Born on Dec. 12, 1943, in St. Louis, Wilkerson was the oldest of ten children. He attended Sumner High School, where he was a member of the student council. He was also a member of the Spirit of St. Louis Drum and Bugle Corps, where he played the baritone horn. It was at an early age that Wilkerson developed a love for jazz and blues. According to his daughter, Lisa, “he could cut a rug.”

An avid reader, Wilkerson’s first post-high school job was at the St. Louis Central Library as a circulation department clerk, where he quenched his thirst for knowledge.

As his daughter recalled, “He seemed to know something about everything. He deepened his understanding of the national struggle for racial and economic equality and began to commit himself to the movement.”

It was during this time that Wilkerson joined the St. Louis NAACP Youth Chapter and the St. Louis Chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). He also began walking the picket line at the now historic Jefferson Bank protests, one of the most important chapters in St. Louis civil rights history. In 1963, African Americans activists launched a series of protests against Jefferson Bank due to its refusal to hire Black employees; they also saw the bank as exemplifying the widespread racist hiring practices used by major companies throughout the city.

Later, the protests moved to the downtown Scruggs, Vandervoort, and Barney stores, where Wilkerson was arrested and jailed for civil disobedience.

By 1966, Wilkerson had joined the IUOE Local 513, becoming that union’s first Black apprentice; he graduated in July 1970 as a construction crane operator. In and out of Local 513, he broke down barriers for generations of Black trade unionists for decades to come.

Wilkerson was part of a larger nationwide movement against racism and for equality within largely white skilled trades, and by 1967, he had joined the St. Louis Chapter of the Black Labor Council. During this time, African Americans were often excluded from AFL-CIO Central Labor Councils. By 1972, the Black Labor Council officially merged into the Coalition of Black Trade Unionists (CBTU), of which Wilkerson was a founding member.

Wilkerson also worked with other Black trade unionists, local elected officials, and Communist Party members to found and build the Organization of Black Construction Workers. The organization’s goal was to help more African Americans get into skilled trade jobs and to support African Americans fighting racism on the job site.

During this time, Wilkerson officially joined the Communist Party USA. He would remain a member of the party for the rest of his life, serving as its Missouri / Kansas District Organizer for many years.

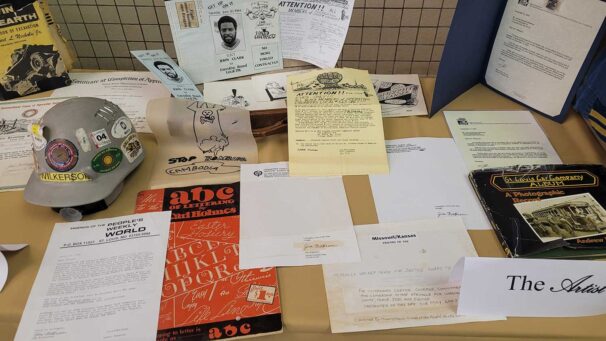

Inspired by Ollie Harrington, famed African American political cartoonist who moved to the German Democratic Republic and contributed to Wilkerson’s favorite newspaper – the Daily World – Wilkerson often designed leaflets, fliers, brochures, and campaign literature.

According to Lew Moye, President Emeritus of the St. Louis Chapter of CBTU, Wilkerson “was grounded in the working class. He never lost sight of that. The working class was his North Star.”

Wilkerson was also an internationalist; he often joked about reading Soviet Life while on the clock sitting in a construction crane. During the 1980s, Wilkerson, along with other CPUSA and CBTU members, such as 22nd Ward Alderman Kenny Jones, worked to divest St. Louis City pension funds from apartheid South Africa.

Wilkerson married his first wife, Geraldine, in August 1969; they had a daughter, Lisa. After 23 years of marriage, Geraldine passed away. Wilkerson married Laura Francis in August 1998, and he remained a loving and loyal family man, trade unionist, and comrade until his passing on Oct. 1, 2024.

To fellow CPUSA leader Zenobia Thompson, “he exemplified working class values in every area life.”

After he retired as a crane operator, Wilkerson developed Parkinson’s disease. Though his ability to participate in protests and rallies diminished, he was still a regular fixture at the monthly CBTU meetings, and local CPUSA members organized “Red ’til I’m Dead” club meetings at Wilkerson’s house.

In 2010, Wilkerson received the Hershel Walker Peace & Justice Award from Missouri / Kansas Friends of the People’s World in recognition of his lifetime commitment to peace, equality, workers’ rights, and socialism. Hershel Walker was a long-time St. Louis CPUSA leader and mentor tragically killed in a car accident while on his way to deliver petitions to save jobs at the Chrysler plant.

Last year, at its 50th Anniversary Gala, CBTU also honored Wilkerson for his lifetime commitment. Lisa Wilkerson read some prepared remarks on Jim’s behalf: “He emphasized the ‘collective fight’ to defeat so-called ‘right-to-work’ in 1978, to end apartheid in South Africa, and to free the ‘Wilmington Ten’ – nine young men and a woman who were wrongfully convicted in 1971 in Wilmington, N.C., of arson and conspiracy.”

To the very end, Jim Wilkerson believed in the power of collective action by everyday working-class people. He exemplified this belief throughout his life.