New York City’s Metropolitan Opera, housed at Lincoln Center, ranks among the highest and most sophisticated expressions of artistic culture in the United States. The company shares a global renown with the leading opera houses of Europe.

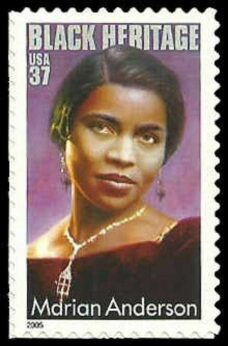

The Met attracts a great deal of attention, not only as a leader in the cultural field but also in terms of its history and evolution as a bellwether of racial consciousness. Music and social historians point to the long-delayed 1955 Met debut of African-American mezzo soprano Marian Anderson (1897-1993), then in her 50s and already past her prime, as Ulrica in Verdi’s The Masked Ball, and to the starring roles of significant numbers of African-American performers in the decades since.

The Met attracts a great deal of attention, not only as a leader in the cultural field but also in terms of its history and evolution as a bellwether of racial consciousness. Music and social historians point to the long-delayed 1955 Met debut of African-American mezzo soprano Marian Anderson (1897-1993), then in her 50s and already past her prime, as Ulrica in Verdi’s The Masked Ball, and to the starring roles of significant numbers of African-American performers in the decades since.

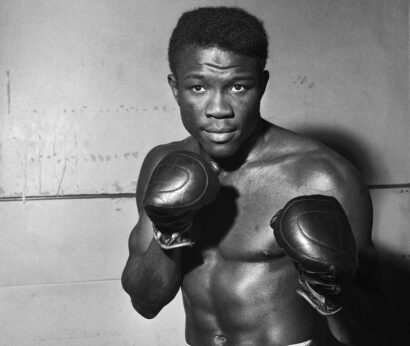

Yet it was not until Terence Blanchard’s opera Fire Shut Up in My Bones, based on the coming-of-age memoir of the African-American New York Times columnist Charles M. Blow, that the Met had ever presented an opera by a Black composer. That opera, opening the 2021-22 opera season with its all-Black cast, rocked audiences with its powerful story, musical interest, and inventive staging. It was so well received that the Met committed to Champion, actually Blanchard’s first opera, with a libretto by Michael Cristofer, a Pulitzer Prize and Tony Award winner for his play The Shadow Box. Champion is based on the true story of boxer Emile Griffith (1938–2013).

Aside from the operas he has composed, a late development in his career, Blanchard continues to enjoy a successful career in jazz as both composer and trumpeter, and he has made his mark in film scoring, providing music for several Spike Lee movies.

The most salient moment of Griffith’s career took place in 1962 when he faced the Cuban-born Benny Paret in the ring. Before and during the match Paret had tried to distract Emile from his game with taunts that he’s a “maricón,” a vulgar term in Spanish for homosexual. In the hyper-masculine world of boxing, especially at that time, there was simply no place for genteel acknowledgment of diversity in sexual orientation. In a supercharged rage against Paret’s words, against oppression, against the thwarting of his own plans for his life, against all the hurts he had suffered as a child, Griffith struck out mercilessly—as he’d been told he needed to—landing 17 hard blows on his cocky Cuban opponent in less than seven seconds, all on live TV. Paret was thrown into a coma from which he never emerged, and within days he was dead.

The opera is set in a series of flashbacks between the Griffith of that time and the older man, now suffering serious boxing-induced dementia, played by different performers. As an old man, Griffith seeks some kind of forgiveness, which he finally receives from Benny Paret’s son.

Griffith’s story is not unknown to the world. A book was written about him, Nine… Ten… And Out!, and there’s a documentary film as well, Ring of Fire: The Emile Griffith Story.

“The thing that really got me about Emile’s story,” Matt Dobkin quotes the composer in “Love and Boxing,” an essay written for The Met, “is the whole idea of accomplishing something major in your life but not being able to share that openly with someone you love. Thinking about the inequities that people experience in the world because of social dogma—really appealed to me as a subject. There’s a moment when he says, ‘I killed a man, and the world forgave me. Yet I loved a man, and the world wants to kill me.’ That, to me, was a very, very, very powerful notion.”

The role of the young Emile Griffith will be assumed by bass-baritone Ryan Speedo Green, also interviewed by Dobkin. “Emile is an amazing character to me because he has so many facets,” says the singer. “He’s not only vivacious and alive, an in-the-moment type of personality, but he also has these deep emotions, not knowing who he is and where his place is in this world.

“I think Emile Griffith would probably be one of the most popular people on the planet if he were young today. He was a person who was not afraid of expressing himself. And that made him awkward and weird to some of the people around him. But he tried to be true to himself. The fact that he was a hat-maker as a teenager, before he ever started boxing, and that a hat-maker could literally become a weapon in the ring is an amazing thing.”

The seasoned bass-baritone Eric Owens, who has sung leading roles in opera houses around the world, returns to The Met as Griffith’s older self. Champion also features soprano Latonia Moore as Emile’s mother (she also played the mother in Fire Shut Up in My Bones), and mezzo-soprano Stephanie Blythe as the owner of a bar Emile frequents and who serves as a friend and counselor.

The director is James Robinson, who also worked on Fire and the acclaimed production of the Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess, with choreography by Camille A. Brown. The Met’s Music Director Yannick Nézet-Séguin conducts, as part of his company’s commitment to continue introducing new works by underrepresented composers on fresh topics that will help to broaden the operatic art form with new audiences and fans.

The Met has scheduled nine performances of Champion, beginning on April 10 and concluding on May 13. It will be live streamed on HD into movie theaters on April 29, and that performance will also be broadcast on May 27 on the Metropolitan Opera International Radio Network.

A quick behind-the-scenes video of a photo shoot can be viewed here. For the full schedule, see here.

The Met has issued a Content Advisory that Champion contains adult themes, sexually explicit language, and physical violence.