“It’s not only not going to get better. It’s going to get worse every day.”

When he uttered those words at the Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) in Washington on February 23, top Trump advisor Steve Bannon was talking about the coverage of Trump administration policies by the press, which he still insists on rather un-affectionately referring to as “the opposition party.”

However, he may well have been describing the prospects for preserving the democratic character of American government – particularly American public administration.

In a joint appearance with White House Chief of Staff Reince Priebus (video), Bannon ruminated on the achievements of the Trump administration’s first 30 days and waxed poetic about how, contrary to news emerging from the Washington rumor mill, he and Priebus actually get along swell.

As chair of the Republican National Committee before being picked by Trump for the chief of staff role, Priebus is seen by many as one of two power centers supporting the president. He represents the establishment wing of the GOP – the party bigwigs and the Washington class. Bannon, meanwhile, as former editor of Breitbart News – “platform for the alt-right” – is the ideological guardian of the far-right nationalist and populist side of the Trump coalition.

There were many points in their presentation which should arouse interest, such as Priebus’ excitement that the confirmation of Supreme Court nominee Neil Gorsuch would cement Trump policies in place for a long time to come: “We’re not talking about a change over a four-year period. We’re talking about a change of potentially 40 years of law.”

But it was Bannon’s discussion of the key principles shaping policy development in the Trump government that were most illuminating. Describing what he called the “three buckets” of administration priorities, Bannon reinforced the focus on concepts like sovereignty, national rebirth, and authority that are key parts of the economic nationalist agenda.

Perhaps his most revealing lines, however, were those concerned with something he kept referring to as the “administrative state.” He said that all of Trump’s cabinet appointments were “selected for a reason…deconstruction of the administrative state.”

What exactly is the administrative state and why are ideologues like Bannon so determined to see it destroyed?

The Administrative State

The term “administrative state” is a somewhat obscure one outside the circles of political science and public administration scholars. Taking advantage of this obscurity, Bannon tried to set the terms of debate and provided his own understanding of the concept:

“Every business leader we’ve had in is saying not just taxes, but it is also the regulation… the way the progressive left runs, if they can’t get it passed, they’re just gonna put in some sort of regulation in…in an agency. They’re all going to be deconstructed and I think that’s why this regulatory thing is so important.”

Matt Schlapp, chairman of the American Conservative Union which hosts CPAC and moderator of the Priebus-Bannon talk, joined in, saying, “We’re promulgating more laws and regulations than we ever had before. And most of that are from these independent agencies that are just on autopilot.”

The image one gets of this administrative state from such explanations is of un-elected left-wing bureaucrats who are out of control and running roughshod over business and the American people. When Democrats can’t win in elections or get something through Congress, they use their bureaucratic power to slip things in through regulation.

The administrative state is presented as something subversive and anti-democratic – a way in which liberals and progressives force their agenda on a public that did not vote for them.

The original notion of the administrative state was actually the exact opposite.

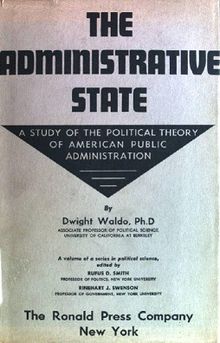

Dwight Waldo, a professor and former government price control official, first coined the term administrative state in 1948. He asserted that the orthodox notion of bureaucrats who just mindlessly follow orders from the top – a detached, supposedly “scientific” system of administration – was actually incompatible with democracy.

Instead of just being cogs who carry out policy directives without thought, Waldo believed that public servants should be informed, active agents of change dedicated to improving people’s lives and strengthening democratic participation.

There were a few principles that were central to Waldo’s notion of the administrative state. He believed the tension between democracy and bureaucracy gave those who work in government the duty to put protection of democratic principles over everything else. Openness and the participation of the people in the development and implementation of policies that affect their lives were paramount.

Bureaucrats had a responsibility to serve the public, not just their political masters. In political science terminology, he rejected the notion of a politics/administration dichotomy which saw the state as simply the instrument of whoever held elected power. Calls for “efficiency” by those in authority should never be allowed to override rule of law, due process, and transparency.

Perhaps Waldo’s most important maxim was that government cannot be run like a business. Democracy, the Constitution, and public interest require adherence to higher criteria than simply watching out for the bottom line or following orders. This implied that public servants had to think for themselves and consider the impact of what they were asked to do by policymakers. How does it affect people’s lives? How should it be implemented?

One of Waldo’s colleagues said that due to his work, the profession of public administration “took a strong stand on humanistic administration by committing to…focus on serving the public. That meant literally getting into the streets and taking an active role.”

The De-Regulatory State

With its shock-and-awe campaign of rapid-fire executive orders, policy guidance memoranda, and of course the directive to drop two regulations for every new one implemented, the Trump administration is so far showing a commitment to a notion of government very different than the one put forward by Waldo.

Demanding adherence to presidential authority and extreme loyalty on the part of cabinet secretaries and other officials, the White House certainly appears to view the entire American government as an instrument to be wielded by the man at the top.

Bureaucrats won’t obey? They are shown the door. Courts won’t validate decisions? Then they must be headed by “so-called judges.” In one short speech, Bannon sweeps them all aside as elements of a nefarious administrative state.

The striving for authority and unrestricted executive power goes against the democratic and human rights sensibilities that were actually at the heart of Waldo’s notion of the administrative state. War is Peace. Freedom is Slavery.

In his unsophisticated attacks on the administrative state, Bannon is helped intellectually by the work of think-tanks like the Heritage Foundation (which has provided the blueprints for many areas of Trump policy). They publish claims that the “growth of the administrative state can be traced, for the most part, to the New Deal (and subsequent outgrowths of the New Deal like the Great Society).” In this, they are partially correct.

However, while Heritage focuses on making a conservative argument for limited government, Bannon joins in the attack against the social democratic content of the New Deal and goes beyond it to push for a more executive-centered state.

Here, the crusade of run-of-the-mill conservatives to roll back government and the welfare state merges with the authoritarian nationalist agenda of ideologues like Bannon.

The fight against regulation and public control over things like safety conditions in the workplace, fair wages, exposure to toxins, environmental protection, or what bathroom transgender students can use – all of these get simplified and packaged up into the bogeyman called the administrative state.

Demonize those who write and enforce regulations as un-elected and un-democratic, and you can de-legitimate the things they have done in the public interest. That appears to be the goal of Bannon’s pronouncements of “deconstruction.”

Of course few would argue that every regulation or administrative rule has a positive impact or serves the public interest. There are plenty of instances of bureaucratic failure and abuse of power. But the bigger principle of who public officials serve – the president, the people, or both – is what is actually at stake.

Bannon is making the case that government exists to carry out the orders of the president that the people have elected. The essence of the administrative state ideal that he attacks is that government exists to serve the public interest – and that may not always align with the commands handed down from the White House.

It’s an old public administration debate that has resurfaced in the most politicized and propagandistic of terms. Bannon has stated his position. The Trump administration, he says, is “a new political order.” It will be up to the American people to decide – at the ballot box eventually, and in the streets and town halls for now – which view they hold dear.

Comments