Out in Culver City, Calif., there is a cemetery that is, surprisingly, a popular tourist attraction. Perhaps it’s the many well-known celebrities buried there: John Candy, Rita Hayworth, Bing Crosby, and Bela Lugosi; early movie mogul Mack Sennett; director John Ford; and Los Angeles Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley.

But there is only one tombstone in Holy Cross Cemetery engraved with these pure words: “She Loved Baseball.” A fitting tribute to the memory of Effa Manley, the only woman in the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Born March 27, 1897, Effa grew up in Philadelphia but moved to Harlem after graduating high school. She found work in a millinery store in Manhattan making hats and dresses, a job she would never have gotten if the owner thought she was black. Effa was a very light-skinned African-American woman who was able to pass for white on this occasion and others in the future. Her father was a white stock broker and her mother, Bertha Ford Brooks, an African-American seamstress.

Effa was comfortable in her own skin, and never showed any fear of making moves in a white world—no surprise then that she took to modeling in Harlem fashion shows, too.

A huge baseball fan, Effa attended many games at Yankee Stadium, where—as the story goes—she met Abe Manley, another baseball fan, at a 1932 World Series game. Their mutual love of the sport was integral to their initial attraction and to the success of their relationship throughout their marriage.

At home on the field and on the picket line

While Effa had a passion for baseball, she was also an ardent believer in civil rights and social justice. When she found out that white-owned businesses in Harlem wouldn’t hire black people as sales clerks, Effa co-founded the Citizens League for Fair Play with several local pastors. The League tried reasoning with businesses like Blumenstein’s department store, but it got them nowhere. So Effa, never one to back down in the face of adversity, organized a boycott of Blumenstein’s and other businesses and walked a picket line for several weeks that summer, carrying signs that read “We Won’t Shop Where We Can’t Work.”

Eventually, Blumenstein’s and a number of other white merchants relented and black employment in Harlem rose significantly. This wasn’t to be the last time Effa took a stand and struggled for what she believed to be right.

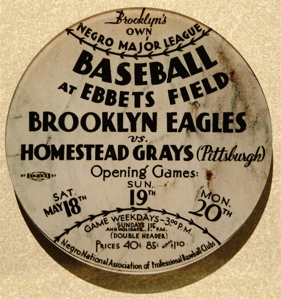

In late 1934, Abe became the owner of a baseball team for the second time (the first folded after only one season): the Brooklyn Eagles of the Negro National League. The League had a spotty history, as there was no central organizing body, no commissioner or even a national office. Players jumped from team to team as owners undercut each other by offering more money to star players. In addition to running their teams, some owners engaged in shady and/or illegal business dealings (one ran the numbers racket for gangster Dutch Schultz), which hurt the credibility of the League. Abe Manley was a good judge of talent, and he put together a team and hired the manager, which took a lot of his time. Someone had to handle the day-to-day responsibilities of the organization—and that’s where Effa came in.

Given the title of “Business Manager,” she was put in charge of all administrative tasks, which came to include Opening Day activities, community relations, special charity events, and—to the chagrin of the other owners—having a significant impact on the future direction of the Negro Leagues as a solidly-run business enterprise.

Abe Manley moved the Eagles from the Brooklyn Dodgers’ Ebbets Field to Ruppert Stadium in Newark, New Jersey where they became the Newark Eagles in 1936. While Abe was busy with the baseball side of the franchise, Effa got busy working in the Newark community to drum up a solid fan base.

Effa knew that while the game itself should be enjoyable, being entertained at the ballpark was just as important to the success of the team as wins and losses. Each Opening Day (the first home game of the season) had the feel of a holiday festival, as local political leaders, well-known athletes, and marching bands were always featured.

Opening Days would feature celebrities, such as world welterweight boxing champion Henry Armstrong and songwriter Andy Razaf of “Ain’t Misbehaving” fame.

But Effa knew that she had more to offer as a businessperson, and so, on February 24, 1940, she attended a meeting of the owners of both the National Negro League and the American Negro League teams.

Effa’s argument that that white promoter Ed Gottlieb’s practice of receiving 10 percent of gross revenue for Negro League games he scheduled at Yankee Stadium was not good for the leagues and that he should not be allowed to do this in the future fell upon deaf ears.

She was voted down in a tension-filled meeting, but Effa did not give up. “We are fighting for something bigger than a little money,” she said. “We are fighting for a race issue. In other words, what we are doing here has become more important than we.”

Her suggestion that a commissioner be hired to oversee both leagues as white professional baseball had done was rejected as well.

While Effa was seen by a number of the owners as a “know-it-all, busy-body woman,” sportswriter Lem Graves Jr. saw her as “an intensely interested, well-informed, capable, efficient and strong-willed woman who runs a man’s business better than most of the men.”

Along with her work as the Eagles business manager, Effa was active in local civil rights causes. In 1941, she offered to sell buttons for the NAACP to help fund transportation for Newark residents to go to Washington, D.C. for a July march to protest racial discrimination in the defense industries. The march was canceled after a June meeting between its sponsors, A. Philip Randolph and Walter White of the NAACP, and President Franklin Roosevelt. At the meeting, FDR signed Executive Order No. 8802 creating the Fair Employment Practices Committee to eliminate race-based hiring practices in the defense industries. Effa also raised money for the Newark Boys’ Club, for those made homeless by the Mississippi River floods of 1937, and for a home for black unwed mothers in Los Angeles. She held an “Anti-Lynching Day” at Ruppert Stadium.

Effa helped fund the Booker T. Washington Community Hospital, which was the only place in New Jersey where blacks could be trained as doctors and nurses, and she served as treasurer for the Newark branch of the NAACP for a number of years.

Being a fierce competitor, Effa hated losing—especially baseball games. Future Hall of Famer Josh Gibson hit a home run to beat the Eagles in their first home game in 1942. After the game, Effa went up to Gibson and said, “Josh, you should be ashamed of yourself, ruining our opener the way that you did. You broke everybody’s heart.” Gibson’s response: “Mrs. Manley, let me tell you this. I’ve been known to break a lot of hearts. I hate to have to do it to you, but that’s my job.”

As the Homestead Grays clobbered the Eagles 21-7 in another unplanned opening loss, Effa could only groan, “It was a terrible game. I never saw so many home runs before in my life. I went home in the third inning and had my first drink of whiskey.”

Her happiest moment at Ruppert Stadium came on September 29, 1946. It was the seventh and final game of the Negro Leagues World Series against the mighty Kansas City Monarchs. With the Eagles leading 3-2 in the top of the ninth, two out and two Monarchs on base, Effa was so nervous she put her face in her hands.

She missed seeing the popup to the first baseman for the final out. Her Newark Eagles were the champions of the Negro Leagues!

Abe and Effa made a good profit as a result of the championship season and rewarded each player with a diamond ring that had “Negro World Champs 1946” printed on it, along with the image of an eagle and the player’s position and uniform number. They also bought a brand new $15,000 air-conditioned bus with “Newark Eagles Baseball Club” and “Negro World Champions” printed on each side. Abe and Effa treated their players well and the players responded with hustle and an exciting and entertaining brand of baseball.

The stealing of Jackie Robinson

While Effa had plenty of beef with men in baseball throughout the years, there was one man she detested above all others: Branch Rickey, Brooklyn Dodgers team president and general manager.

Rickey had made himself highly unpopular with Negro League owners when he said that, “They are not leagues and have no right to expect organized baseball to respect them. They have the semblance of a racket.” He further alienated them when he announced he had a team ready to play in a new black baseball league, the U.S. League, and he would consider absorbing some of the existing teams into his league.

This was, however, just a ruse, as Rickey wanted cover for his scouting of black players for the Dodgers.

When Rickey signed Jackie Robinson to a contract in August 1945, Negro League players rejoiced as many of them hoped to follow Jackie to the major leagues. While Effa was happy that baseball was integrating at last, she was very upset with Rickey for not giving the Monarchs any financial compensation for Jackie. In effect, Rickey had stolen Robinson and there was nothing stopping him from doing it again.

And more baseball theft would come.

Rickey signed catcher Roy Campanella without compensating his team’s owner, and Effa was furious when Rickey signed Eagles’ pitcher Don Newcombe.

“Rickey took Robinson, Newcombe, and Campanella from our Negro baseball and didn’t even say thank you,” she fumed. “We have so many boys who are major league material we may wake up any morning and not have a ballclub, if this keeps on.”

Her words seemed prescient, as more black players were signed by major league teams, diluting the talent in the Negro Leagues. But at least one major league owner thought it was only right to pay for a player’s services: Bill Veeck of the Cleveland Indians.

Effa and Veeck struck a deal that sent Eagles second baseman Larry Doby to Cleveland for $15,000. Effa felt she should have received more, but appreciated that Veeck did not try to steal Doby out from under her, which he could easily have done.

While Robinson’s triumphant 1947 season meant that more black ballplayers might get their chance to play in the majors, this was not good news for the future of the Negro Leagues. After Robinson’s debut, attendance around the Leagues began to drop and the turnout for Eagles’ games fell off significantly. Abe and Effa could see the writing on the wall and knew the Negro Leagues would never recover. A few months after the end of the 1948 season, they sold the Eagles.

Life after the Leagues

After Abe’s death in 1952, Effa devoted much of her time to working for the Newark chapter of the NAACP. In 1958, Effa remarried and moved to Los Angeles, where she lived for the rest of her life. But she wasn’t done with baseball. She co-authored a book on the Negro Leagues titled Negro Baseball…Before Integration, and worked tirelessly to get the Baseball Hall of Fame to recognize the achievements of the great players from the Negro Leagues who never had the opportunity to play in the majors. The Hall did finally admit nine players between 1971 and 1977, but Effa felt that was a slap in the faces of the many other outstanding players from the Negro Leagues.

She was particularly upset that Rube Foster, widely considered to be “the father of Negro League baseball,” was not among the players enshrined in the Hall: “Foster was a great pitcher, great manager, great team operator, great league president, and great promoter. If he’d been white, he would have ranked right up there with Christy Mathewson, John McGraw, and Kenesaw Mountain Landis.”

Effa Manley passed away on March 8, 1981 at the age of 83. Five months later, Andrew “Rube” Foster was inducted into the Hall of Fame.

On February 27, 2006, Effa Manley and sixteen other Negro League players and owners were recognized—finally—as newly admitted members of the Baseball Hall of Fame.

In December 2014, director Penny Marshall announced that she would be directing a biopic about Effa Manley titled Effa. However, three years later, production has yet to start on the film. Effa deserves better than that.