little closer to authoritarianism.”

In the era of mass disinformation and conspiracy theories under Trump, and the disastrous lingering effects left behind even when he’s gone, no truer words could best describe the crisis happening in the fourth estate.

But some journalists are fighting back.

Digital-driven decline

As technology has advanced, information—even bad information—became easier to obtain, and at a much quicker rate. It was no longer about who is the most accurate first, but rather, who reports it first. This privileged bigger national outlets—first on television and then online.

The usual advertisement business model that kept the presses rolling slowly dried up.

As with so many other American industries, the real decline for newspapers began in the 1970s and continues to the present day. The digital age in particular has not been kind to print journalism. In 1985, paid newspaper circulation nationwide totaled nearly 63 million; by 2018 subscribers had dwindled to less than half that number, just over 28 million.

The hit to newspapers was felt by the big-name mastheads, the New York Times, Washington Post, et al., but the deadliest damage was inflicted on local newspapers. Thousands have gone under in recent years, leaving millions of Americans without an essential source of news and depriving local communities of a voice—preventing them from discovering political corruption, organizing among neighbors, promoting community and civic engagement, and employing their talented writers, photographers, and production experts.

There is assuredly a crisis in journalism generally and a crisis for local newspapers particularly. A 2019 report by the Brookings Institute found that over 65 million Americans live or work in counties with only one local newspaper or none whatsoever. Fewer Americans today have print subscriptions and prefer the punditry of national news—Fox, CNN, MSNBC—over local coverage of the same issues.

The separation of local journalism from the local reader has also triggered an overall disengagement in local participation within democratic institutions. The report found that in communities that have lost newspapers, fewer candidates are running for local office, and fewer citizens vote in local elections.

And as we have seen with the COVID-19 response, all politics—especially in a life or death situation—is local.

Hedge funds and media monopolies

Plunging ad buys and shrinking subscriber bases have left hundreds of local newspapers open for pillaging by corporate media monopolies and hedge fund interests.

In 2019, GateHouse Media, owned by New Media Investment Group, merged (hostile) with Gannet, whose flagship paper is USA Today, along with its 261 local papers in 46 states. And while the COVID-19 pandemic has provided convenient cover, there were certainly already plans for laying off much of the reporting staff. Coronavirus just made it easier to get away with—and fast.

Pew Research shows that from 2008 to April 2020, U.S. newspapers have cut half of their newsroom employees. Corporate consolidation has been a driving force.

“The long-term decline in newsroom employment has been driven primarily by one sector: newspapers. The number of newspaper newsroom employees dropped by 51% between 2008 and 2019, from about 71,000 workers to 35,000,” read the report.

The reaction of one local reader in Ohio to the downsizing of the Cleveland Plain Dealer shows how detrimental and brutal the death of local news can be—for journalists and the communities they serve.

“My husband and I moved back to Cleveland three years ago, and one of the first things I did was subscribe to The Plain Dealer. And now, in these critical and often scary times, I strive to support journalism, and our local journalists, in any way we can,” said Carol Kelleher, in a letter to the editor.

“But, The Plain Dealer’s recent layoffs of so many respected journalists is deeply troubling. It was mind-boggling that on the same day of editor Tim Warsinskey’s April 5 column, “Plain Dealer layoffs take place amid challenges,” the paper contained many articles by these very journalists. I get that newspapers need to balance their expenses, I really do. But, based on these layoffs, I find myself not trusting the very news source I need to trust.”

The Plain Dealer was bought out by Advance Local, one of the largest media owners in the United States, controlling news operations in more than 20 cities and reaching 50 million people.

Looking at the major Midwest paper, the Chicago Tribune, we see a clear pattern of a hedge fund takeover. Owned by Tribune Publishing—which also owns the Baltimore Sun, the Hartford Courant, and Orlando Sentinel—the Chicago Tribune was, in a sense, put up for auction to the highest shareholder bidder.

New York hedge fund Alden Global Capital showed up and began gobbling up shares of Tribune, 32% overall. That was in 2019; by January 2020, several Tribune journalists were offered buyouts, signaling layoffs were coming soon. Again, this was before the pandemic crisis broke in the U.S.

“In recent years, we and our colleagues have exposed rapes and assaults inside nursing homes, deadly hazards in children’s toys, the staggering prevalence of sexual violence in Chicago’s public schools…and rampant corruption at the highest levels of Illinois government,” wrote Tribune staffers in a New York Times opinion column. “Now, that type of journalism faces an urgent threat.”

Staffers there, represented by the Chicago News Guild—a shareholder of the publishing company—have refused to go down without a fight. The union waged a proxy campaign to block two board members representing Alden Global Capital by taking their message to the shareholders directly.

In a letter dated May 4, 2020, the union questioned the amount of experience the two Alden board member nominees had and raised questions about financial malfeasance:

“Alden has taken unorthodox actions at MediaNews Group (MNG) that should be of particular concern to the Tribune Publishing board and shareholders. As a board member of MNG, Mr. Minnetian (one of the two Alden members) bears considerable responsibility for and should answer for such actions as the investment of MNG pension monies into Alden funds, the extraction of cash out of the news operations of MNG to fund outside activities, and the opaque disposal of MNG real estate.”

It was a valiant and bold move by the union, but on May 21, Chicago Tribune shareholders voted to keep the Alden board members seated anyway.

Save the News

While the Tribune affair is undeniably disappointing, there is reason to look beyond all the feelings of doom and despair. Far and wide, the attacks on journalism—going all the way up to the Trump White House—have led to an increase in union organizing in the media sector. There are thousands of journalists primed to challenge those who wish to see the independent, watchdog nature of their profession destroyed.

In response to the continued attacks against a free press, and the handling of the COVID-19 pandemic, the News Guild, part of the Communication Workers of America, recently launched a “Save the News” campaign urging the immediate allocation of COVID-19 relief funds to sustain local journalism during crisis.

The union’s campaign “will involve a six-figure digital ad campaign, direct lobbying on Capitol Hill,” and a new website where furloughed or laid-off journalists can tell their story, giving the public a raw perspective of life as a journalist.

The NewsGuild also has a three-part federal relief plan which calls on Congress to:

-

Provide direct grants to workers to subsidize the incomes of employees at local print and online news outlets;

-

Expand access to the Small Business Administration’s Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) for local news outlets that currently may be ineligible because they are owned by larger companies; and

-

Direct federal spending on community outreach advertising to local newspapers to replace lost revenue.

“I am humbled to see so many members of our industry unite under one cause: protecting local journalism,” Jon Schleuss, president of the NewsGuild, in a statement. “Americans need access to information about their local communities more than ever, and yet layoffs and furloughs are only increasing as this pandemic continues. Congress needs to act to save the news before it’s too late.”

To learn more, and take action to #SaveTheNews, click here.

The author is a member of the Chicago Newspaper Guild, Local 34071—TNG-CWA