LOS ANGELES—Politics collide with art, terror, and rich helpings of morbid comic relief when “Father of the People” Joseph Stalin and Soviet Cultural Minister Andrei Zhdanov summon the Soviet Union’s two most eminent composers, Sergei Prokofiev and Dmitri Shostakovich, to the Kremlin for a vodka-fueled “music lesson.” The occasion is the night of the first day’s session of Moscow’s infamous Composers Congress in 1948, gathered to denounce “formalism” in art and to reorient composers toward their duty to the people—to write uplifting, harmonious and hummable, optimistic melodies as both comfort after the horrifying losses of World War II and as inspiration for the socialist post-war rebuilding. No more of this “art for art’s sake.”

Odyssey Theatre Ensemble founding artistic director Ron Sossi directs Stalin’s Master Class in his second essay at the play: He first staged it 37 years ago, not long after the play was written, curiously enough with the same actor (Randy Lowell) playing Shostakovich whom we see today.

Odyssey Theatre Ensemble founding artistic director Ron Sossi directs Stalin’s Master Class in his second essay at the play: He first staged it 37 years ago, not long after the play was written, curiously enough with the same actor (Randy Lowell) playing Shostakovich whom we see today.

“I’ve always been fascinated by the nature of so-called ‘evil people,’” Sossi explains. “What makes them tick? Do they see themselves as evil, or do they see themselves as doing the right thing? In Master Class, you see a side of Stalin that is very patriotic, a man who wants to resuscitate his country. He wants to get these guys to write music that is more accessible and comforting to the sad survivors of the devastating World War, the children, and the old people. The play is very funny, which some might find disturbing, and there’s a lot of great music, all played live. Get ready for a big musical surprise at the end!”

In Andrew Child’s interview with Sossi in Broadway World, Sossi continues: “It is easier today for audiences to draw relationships between Stalin and the strongman figures they see in the news every day. From Putin, to Netanyahu, to Trump. I don’t remember them existing as obviously as they do now when we did this play before.” He might have added India’s Modi, Hungary’s Orban, El Salvador’s Nayib Bukele, and readers can fill in some further blanks.

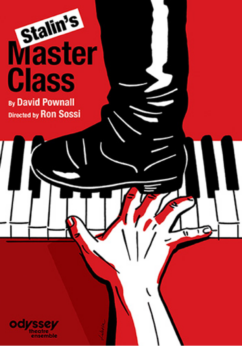

The play was originally called Master Class, but there is another play by that same name, by the late American playwright Terrence McNally, about Maria Callas. The newly dubbed Stalin’s Master Class is by David Pownall (1938–2022), an award-winning British novelist and playwright who had over 80 radio plays broadcast on the BBC and worldwide. His work for the stage has been produced in many countries throughout the world, Master Class itself, written in 1983, having been translated and performed in some 20 languages. Of all his work, Master Class was his best-known play. He wrote the book Writing Master Class as an account of the inception and development of the play, interspersed with twists of his own life story.

I don’t know much about Pownall beyond what’s in his obituary. But there are some telling details about his life that I believe impact this play. For a decade, most of the 1960s, he lived in Zambia working for the Anglo-American copper mine. Zambia is the former British colony of Northern Rhodesia until Zambia established its independence in October 1964. (Southern Rhodesia became Zimbabwe.) So, if it is not too presumptuous, we may expect that Pownall might have looked with a certain favor upon the British Empire. The USSR and its allied socialist states devoted exceptional energy toward encouraging, educating and even arming the anti-colonial resistance against European powers such as the UK, France, Belgium, and Portugal.

The second hunch I have about this play (without having read the author’s memoir) is the period in which it was written. By 1983 the fiercely anti-Communist Ronald Reagan was in his first term in the White House. That was the year he sent U.S. troops to invade the tiny island nation of Grenada to rid it of its left-wing, Cuba-friendly leadership. His close colleague in the UK, the Right Honorable Baroness Margaret Thatcher, was well settled into her long tenure (1979-1990) as Prime Minister. If art and culture are reflective of their time and place, well, 1983 would be the right time for an unrelenting attack on Communism as an idea, and what better piñata to bash than the 30-years dead Joseph Stalin?

Still, old and important questions must be asked. Generally speaking, the superstructure of a society (the educational system, housing, religion, arts, culture, etc.) mirrors and upholds the values of the dominant class—capitalist, socialist, whatever. In a “free,” i.e., capitalist society, we are taught, that artistic expression cannot be forced to conform to political ideology. Yet there are other ways of erasing, marginalizing, and suppressing certain artists—blacklists, prison, harassment, firing, denying tenure, awards, living expenses and press coverage, censorship, book banning, deportation, and more. To make the point, let me simply ask, has The New York Times ever reviewed a book issued by International Publishers?

In Pownall’s dark satire, Prokofiev (Jan Munroe) and Shostakovich are subjected to the ranting and bullying of Stalin (Ilia Volok) and Zhdanov (John Kayton), who accuse them of “formalist” musical tendencies that are alien to the Soviet people and their artistic tastes. “Music that could make a whole population sick!” And under threats to their very lives (the word “liquidate” comes up more than once), they do wind up conforming. The year 1948 (Jan. 13) also saw the murder of Soviet Yiddish actor and artistic director of the Moscow State Jewish Theater, a former chairman of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee during World War II, as the beginning act of Stalin’s obsessive anti-Jewish campaign. Surely, both Prokofiev and Shostakovich had reason to tremble for their fates.

It was around this time that Paul Robeson visited the Soviet Union and inquired about his old friend, the Yiddish poet Itzik Feffer (1900-1952). Assuring Robeson that Feffer was just fine, the Soviets dragged him out of prison, dressed him up, and they met in a (bugged) hotel room. When Robeson asked how things were, Feffer, knowing he was being recorded, simply drew a sharp horizontal line across his neck, which said all that Robeson needed to know.

This gave rise to what some on the left call “the Robeson dilemma,” though it was hardly peculiar to Robeson alone. Should he have come back home and told all he knew about the Soviet terror? Or would that have placed him in the imperialist camp in the Cold War, detracting from the Soviets’ own reconstruction and advancement, and from their enormous efforts on behalf of the struggling, still colonized so-called Third World?

There were echoes of the anti-“formalist” Inquisition in all the Communist Parties, including in the U.S., involving such leading artists as Albert Maltz and, more quietly, composer Marc Blitzstein, who left the Party in the late 1940s precisely over the question of being told what and how to write.

As a matter of biographical curiosity, it’s interesting to note that Stalin and Prokofiev died on the same day, March 5, 1953.

In an era when books are being banned from libraries, and the history of race relations in America, the contributions of immigrants to our history, sex education, and modern settled notions of science, all are being attacked, the issues raised in Stalin’s Master Class remain painfully germane.

The meeting imagined in the play never actually took place, though the composers’ conference and other events referred to are factual. The terror the two composers experienced was quite real, as many biographies and memoirs attest.

The acting is so convincing, so sure-footed, so vivid. I don’t doubt for one minute the essential premise of the play.

Yet I do believe that owing to the prejudices and sentiments of his time (and many other times both earlier and later) Stalin is not given his due, both historically and—for the purposes of a theater review—theatrically.

Historically, I mean, the playwright shows no empathy whatsoever with the challenges of rebuilding after such a holocaust (and I do use the word intentionally) that befell the Soviet lands. (By the way, speaking of that word, the Soviets did more—way more—than any other nation to save European Jewry.) By 1957 the Soviets were launching Sputnik! Stalin was, of course, a tyrant with no conscience and I hold no brief for him—other than helming the Soviet Union as the world’s most significant counterforce against the Nazis and rescuing us all from fascism. By 1983, the year this play was written, billions around the world would surely have sided more favorably toward the Soviet project of socialism—however, and however deeply flawed—than the globe-strutting, war-mongering imperialism, and neo-colonialism of the NATO community.

And theatrically, one thinks of the great tragic figures of the stage—Oedipus, Elektra, Lear, Othello, Boris Godunov, even proletarian figures like Willy Loman—and they are entitled to their greatness, their nobility even, before their hubris, or their madness, catches up with them. The only sympathy Pownall shows for him crops up when Stalin, recalling his youth as Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili, remembers how his superiors at the seminary would not permit him the use of his native Georgian language and also forbade his recitation of verses by Georgia’s national poet Shota Rustaveli or singing old Georgian folk songs. Combined with the effects of his copious draughts of vodka throughout the evening, these passages show Stalin as merely a resentful drunk who has amassed unimaginable power and uses it ruthlessly. It surely makes for better theater when you have at least a little sense that under the right circumstances, you could possibly, perhaps even remotely, identify with the protagonist.

Having said that, it got me thinking about Stalin’s view on the national question, which helped define the Soviet approach to this all-important issue in a nation of 15 republics and a large number of so-called “autonomous” regions, each one of them with multiple languages spoken. In short, a larger context for us to understand this man beyond simply starting with the inalterable premise of his essential evil would have made for a stronger play without our losing the author’s point.

Perhaps this is, in part, what Andrew Child was getting at, concluding his interview with the director, “Sossi slyly wonders if, upon hearing the cacophonous compositions included in the play, some audience members may side with the fictionalized version of Stalin, desiring the pianist to play a more tranquil, familiar sound. It will be interesting to see what else audiences find agreeable in this humanized Stalin.”

I am reminded of an incident back in the mid-1980s when I was working in New York as publicity manager for the musical publishing firm of G. Schirmer, which handled the U.S. rights of the Union of Soviet Composers. I invited my dear friend Betty Millard, a prominent Communist from the late 1930s to the mid-1950s, to accompany me to Carnegie Hall for the American premiere of a new work by a Soviet composer now that the Zhdanov rules no longer applied, and composers were engaging in more experimental forms. At the end of the piece, which I admit was somewhat hard on the ears, she remarked, “You see, now that the Soviets allow composers to write whatever they want, they write music we in the West can’t stand either.”

Well, clearly, there’s much more that could be said on this topic.

The acting is superb, and the absurdist Kafkaesque twists Pownall puts his characters through are the height of theater. I was especially happy to catch up with Ilia Volok, whom I appreciated in last year’s Yaacobi & Leidental. Despite my reservations, because of the quality of the production, and for its astute considerations on the theme of artistic freedom and the role of art in building a healthy, workable society, not to mention for the historical edification, the play should rate very high on any theatergoer’s list.

With the absolutely terrific piano playing by music director Nisha Sue Arunasalam, we are almost totally convinced that the actors—all of them in turn—are actually playing the battered Blüthner on stage, whereas only Lowell (Shostakovich) does his own playing. The scenic design is by Pete Hickock; lighting design is by Jackson Funke; sound design by Christopher Moscatiello; costume design is by Mylette Nora; props design is by Jenine MacDonald; and graphics design is by Luba Lukova. The stage manager is Jennifer Palumbo. Beth Hogan produces. Stalin’s Master Class is presented by the Odyssey Theatre Ensemble in association with Isabel and Harvey Kibel.

Performances of Stalin’s Master Class take place on Fri. and Sat. at 8 p.m. and Sun. at 2 p.m. through May 26. There will be two additional weeknight performances, on Wed., April 17 and May 15, at 8 p.m. Post-performance discussions are scheduled on Fri., April 26, Wed., May 15, and Sun., May 5. Every Fri. is “Wine Night”: enjoy complimentary wine and snacks and mingle with the cast after the show.

Tickets to performances range from $20-40 on Wed., Sat. and Sun. Performances on Fri. are Pay-What-You-Can (reservations open online and at the door starting at 5:30 p.m.). The Odyssey Theatre is located at 2055 S. Sepulveda Blvd., Los Angeles 90025. For more information and to purchase tickets, call (310) 477-2055 or go to the Odyssey website.

We hope you appreciated this article. At People’s World, we believe news and information should be free and accessible to all, but we need your help. Our journalism is free of corporate influence and paywalls because we are totally reader-supported. Only you, our readers and supporters, make this possible. If you enjoy reading People’s World and the stories we bring you, please support our work by donating or becoming a monthly sustainer today. Thank you!