LYON, France — As times grow more dire, with a major recession looming, war and perhaps nuclear war always on the horizon, and the latest climate catastrophe filling each day’s headlines, audiences are turning to the crime novel with increasing frequency. This popularity was much in evidence recently at what is perhaps the world’s largest crime novel festival, the Quais du Polar in Lyon, which this year boasted 125 authors from 17 countries.

Readers, the majority of them female, according to reader statistics and also according to the evidence in the crowds in Lyon, are showing up either because the “noir” or dark crime novel gives voice to feelings of a challenging and ever deepening crisis or because the “cozy” novel gives them an entertaining respite from the world.

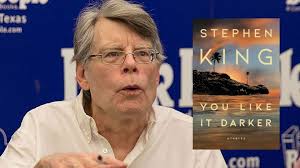

At the same time, the traits of the crime novel are seeping into other genres as well, with the festival’s theme this year being “Borders” or the crossing thereof. Panels featured crime novel authors discussing the environment and climate apocalypse, political fears about the future of democracy leading to novelists’ imagining of a future apocalypse, and horror with a panel tribute to Stephen King whose book of short stories, You Like It Darker, has just been published in France. In Europe the noir novel, embedded in national traditions, also crosses national boundaries, given the popularity of the French roman policier, the country’s dark version of the procedural, Italy’s giallo which, with its yellow, garish covers also encompasses horror, and Germany’s krimi, which also blends historical and philosophical elements with the crime thriller.

At the same time, the traits of the crime novel are seeping into other genres as well, with the festival’s theme this year being “Borders” or the crossing thereof. Panels featured crime novel authors discussing the environment and climate apocalypse, political fears about the future of democracy leading to novelists’ imagining of a future apocalypse, and horror with a panel tribute to Stephen King whose book of short stories, You Like It Darker, has just been published in France. In Europe the noir novel, embedded in national traditions, also crosses national boundaries, given the popularity of the French roman policier, the country’s dark version of the procedural, Italy’s giallo which, with its yellow, garish covers also encompasses horror, and Germany’s krimi, which also blends historical and philosophical elements with the crime thriller.

In France sales of the crime novel have grown by 5 percent in the last two years, and mass popularity has increased, with 75 percent of those sales being in affordable paperbacks. Titles are mandated to be published in a cheaper version according to a law passed in the 1980s by the Socialist Mitterrand government. The most popular sub-genres are cozy crime and the “high-concept” thriller.

However, all is not rosy. Crime novel publishing, as everywhere else, has been hit not necessarily with protectionism but with temerity as publishers are afraid in the current perilous economic climate. David Headley, a British literary agent who represents Scandinavian authors in England, said it was much harder to bring in authors from outside Britain because publishers were “risk averse” in this climate and less likely to commission translations. He pointed to Stieg Larsson’s Millennium as a groundbreaking publication that put what is now called Scandi-noir on the map and opened up the market for authors not only from Larsson’s Sweden but also Denmark, Norway, and now Finland and Iceland. Can Greenland, with dark days looming, be far behind?

Headley acknowledged that France has a vibrant noir tradition but is still awaiting that huge novel that would open up French authors to the English-speaking market.

Two authors whose books badly need to be translated since they offer such a unique take on the genre are the Finn Arttu Tuominen whose novel All The Silences sheds light on Finnish collaboration with the Nazis, and the French crime writer Marin Ledun whose novel Henua equally exposes the barbarity of French colonialism in the Marquesa Islands which 98 percent of the population did not survive.

While what is called “The Winter War” between Finland and Russia at the beginning of World War II is much remarked upon, the aftermath, with the Finns joining Hitler’s Operation Barbarossa and contributing to slaughtering civilians, turns up in the novel 80 years later. On the French side, Ledun, who learned the Marquesa language and now also sports island tattoos, says that in his novel he is trying to dispel the romantic vision, partly propagated by the artist Gauguin, of “docile, sensual” natives who in the present struggle with the long-term effects of not only colonialism but also of French nuclear testing in the archipelago.

The African-American author Attica Locke’s Guide Me Home, the third part of her East Texas trilogy, begins with her Texas Ranger detective resigning from the force during the first Trump era, making his boss think “there was something medically fragile…when really he was just profoundly, unimaginably sad in this new world.” The author herself discussed the fear among African-Americans about this new iteration of a Trump administration while her book remarks upon “the fragility of democracy” in the U.S., a country which dreamed up “an institution of freedom on a foundation built by slaves.”

The Nigerian author Adenle Leye, who now lives in London and whose trilogy highlights Amaka, a female lawyer who protects sex workers against the most outrageous behavior of their ultra-wealthy clients, claimed that Lagos, where the action is set, has the best food on the planet. When Trouble Sleeps begins with a plane crash in a wealthy suburb, the place “where the old money lived.” These are the people, Leye says, who could get a senior officer relocated to the outlying Boko Haram “for not understanding that the job of the police was to protect the rich.” In his heroine Amaka’s dealings with this class she knows those representing this sedimented wealth are nothing but “rich criminals…. These people didn’t need protecting; ordinary Nigerians needed to be protected from them.”

On the same panel, Valerio Varesi put in his own claim for his city of Parma being the food capital of the world with its delicately cured meats and cheeses. Varesi’s Commissaire Soneri loves to walk in the nearby Alps, which Varesi explained were not only a gateway for Italians fleeing fascism during the Mussolini years but also for those wanting a better life and more abundant work in France. Varesi’s inspector out for a vacation in The Dark Valley instead finds himself in the midst of a missing person’s case involving a local magnate who exerts considerable influence in this mountain town where “everything is linked to the pig-farming business and even politicians come out smelling of pork and salami.”

Last but not least, the festival was treated to the jazz improvisations of the American novelist James Ellroy, who “riffed” on several subjects as he discussed his novel about the Kennedys and Marilyn Monroe, The Enchanters. The novel opens with the death of Marilyn, whom Ellroy described as “promiscuous, pretentious and usurious in the extreme,” knowing that this description would enflame his French audience who hold Monroe in high esteem.

“I’m a vulgarian,” he said, trying to further outrage his listeners, and claiming that the only contributions America has made to global culture were the hard-boiled novel, for which he said only he and its original practitioner Dashiell Hammett had any talent, and jazz. Jazz also describes the improvisatory quality of his writing. which in this case begins with the question around Monroe’s death, that is with a traditional melody, but then, as it follows private eye and actual Hollywood figure Freddy Otash who describes himself as “a seasoned peeper/burglar,” explodes into a series of hot vibrations that honk and wheeze in a cacophony of notes cascading against each other.

Rather than truth-telling, which is the ambition of many of these novels, Ellroy simply wants to “make you believe” in these ramblings for the course of the read. The style is as outrageous as the assumptions but, in the end, his is just one voice at Lyon amongst a host of others who want to both entertain and shed light on what is becoming an increasingly darker world, and one in which the noir novel both unveils its deepest secrets and maps the feelings of hope, despair, and anxiety that accompany a rapidly changing, and often, in the noir vision, deteriorating landscape.