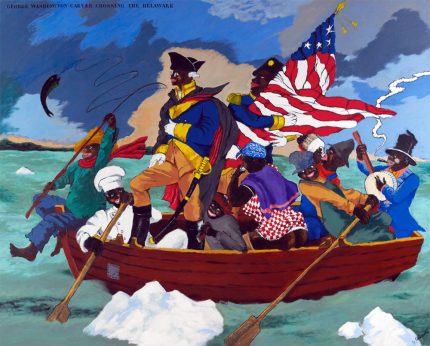

Robert Colescott’s satire of Americana George Washington Carver Crossing the Delaware has now become the centerpiece of L.A.’s new Lucas Museum of American Art. Colescott’s best known work, though, only begins to touch on his four major themes and concerns. These are: expanding Black representation in art while calling attention to the way the culture has been stereotyped in the past; a sharp critique of how the consumer products which shaped and defined him have been adapted and altered by Black experience; bringing the Black female body in all its manifestations to the foreground while commenting on the exploitation of the female body in art historical ideals of beauty; and, finally, a lampooning of the colonial legacy and a sharp cognizance of how that legacy functions in the contemporary neo-colonial world. (See Part 1 of this essay here.)

In the 1970s Colescott broke free from the de-politicized abstract tradition, the establishment of which is described in my book Cold War Expressionism: Perverting the Politics of Perception. His goal was, as he put it, “to interject [B]lacks into art history.” Initially, he did this by creating his own versions of classic works. Thus, his George Washington Carver, in satirizing one of the most famous images of Americana, has a Black chef, a barefoot fisherman, a banjo strummer, a moonshiner, and a Black female performing a sex act on the flag bearer at the center of a boat which may be about to spring a leak. The painting was called “the most gleeful and unbridled attack on racist ideology in his oeuvre” but it is also a celebration of various forms of Black working and underclass activity.

In the 1970s Colescott broke free from the de-politicized abstract tradition, the establishment of which is described in my book Cold War Expressionism: Perverting the Politics of Perception. His goal was, as he put it, “to interject [B]lacks into art history.” Initially, he did this by creating his own versions of classic works. Thus, his George Washington Carver, in satirizing one of the most famous images of Americana, has a Black chef, a barefoot fisherman, a banjo strummer, a moonshiner, and a Black female performing a sex act on the flag bearer at the center of a boat which may be about to spring a leak. The painting was called “the most gleeful and unbridled attack on racist ideology in his oeuvre” but it is also a celebration of various forms of Black working and underclass activity.

His Eat Dem Taters, a parody of Van Gogh’s Potato Eaters, is likewise filled with grotesque images of a Black family, seemingly happy with little, a racist stereotype but also as well commemorating Black sharecropper life, finding the humanity behind the caricature, as Van Gogh’s original celebrated the Dutch peasantry with whom he aligned at the beginning of his career.

Instant Chicken! is a gathering of the racist stereotypes behind the Southern kitchen in a culinary scene dominated by Colonel Sanders with Aunt Jemima applauding Sanders and Black cooks framing the composition. The painting reminds us of the Southern plantation paternalism behind the supposedly benevolent figure of “The Colonel.” The image, rather than being superseded, couldn’t be more relevant, as a Christmas ad, with people trapped in their homes as part of the Corona confinement, had a Sanders snowman delivering chicken to a mixed Black and white family and then sacrificing himself as he melted away after securing the delivery.

The word the art world used to describe Colescott’s antics was “appropriation,” which somewhat denies the originality of what he was doing, presenting it as a form of theft with the term itself taking on a kind of discriminatory and derogatory tone. He partially disdained this label and did not want to be known as a creator who “paints art history in blackface.” A far better way of looking at what he accomplished would be to say that what he was doing was expanding the possibilities of Black representation.

His project is renewed today in a variety of places. In the art world, for example in Kara Walker’s recent piece at the Tate London Fons Americanus, a water fountain, recalling that trope in Western sculpture, which instead of nymphs and sea creatures, displays images, using the water motif, of the African, European, American transatlantic slave trade in a piece on display in the heart of London, historical center of that trade. Likewise, Lovecraft Country, the HBO series, in one episode, “appropriates” the Wolfman theme from the segregationist period of Hollywood history where African-Americans were locked out of the horror genre. A Black woman, who is refused a job at a Chicago department store in the 1950s, makes the horror transformation to a white woman who is then offered a job as a manager at the store. Horror transmutes into the horror of racial inequality.

Colescott came to prominence at a time when American consumer goods were circling the globe, defining experience in fashion, leisure and entertainment. The artist’s variegated and complex view of this culture aligns him with earlier observers like Walter Benjamin who, while a collector himself of the detritus of capitalist production, treating its castoffs as signals from far-off lands, also was attuned, as Fredric Jameson says in his book on Benjamin, to the way these products, which define “capitalism’s rituals,” dominate not only our consciousness but also our sense of time. People think of (capitalist) crisis as an event, Jameson explains, but for Benjamin “the catastrophe is that it just goes on like this.”

In 1978’s The Wreckage of the Medusa, a sly borrowing from Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa, a modern-day ocean liner, à la the Titanic, has crashed, and in the sea are the detritus of society, both humans and objects, all cut into their individual parts—used underwear, trash, beer cans, and body parts, all fragmented in the way consumer society fragments experience. One critic wrote that while Colescott “knows that the ship of civilization is sinking,” “he remains on board.” Another way of seeing the gesture, related to the patch over the leaky George Washington Carver boat, is that he is doing his part to ensure a society weighed down with its own consumerist garbage rightfully collapses and sinks.

Two works with the same subtitle, Down in the Dumps, from 1983, provide diametrically opposed views of this culture. The first, So Long Sweetheart, takes up the motif of depression as Colescott himself at far right, his head in his hands in the tortured image of “The Thinker,” is being left by a naked woman wandering off left. What he is left with are all the objects piled up as if at a dump that may have defined their relationship. The Dump is both his depression as well as the collection of objects—bicycles, tires, straw hats, tennis rackets—which are now also defunct.

Down in the Dumps II, titled Christina’s Day Off. In it, a proud Black woman fashions her existence out of a similar pile of objects (hotdogs, cakes, a teapot), but smiles with satisfaction at how she is able to create a persona from these castoffs. Colescott was well aware of the way capitalism discards its useless artifacts be they workers or objects: “Sometimes people, when they get to be about 30 years old, find it’s time for them to be knocked down, just like buildings.”

Another of Colescott’s preoccupations was the often exploitative presentation in the art world of female bodies in general and the Black female body in particular, including an awareness of his own participation in that process. Colescott, with his thorough grounding in art history, was very cognizant of how a concentration on the white female body necessitated a lack of representation of the Black female body. In one work, he has an African woman gazing into a river, à la Narcissus, and seeing her reflection as a blond pin-up queen.

Later, in Les Demoiselles d’Alabama, he presents all the colors of the spectrum of black and Native American women from beige to brown to umbers to dark brown, with various hairstyles and styles of dress, yet all being registered through the knowing gaze of the blond woman sitting comfortably in the corner who addresses the audience directly.

The artist’s own theory of skin color was that there was no pure black or white but rather infinite shades of coloration, with the peoples of the Earth in close proximity to each other. “The closer you are to Africa, the darker the people are in Southern Europe. The closer North Africa is to Europe, the more European people appear.” This blending of races was for him the actual reality, rather than the rigid distinctions codified in apartheid societies.

He was also keen to put official presentations of pulchritude under the spotlight. In 1976’s American Beauty, the colorful blond pageant winner in the foreground with her trophy smiles, but the smile is belied by a background of black and white “movie stills,” a sort of R. Crumb version of a pornographic film showing the sexual abuse the contest winner had to put up with to ensure her victory.

As a Western artist, Colescott also pointed to his own engagement in this process in his version of Susanna and the Elders (1983) which has a Black and white worker gazing at the blond Susanna as she is about to exit the shower. In a window in the upper corner of the work, Colescott himself appears, a Peeping Tom who is part of this leering. His placement in the painting suggests Max Ernst’s surrealist masterpiece The Virgin Spanking the Christ Child, where Ernst appears as one of three “gentlemen” in a peephole watching a highly sexualized spanking of the bare bottom of the child by Mary. Both point to the way art in general and religious art in particular, while claiming to be sanctimonious, often simply legitimates voyeurism.

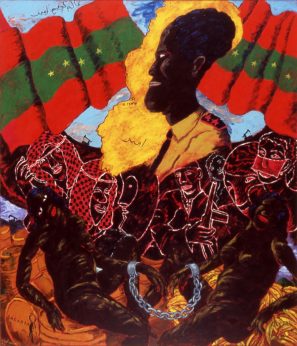

Colescott came to prominence in the moment of the overthrowing of the colonial empires not only in Africa and the Middle East but also in the remnants of the colonial slave system in the U.S. His work has been described as “art that eats away at empire.” His 1992 Arabs: The Emir of Iswid (How Wide the Gulf?) in the wake of the U.S. Desert Storm operation against Iraq, has a Halle Selassie-type figure in the top half of the painting, a memory of the one African ruler who was not conquered as the Europeans carved up Africa, with the title referring to an archeological site which unearthed ancient Egyptian culture. In the middle are Arab nationalists struggling to overthrow the colonial U.S. and European oppressor, and below sit two women chained atop oil cans and a pile of bananas, both items coveted by the continual devastation of Arab lands in the region. Colescott’s critique, of course, is largely ignored in the West, as can be seen in the mid-point “adventure” sequence in Wonder Woman 1984 where the Israeli Gail Gadot as Wonder Woman and the American Chris Pine team up to lay waste to an Egyptian caravan, an almost too blatant enactment of the last half-decade of power relations in the region.

As part of his series titled Knowledge of the Past is the Key to the Future, in Some Afterthoughts on Discovery, Colescott laid bare North American colonialism as on the left a “heroic” Christopher Columbus gazes off into history, oblivious to the lynchings, skeletons, and main figure of a Black worker hobbled by the burden of carrying bales of cotton that make up the center of the work. On the left, a Black woman in a dress with a brilliant floral pattern, seeming to have absorbed this history, strides with pride into her own alternative future.

Finally, in Rejected Idea for a Droste’s Chocolate Advertisement, Colescott mocks the Dutch fairytale Hans Christian Andersen trope as two skaters in typical Dutch dress enjoy the frozen river, with only two elements out of kilter. The woman is Black, surely an indication of the Dutch wealth which came largely from its exploitation of Indonesia and its other overseas colonies, and the man is exposing himself, which suggests, or rather accuses, the Dutch of a history of not only pillage but also of rape in their laying waste to their colonies, referred to also in the title as we recall that Dutch chocolate is not grown but only processed in the Netherlands which profits from its final production while exploiting its growers in the colonies.

Colescott’s career and concerns show him to be an artist who contested the injunction to put aside all political content in art while greatly expanding the range of expression of Black representation. In the end, he helped allow us to reimagine art history and to realign art with its persistent earlier links to an engaged political modernism. In the 1970s and ’80s, artists like Colescott restored both formally and narratively the social content to an art which had seen that content outlawed in the conservative 1950s.

For more on Colescott, listen to Dennis Broe’s talk from the American University at Cairo on this YouTube site.