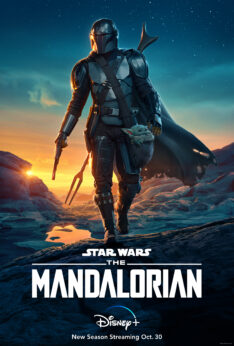

One of the surprise hits of the contemporary streaming era is The Mandalorian, the first original series on Disney+. A surprise not because it was a hit—any Star Wars spinoff is guaranteed to have a wide audience—but because of the magnitude of its popularity and the way it has penetrated the culture. This space Western features a lone gunslinger and bounty hunter who befriends a timeless and seemingly helpless kid, a baby Yoda called The Child, and now named Grogu. The series was twenty times more popular than any other original series on Disney+, the third most popular series (with 1,032 billion minutes viewed) in one of the Nielsen streaming ratings which highly underestimate number of viewers and crucial in Disney+ surpassing 74 million subscribers worldwide in 2020, far beyond its initial goal of 60 million by 2024.

At Christmas, an American workforce seeing its economy evaporate and stuck at home still spent heavily on toys. One of the crown jewels of the toy world was a giggling, babbling Baby Yoda, for $60 no less. In this year when whole film theater chains closed, the animatronic wonder was the only significant seller in film and TV merchandise. This Green Goblin, now a mascot for Disney+, threatened even to replace the angel announcing the birth of Jesus at the top of the Christmas tree.

Part of the furor and adoration is warranted. The first season of The Mandalorian breathed new life into an atrophied franchise. The tale is set after the end of the first Star Wars trilogy where the empire has collapsed but the budding Republic is weak and unable to pull together an unruly universe. Mando, in his quest to preserve and protect this powerful baby, visits a different planet each week, most with broken-down governments and infrastructures. Season one was a fit metaphor for the imminent collapse of the U.S. empire as its currency faltered and economy plummeted in a downturn accelerated but not caused by COVID. The individual planets with their barely surviving frontier systems of government looked a lot like failing American states in the aftermath of the Reagan-Bush-Clinton neoliberal onslaught, finally done in by Trump. The worlds of The Mandalorian also echoed failed states around the world, as parts of the U.S.-dominated global empire collapsed with protests in Lebanon, Chile, Algeria, to say nothing of recent people’s movements in Europe—the Gilets Jaunes (yellow vests) in France, the Indignados in Spain, and the mass movement that led to the momentary success of Syriza in Greece.

Part of the furor and adoration is warranted. The first season of The Mandalorian breathed new life into an atrophied franchise. The tale is set after the end of the first Star Wars trilogy where the empire has collapsed but the budding Republic is weak and unable to pull together an unruly universe. Mando, in his quest to preserve and protect this powerful baby, visits a different planet each week, most with broken-down governments and infrastructures. Season one was a fit metaphor for the imminent collapse of the U.S. empire as its currency faltered and economy plummeted in a downturn accelerated but not caused by COVID. The individual planets with their barely surviving frontier systems of government looked a lot like failing American states in the aftermath of the Reagan-Bush-Clinton neoliberal onslaught, finally done in by Trump. The worlds of The Mandalorian also echoed failed states around the world, as parts of the U.S.-dominated global empire collapsed with protests in Lebanon, Chile, Algeria, to say nothing of recent people’s movements in Europe—the Gilets Jaunes (yellow vests) in France, the Indignados in Spain, and the mass movement that led to the momentary success of Syriza in Greece.

This degradation can be seen also in a comparison of the leading females of the original trilogy and this new iteration. Carrie Fisher’s Princess Leia battled and was a rallying figure around opposition to the fascist Darth Vader and the Death Star. The leading female figure in The Mandalorian was the now-fired Gina Carano’s Cara Dune, a gun-toting warrior on-screen and off-screen a Trump supporter and former wrestler known for her viciousness in the ring. Carano, now one of the world’s most popular celebrities and a tweeter of racist, anti-democratic, and pro-COVID positions, was the Princess Leia of a broken-down generation, buffeted about by the neglect of an ever greedier capitalism and hardened not so much to resist that neglect but to survive it in whatever way possible, not excluding the embrace of fascism.

The trimmings of The Mandalorian, though, couldn’t have been cleverer, with the musical theme a combination of both John Willams’s Star Wars majesty intermingled with the ominously tense strands of Ennio Morricone’s themes for the Sergio Leone-Clint Eastwood spaghetti Westerns. The weekly trip to another planet was borrowed from the original Star Trek as were the end-credit freeze-frames of action in the episode.

Season two began as more of the same, but as the quest to find Baby Yoda’s home took center stage, the show slowly and then more frenetically drew in components and characters from the extended Star Wars world, or as it’s called using the Marvel example, the Star Wars universe. These included the bounty hunter Boba Fett from the original trilogy but also from the second, mostly unsuccessful, prequel trilogy, and Rosario Dawson’s female Jedi Ashoka, a voice-over in the last episode of the most current trilogy and one of the stars of the animated series Star Wars: The Clone Wars, a character fleshed out in that series by Dave Filoni, co-creator of The Mandalorian. The ultimate inclusion, though, was the surprise at the end of the series with the reappearance of the first trilogy’s key character Luke Skywalker played by a reanimated and youthful Mark Hamill, arranged by both the digital reverse aging technique used by Scorsese for DeNiro, Pacino, and Pesci in The Irishman and a mounting of Hamill’s face on a contemporary body.

The move was heralded by Star Wars fans as a crowning touch in the acceptance of the series into the extended universe with its creator George Lucas now being whispered as himself part of season three.

Of course, it was something else too, and that was a gigantic lure for the Disney+ streaming service, which has produced little original content and which has now used this hit as a launching pad for nine new Star Wars series. The company has had to move more actively and rapidly into streaming as other parts of the empire, specifically its theatrical films, amusement parks and cruise ships, falter due to the virus.

Disney is all about synergy, that is, with one part of the company interacting and promoting another. Thus, having bought the Star Wars franchise, not only did the film beget the series but Disney is also borrowing the concept of the “universe” from another company it now owns, Marvel, as well as crossing personnel from the two universes. Thus, the upcoming series The Book of Baba Fett will co-star as the outlaw’s sidekick Fennec Shand Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D.’s Ming-Na Wen. Elsewhere, Marvel guru, studio chief and keeper of the universe flame Kevin Feige is developing a new Star Wars movie which will supposedly extend into infinity this new universe. Each of these series and films of course will also be designed to generate cuddly figurines as both toys and collectibles so that the commercial reach of these shows and films extends beyond the screen.

The carnivore culture

There is something else going on here besides mass merchandising, though. The limiting of creativity even in this overly commercialized product, so that the show in season two begins to fold into itself and collapse into an already established pattern and constellation, is an indication of a culture that is eating itself. More than carnivore, the show is now emblematic of an autophagic, or self-consuming, culture that quickly extinguishes any spark of the new by folding it back into the tried and comfortable and in that way annihilating it.

As such, the journey of The Mandalorian is not so different from that of the country itself. A once powerful manufacturing juggernaut, the U.S. has now been utterly hollowed out so that manufacturing, or making stuff, accounts for only one in 20 businesses and one-ninth of the workforce as opposed to after World War II where one-third of the workforce was employed in factories. The art of producing material goods has been replaced by the symbolic economies of finance, entertainment, and the digital. The only real manufacturing being done is weapons construction, in the sale of which the U.S. leads the world.

Instead, manufacturing has fled to China and other parts of Asia so that by December of last year China, back at nearly full capacity after recovering from the coronavirus, had a record trade surplus of $75 billion. Over $50 billion of that figure consisted of exports to the U.S., where stay-at-home consumers were eagerly buying up Chinese made home fixtures and toys for Christmas, including the aforementioned Hasbro Baby Yoda doll, manufactured in a Chinese factory.

This hollowness or emptiness at the core of the society, reflected in the entertainment complex as lack of innovation so that any spark of creativity must quickly fold back into preestablished patterns, is at play also in the finance industry in the form of stock buybacks. After the 2008 financial collapse and continuing with the COVID aid to American banks, insurance agencies, and investment firms, the financial sector, instead of investing in the society as a whole or in innovating in its firms, bolstered their position by using the money to repurchase shares in their own, often faltering, companies. This outlay resulted in zero gain for the society as a whole but enormous profits for their own shareholders since the stock value was now, artificially, increased. The rationale for propping up this zombie culture was, “We don’t see any better investment than in ourselves,” a phrase which reaffirms their greed and lack of interest in the society as a whole.

This is where much of the money from Trump’s tax cuts for the wealthiest, supposedly designed to “trickle down” to the rest of the society, went, with over $806 billion in buybacks in 2018 after the 2017 tax cut. In that year, only 43 percent of the 500 wealthiest companies spent any money, even a penny, on research and development, while spending $4.3 trillion on propping themselves up in the market and enriching themselves.

When these companies were recently challenged on the market by the Reddit traders, using a failed brick and mortar company GameStop to wage war on the established hedge funds, this popular mass of traders, separate from the established Wall Street cronies, ended their communiqués with The Mandalorian phrase, “This is the way.”

And indeed, it was the way on the series for a season, that is before the show finally folded in on itself and became part of the same carnivore culture so rampant in the industrial and financial worlds. As the stakes increase for the streaming services they move as well to squelch innovation. Witness HBO Max’s return of Sex and the City as well as a redo of Gossip Girl and a Friends reunion special to announce the return of that series to the AT&T fold where it is designed to bolster fading HBO Max subscriptions.

While the right worries about cancel culture—and the left ought to also because the great unwashed neoliberal middle will be coming for progressives next—the bland corporate élite produces a carnivore culture by feasting on what is left of the carcass of a once thriving entertainment and economic complex. In this new chasing after the last vestige of abundance in a fading financial structure the promise of plenitude that begat the streaming era has ceded to the kind of remake and redo policy that has driven the Hollywood film industry. If the monoliths of AT&T/HBO and Disney prevail, this lack of innovation in a culture feeding on itself will become the dominant. With American corporate and conglomerate capital, unfortunately, “This is the way.”