LOS ANGELES — “I don’t photograph anything that doesn’t move me. Whatever you are translates to your photos, therefore start from the heart,” says the globetrotting photographer Adger Cowans. His work, along with that of his fellow members of Kamoinge, a Black photographers’ workshop founded in 1963 that gathered some 14 artists together, is currently on view at the J. Paul Getty Museum. Born in 1936, Cowans is the oldest member of the group and has been their president for the past ten years. Kamoinge, incidentally, is not purely a historical phenomenon: it is still functioning 59 years later, making it the most durable group in the history of photography!

The show of two hundred black and white photographs is entitled Working Together: The Photographers of the Kamoinge Workshop. “Kamoinge” (kuh-moyn-gay) comes from the Kikuyu people of Kenya and translates as “a group of people acting and working together.” In the 1960s, they viewed black and white as the supreme art, dismissing color photography as belonging to the commercial world.

Born in Columbus, Ohio, Cowans got his B.A. in photography from Ohio University and later attended the School of Motion Picture Arts and School of Visual Arts in New York. After a stint in the Navy, he moved to New York and got to know Gordon Parks, who was on the staff at Life Magazine as its first African-American photographer. Parks was impressed with Cowans’s portfolio and took him on as his assistant.

Given the Jim Crow era in which Cowans grew up and matured, “I took all that racism and rejection and everything,” he told NPR interviewer Ryan Caron King, “and I put it in my work. One of the big things I learned from Gordon Parks was to take negative energy and turn it into positive power.”

Cowans also enjoyed a Hollywood career as a still set photographer, working with directors such as Spike Lee and Francis Ford Coppola, taking candid shots of actors in rehearsal and between takes for publicity and continuity.

Although professionally employed for decades, widely exhibited, and the winner of a number of awards and fellowships, it was not until he was 80 that he approved the first large-format edition of his work. In an appreciation of this volume, Personal Vision, a lifelong friend, Peter Lownds, wrote:

“Adger is a camera-slinging griot, the Sonny Rollins of the Leica. He travels widely when being still.”

A perennial wanderer, Cowans spent long periods of his life abroad—Suriname, Brazil, Mexico, Morocco, Italy, and elsewhere by vocation and location.

The Kamoinge exhibit opens a window on the world of Black photographers in troubled times. When newspapers and magazines that did not employ African Americans went into Northern ghettos they saw out-of-control rage where Black photographers saw determination and courage. Where white-owned media showed masses of Black people gathered together as a threat to organized society, Black photographers and writers saw an oppressed minority courageously demanding their dignity and equal rights as citizens. Where white photographers traveled to the Global South and saw poverty, malnutrition, and slums, Black photographers and cinematographers understood the drama of newly minted citizens struggling to build and support independent nations in the shambles left by centuries of extractive colonialism.

Though many of Kamoinge’s images grate against the received notions of American democracy, not all their work is narrative. Some images are visual poetry, numinous shapes captured on the streets or in the studio and manipulated in darkrooms to create a mood, a statement, a tribute, a landscape.

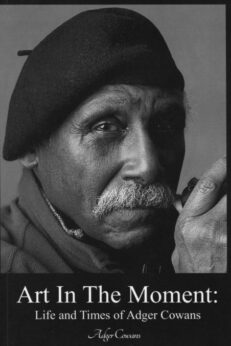

A few years back, Lownds got Cowans to sit down and tell his story. The result is a 113-page book, Art in the Moment: Life and Times of Adger Cowans. While this is not the full-bore scholarly biography a major artist of his stature merits and may one day receive, it is still an important source of information and perspective on art, life, and times—not surprisingly all three of those words are featured in the title. Cowans’ childhood memories, growing up during World War II, are especially poignant.

The book does not follow a specific chronological course, and it is sometimes hard to piece together the sequence of Cowans’ romantic involvements and travels. Yet there is considerable wisdom, charm, and social history here as the photographer enlists in the Navy, digs the NYC jazz scene, and breaks the color line in the Still Set Photographers Union. Adger ventures abroad, takes pictures of people, ordinary and illustrious. He is a Renaissance man in the 20th century.

About some of his family history, with a claim that is backed up by the Wikipedia entry on the subject: “Grandpa was quiet and reserved. He worked on the Pennsylvania Railroad as an oiler. A black man, Elijah McCoy, invented a system whereby machines could be oiled while in use that revolutionized industry, that’s why ‘the real McCoy’ became a synonym for anything authentic.”

About how he was introduced to the medium of photography from his Mama’s albums: “Her aunts and uncles, new babes in arms, my Uncle Wilbur’s first girlfriend, Mama’s first dog and cat, pictures of flowers my mother admired, wintertime pictures, changing seasons, picnics, weddings, family occasions of every sort. On days when it was raining or I was bored, I’d pull my mother’s albums out and look at them. She must have had eight or nine books like that, filled with pictures. Each album contained four or five hundred pictures. They weren’t just pictures she took, she collected other family members’ photos as well. Everybody collected pictures back then. Kodak made America a picture-taking society because anyone could shoot a picture, anytime, anywhere, much like they use cell phone cameras today.”

On his early visual training: “When I was small, I played the part of Baby Jesus. One of the actors would lead me onstage by the hand. My head would be wrapped in a colorful cloth turban and I wore a little white robe. As I got older, I became one of the shepherds in the field. Our silhouettes were projected on a backdrop by a low-angled spotlight. In retrospect, I realize that my photographer’s eye was being trained from the start.”

The young man with a paper route got hooked on photography and purchased his first mail-order camera with money “borrowed” from his father. Out of the Christmas tips he received from his loyal customers, Adger paid his father back the $40. Later on, after his first job in New York, Adger returned home to see his father in the hospital and handed him $250.

“He looked at the money, then he looked at me.

“‘Where’d you get this money?’

“‘From taking pictures.’

“He shook his head in wonder: ‘Mm-mm-mm!’ I could sense his pride in me. That was the last time I saw him alive.”

About art: “When a jazz musician plays his concept of a tune, it has a living presence or essence that cannot be duplicated. After it’s done, you can think about it and attempt to recreate it. That’s what the majority of what is commonly considered ‘art’ accomplishes. It recreates the past.”

“If I come back in another lifetime, I still want to be an artist. There’s no other life for me. I want to be a translator of the spirit, a doorway, a conduit for the ineffable.”

“What I’ve learned in all my wanderings is that all humans carry the same blood. We all hurt, live, love, and die. The only difference between the average person and the artist is that the artist is in touch with his or her inner voice. Listen to and express the musings of your inner voice. When you do something good for another person, it flows back to you and you feel good. When you do something hurtful, you feel that too.”

Personal Vision was published in 2017. Lownds bought a copy and recognized the passionate pilgrim in Cowans:

He is dedicated to keeping track of life,

mindful of cities, rain, horn players, trees,

light and shadow, mothers and sons, beautiful

ladies, handsome men, singers, musicians, painters

composers—you name them, he knows them, spends

time with them, celebrates their talent, immortalizes

their humanity.

Other photographers included in the Getty exhibition include Ming Smith (the only woman in the group, who joined it in the early 1970s), C. Daniel Dawson, Anthony Barboza, Louis Draper, Herb Robinson, Albert R. Fennar, Ray Francis, James M. Mannas Jr., Shawn Walker, Herbert Randall, and Roy DeCarava.

An 82-minute video, The Illustrious Career of Adger Cowans, can be viewed here. In conjunction with that same exhibition at the Fairfield University Art Museum in Connecticut, NPR did a three-minute interview with the photographer that can be heard and read here.

Working Together: The Photographers of the Kamoinge Workshop is currently on view at the J. Paul Getty Museum, 1200 Getty Center Dr., Brentwood (Los Angeles). The museum is open Tues.-Sun., through Oct. 9. Admission is free but they charge for parking. It is accessible by public transportation. For more information, call (310) 440-7300 or go to getty.edu.

Art in the Moment: Life and Times of Adger Cowans

Art in the Moment: Life and Times of Adger Cowans

By Adger Cowans as told to Peter Lownds

Beverly Hills: Noah’s Ark Publishing Service, 2018

ISBN: 978-1-7321325-3-5