MEMPHIS, Tenn.–The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. left behind a legacy of courage and clarity in the face of racial and economic injustice. It has been five decades since the world lost this visionary—the preeminent leader of the Civil Rights Movement—but his words and actions continue to inspire the fight for democracy and racial equality today. However, since his death in 1968, it could be argued that both his image and his analysis have been de-radicalized—spun by those who seek to water down his critiques, especially when it comes to the concepts of anti-Blackness and white supremacy in the United States.

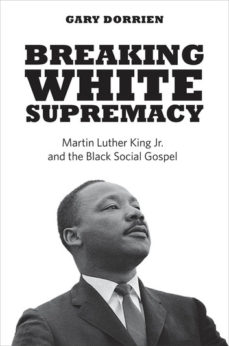

A panel at the 2018 Mountaintop Conference in Memphis on April 3 entitled, “Breaking White Supremacy: Martin Luther King Jr. and the Black Social Gospel,” sought to reverse that taming of King, clarifying his thoughts on white supremacy and relating them to our current political climate.

The Memphis gathering is a commemoration of the life and work King and is being held at the Mason Temple church. It is where King gave his last public speech, just 20 hours before being assassinated, in support of the city’s sanitation workers, who were on strike protesting low pay and poor working conditions.

It is an opportune time to put the spotlight on white supremacy in relation to King’s legacy now, as Donald Trump and his Republican Party pursue an extreme right-wing agenda that aims to do away with the progress made on civil rights, environmental justice, and the protection of working people’s standards of living—all while emboldening open racism and bigotry. The question of how the words and actions of King can be used today to combat white supremacy and bigotry was a central theme of the panel.

The featured speaker on the topic was American social ethicist, theologian, and author, Prof. Gary Dorrien. Dorrien is the author of a new book bearing the same title as the panel, which is a follow up to his award-winning work, The New Abolition: W. E. B. Du Bois and the Black Social Gospel. Dorrien’s address to the conference spoke to King’s growing radicalism in his final years and his sharp stance on anti-Blackness and its undeniable link to economic injustice. This was an aspect of King’s legacy that Dorrien insists was de-emphasized after King’s murder.

“To win the iconic status that King deserved, he had to be domesticated [after his death]—and he was,” Dorrien said. “The memory of King taking on the structure of Chicago, railing against economic injustice, denouncing the Vietnam War, emphasizing what was true in the Black power movement, and organizing a poor people’s campaign, faded into an unthreatening idealism. He became ‘safe.’ Registering as a noble idealist. The Civil Rights Movement was reduced to a reform movement for individual opportunity. But the King we need to remember is the one who understood why he was so hated [while he was alive]. King’s radicalism didn’t come out of nowhere, but from the Black social gospel,” he noted.

Dorrien asserted that King was inspired by this tradition, and carried it out in his own work. “King was steeped in the defining Black social gospel claim that the church had to deal constructively with modern intellectual criticism, emphasize the social ethical teaching of Jesus, struggle for social justice, and defy white racism,” he said.

Defying white racism, and the division it causes among working class people, was something Dorrien argues King knew was key to fighting for true democracy. “King believed that Black Americans would never be free as long as there were large numbers of poor whites,” he said. He explained that King emphasized economic justice, and he did so by pushing for the federal government to play a key role in economic reform.

One of King’s primary battles in the final years of his life, for instance, had to do with the fight for a livable federal minimum wage. Yet, Prof. Dorrien expressed that the role of the federal government in economic reform is still a “flash point” issue now, just as it was in King’s day.

“This is an issue that is felt at every level of American politics today. It is especially polarizing on racial lines, when it comes to the white working class. Poor and working-class white Americans believe by overwhelming margins that the federal government is their adversary,” Dorrien said.

Speaking to the role Donald Trump plays in this, Dorrien went on, “Trump keenly grasps onto the alienation of working-class whites and the power of racism in this country—which is why he joined the Birther movement in 2011…. Trump won the white working class by a staggering 39 percent.”

To deal with our current “political trauma,” the professor asserted that we only need look at King’s teachings to realize that “America needs to stop tolerating extreme inequality, and above all it needs to build a culture of atonement for centuries of racial violence and bigotry.” Dorrien was referencing the fact that the oppression of Black Americans has been an inherent aspect of the history of the United States since its inception. This includes slave labor, the failure of Radical Reconstruction, Jim Crow segregation, all the way up to the prison-industrial complex that disproportionately affects Black people to this day.

“Dr. King could imagine a U.S. nation that acknowledges its crimes, compels every American to learn about them in their schools, passes a reparations bill, and builds a generous, hospitable, and multi-racial social democracy. He was scathing and specific about what was needed, and what was lacking,” Dorrien stated.

Even from just the brief exploration of King’s thoughts on white supremacy and economic inequality afforded by this panel, it is clear that he concluded America did indeed have a race problem—one that persists to this day—and that addressing it was not impossible, but it did require a multi-layered strategy.

“The more that white liberals embraced Dr. King as a hero, the more vague and ambiguous he became to others still denigrated by white society,” Dorrien said. Closing out his speech, Prof. Dorrien concluded, “It became hard to remember that Dr. King was radical, militant, and angry [at injustice]…. The story of the Civil Rights Movement illuminates the trauma we are still living in. Because white supremacy, white-lash, and the struggle against hopelessness are very much still our problems today. This is what King sought to address. This is the Dr. King we need to remember.”