A wave of union organizing drives across the U.S. includes Amazon warehouse workers, coffee baristas, university graduate students and faculty, grocery store workers, nurses, restaurant workers, and food processing workers. Labor militancy has seen a strike wave through the closing months of 2021 and continuing into 2022.

The need to understand the labor movement’s role in the economy has sparked new interest in books like William Z. Foster’s classic American Trade Unionism: Principles, Organization, Strategy, Tactics.

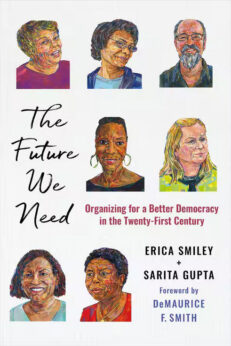

The Future We Need, a new book authored by Erica Smiley and Sarita Gupta, the current and former executive directors of Jobs with Justice, the country’s premier labor-community coalition-building organization, puts into a contemporary frame the enduring issues of worker power and class struggle.

The Future We Need isn’t simply another book about collective bargaining or a manual for winning a better contract. It shows how today’s struggles for working-class power are rooted in the historic battles for civil rights and other proposed radical transformations of U.S. society.

The Future We Need isn’t simply another book about collective bargaining or a manual for winning a better contract. It shows how today’s struggles for working-class power are rooted in the historic battles for civil rights and other proposed radical transformations of U.S. society.

This book is about the use of collective bargaining in all aspects of social existence to win working-class power up to and including the right to govern.

Gupta and Smiley argue, “[T]he power to collectively withhold our participation in an economic relationship can be a powerful way to force concessions from those who seek to get rich on our backs.”

Existing legal frameworks for collective bargaining, as important as they are, were “never meant to address the needs of working people as whole people.” Instead, they were designed “to keep commerce moving, thereby ensuring the success of US capitalism.”

Part of this formal institutional framework excluded many occupations that were predominantly held by Black and Latinx workers, especially women. Created by an alliance of New Deal liberals and Dixiecrats in the 1930s, this structural condition allowed white supremacy to endure in labor organizing, “distorting” how class struggle functioned throughout much of the 20th century.

Racism exposed many Black and brown workers to special oppression and super-exploitation. In the struggle against those conditions, exclusions from the meager protections of labor law made them especially vulnerable to retaliation from the bosses, exploiters, and the state’s repressive apparatus. Existing legal frameworks for unionization—especially through the Taft-Hartley law and various subsequent court rulings—make ignoring the decisive needs of Black and brown workers easy to overlook.

In this regard, the needs of the working class and its development have surpassed the capacity of the political framework to meet our needs, limit our power, and ensure the proper functioning of capitalism.

The struggle against racism in the organized working-class movement depends on multiple factors. The authors underline the critical imperative to expand “our image of US workers themselves” and substantially develop our idea of which issues collective bargaining should address.

Who is ‘the worker?’

If we are only able to imagine white men in our collective social archetype of “the worker,” then we are losing the plot of the class struggle story.

Further, pessimistic arguments that claim that major changes in the global economy have made the labor movement outdated have to be resisted. Financialization, outsourcing, global supply chains, decentralization—whatever symptoms of contemporary capitalism and imperialism that may preoccupy us—have not erased working-class power. Smiley and Gupta show that “power does not necessarily go away. It simply shifts.” It may require new forms of coalition-building, international alliances, the inclusion of workers that are excluded through existing legal frameworks, and abandoning stereotypes about who productive workers are.

More than ever, anti-racist, non-xenophobic, and otherwise unbiased ideas about who should be in the union will be decisive to working-class power.

Further, which activities need to be organized and drawn into collective bargaining—defined by the power to withhold participation in expected economic activities—and to negotiate social needs have to be expanded. Working-class organizers should be prepared to address non-worksite issues like housing, education, healthcare, political power, voting rights, environmental justice, public safety issues, etc. The authors eloquently state, “As the strategies deployed by capital change, the specific mechanisms working people access must also change to apply to all the ways in which humans relate to capital.”

This book shows how to begin to think of conditions in society not simply as issues, but as systemically connected parts of a whole. In order to win any struggle, maintain a structural permanence of such victories, and establish working-class leadership of the whole society, workers have to expand what they understand to be in the domain of struggle. More than ever, understanding capitalism as a whole social formation in class terms is necessary. “The same forces that are weakening worker bargaining power and making work more precarious,” Smiley and Gupta show, “are also undermining public institutions like schools and mass transit, profiting from rising household debt, and shaping policies that are contributing to climate change and environmental injustice.”

This book uses stories from the everyday experiences of communities and workers. It deploys analysis from dozens of years of experience between the two authors in this work. It also draws deeply on a range of labor studies scholarship, working-class economic analysis, and political theory. Accessibly written, the book is organized into three parts: a historical section, a section on existing conditions, and a section on strategies for building labor-community coalitions in effective ways.

Read Foster’s book on trade unionism, but then pick up Smiley and Gupta’s book to spark new ideas and perspectives on what is possible—and needed—now for the working class.