In Sacramento, California, on March 18, police bullets killed Stephon Clark, an unarmed Black man. The police misbehaved, but the real culprit was racial hatred, evident recently in a continuing wave of police killings of mostly Black men.

Stephon Clark died. As did Black people who died at the hands of Ku Klux Klan raiders during the Reconstruction era (see Eric Foner’s Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution). As did thousands of Blacks lynched over the course of decades, as did individuals and families killed by white people in dozens of massacres between Reconstruction and the 1920s. (Lynchings and massacres are listed and/or described at these internet sites, here, here, here, and here.)

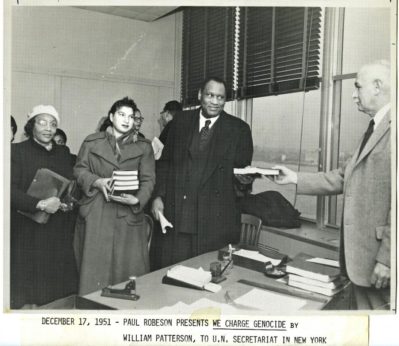

Potential victims—terrorized—sought relief. On December 9, 1948, the UN General Assembly approved its “Convention on…the Crime of Genocide.” Responding, the Civil Rights Congress in 1951 delivered to the General Assembly a 240-page petition authored by William L. Patterson. Its title was: We Charge Genocide: The Crime of Government Against the Negro People (available from International Publishers).

The petitioners condemned the United States for “mass murder of its own nationals” and for “institutionalized oppression and persistent slaughter of the Negro people in the United States on a basis of ‘race.’” They cited as evidence “thousands of Negros who over the years have been beaten to death on chain gangs and in the back rooms of sheriff’s offices, in the cells of county jails, who have been framed and murdered by sham legal forms and by a legal bureaucracy.”

The petitioners condemned the United States for “mass murder of its own nationals” and for “institutionalized oppression and persistent slaughter of the Negro people in the United States on a basis of ‘race.’” They cited as evidence “thousands of Negros who over the years have been beaten to death on chain gangs and in the back rooms of sheriff’s offices, in the cells of county jails, who have been framed and murdered by sham legal forms and by a legal bureaucracy.”

Terror and killings represent only one aspect of a system of racial oppression manifesting in the United States first as occupation of Native lands and as slavery. But oppression has assumed many forms. They include efforts taken to ensure less than decent lives for black people. Poor schooling for black children is one of them. The recent death of Linda Brown of Topeka, Kansas, on March 25 served recently as a reminder.

Brown was the lead plaintiff in the famous Brown v. Board of Education case which concluded on May 17, 1954. That day the Supreme Court ruled that racial segregation of public education is illegal. Separate schools, it reasoned, make for inferior education. Hopes were raised, but then came disappointment. Today, U.S. schools remain segregated by race. And educational outcomes for black students lag in comparison with those of white students.

It’s clear, therefore, that a system of racial oppression and race hatred has prevailed throughout U.S. history. Its staying power calls for explanation. Historian Gerald Horne offers insights.

In his Apocalypse of Settler Colonialism, published this year, Horne looks at 17th-century English colonial history. He explores political changes within that nation and problems associated with the exploitation of colonies in the Caribbean and North America.

The “Apocalypse” Horne speaks of is an ongoing one that along the way afflicted the United States at its founding—and beyond.

Colonial authorities faced difficulties. Rebel frontiersmen led by Nathaniel Bacon, for example, attacked Virginia’s colonial governor in 1676. They complained he’d left them vulnerable to Indian attacks and limited their access to Indian land. Accordingly, they attacked the Indians and occupied land.

Enslaved and dispossessed peoples resisted. An Indigenous uprising known as King Philip’s War brought chaos and bloodletting to New England in 1675-76 and later. Victorious settlers arranged for 500 captured Indigenous to be “sold into slavery from Plymouth.” Slave rebellions occurred in Barbados and particularly in Jamaica, the island England stole from Spain in 1655.

Horne notes that “Enslaved Africans constituted two-thirds of the total migration into the Americas between 1600 and 1700.” In the Caribbean, the “colonial elite could not untie the Gordian knot of bringing in more Africans to produce immense wealth while preventing them from rebelling and taking power—which finally occurred in 1791 in what became Haiti.”

In response, many Caribbean settlers moved to the mainland. Colonial authorities experimented “with providing more benefits—combat pay—to poorer settlers.” Marginalized white settlers were granted access to land. Increasingly, the exploiters used indentured servants and other poor whites to oversee slaves at work.

Clearly, those in charge were panicked. Indeed, “massive slave revolts” revealed “the frailty of the colonial project.” And “the mainland’s productive forces were advancing, while those of the Caribbean had a foreseeable upper limit.”

Officials turned to promoting “racial solidarity” among European migrants. “The elite had devised a race-based despotism driving these recent [European] arrivals into the arms of these same elites, particularly after the poorer settlers were granted some concessions.” The colonial rulers “established a cross-class alliance between and among European settlers, who bonded on the basis of ‘racial identity politics’—that is, ‘whiteness’ and ‘white supremacy’—and [on] the basis of the looting of all those not so endowed.”

This defensive alliance took shape despite religious differences among white settlers. Horne suggests that as the 18th century progressed, their attraction to an agenda of political rights further solidified a united front.

In 1688, England’s commercial classes engineered the so-called “Glorious Revolution.” With the king’s power markedly reduced, they took charge of exploiting the colonies. The new rulers, Horne writes, “proceeded to build vast fortunes on the backs of enslaved Africans and dispossessed indigenes while shouting from the rooftops about the ‘liberty’ and ‘freedom’ they were demanding at the expense of the monarchy….

“This blatant power and money grab by merchants was then dressed in the finery of liberty and freedom as the bourgeois revolution was conceived in a crass and crude act of staggering hypocrisy.” These developments led to “fueling the revolt against London in 1776.” Horne regards the United States as “a state founded on solemn principles of white supremacy, often disguised in deceptive ‘non-racial’ words.”

“Given the grimy origins of republicanism in the Anglo-American sphere, is it any wonder,” Horne asks, “that even in today’s United States, it remains difficult to extend the full bounty of rights to the descendants of the formerly enslaved or the indigenous?” Indeed, white supremacy “had its latest expression, at least in terms of underlying premise and intent, in the United States in November, 2016.”

A new generation of historians has paid considerable attention to the capitalist nature of slavery. But in discussing racial oppression, Horne only indirectly acknowledges the role of capitalism. Nor does he dwell upon societal realities of poverty and marginalization as contributing to oppression. Nevertheless, the idea that race and social class operate together in fostering oppression is by no means foreign to him.

Thus, as he concludes his book, Horne mentions that following the crisis of U.S. slavery a “corollary crisis for white supremacy” emerged and that it was “compounded by the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, which—at least—thrust the question of class onto center stage.” The advent of the Soviet Union “helped to erode the capitalist world’s maniacal obsession with ‘race’” and to bring about “crisis for all aspects of the hydra-headed monster that arose in the seventeenth century—white supremacy and capitalism not least.”

The Apocalypse of Settler Colonialism: The Roots of Slavery, White Supremacy, and Capitalism in Seventeenth-Century North America and the Caribbean, by Gerald Horne

Monthly Review Press, 2018, 256 pp.

Paperback $25.00. Also available in Hardcover and Kindle editions.