CULVER CITY, Calif.—Count on this city’s unique Wende Museum for always thought-provoking historical and cultural programming relating to the Cold War in all its aspects. Its two current exhibitions are “War of Nerves: Psychological Landscapes of the Cold War,” a collaborative initiative of the Wende Museum and Wellcome Collection, and “Red Shoes: Love, Politics, and Dance During the Cold War.” These exhibitions will be on view through January 13, 2019.

Life on earth changed

“War of Nerves” examines the many ways life on earth changed after the detonation of the atomic bomb in 1945. The Soviet Union followed the United States by only four years, testing its first nuclear weapon in 1949. Everywhere in the world, the threat of nuclear war and even annihilation colored people’s perceptions. Personal and national safety, and even an existential future for the planet, were not only no longer guaranteed in life, but became costly, stressful obsessions.

At the same time, perversely, the threat galvanized patriotic sentiment on both sides of the global divide, each side blaming the other for the permanent nuclear state of crisis, each side thinking its own leaders were the guys wearing the white hats. “Being prepared, and taking medical precautions for the aftermath, allowed for a sense of control over the uncontrollable.” Some kids curling themselves under their desks at school as practice for a nuclear attack may have felt their teachers were making them safe, but probably most of them, and certainly their parents, figured out that radiation was not going to just settle like dust on top of those desks and leave untouched the scared children huddling underneath them.

No wonder the 1950s—supposedly the “quiet years” of the Eisenhower administration and the McCarthy political blacklist—also gave birth to the antiwar, antinuclear folk movement. The people on both sides did not want war, yet the impulse toward it seemed unstoppable. Even Eisenhower himself had to belatedly admit it in his farewell address when he referred to the “military-industrial complex.”

The exhibition features a generous collection of graphic materials and physical objects illustrating this terrifying state of mind on both sides of the world. It includes renderings of fallout shelters in both the USSR and China—I don’t know why, but somehow I had thought of those as a peculiarly American phenomenon. It also includes artifacts of resistance against the war mentality.

In addition, sections of the exhibition cover subjects such as mind control, which became a prominent factor in the way Americans understood the Korean War. “Brainwashing, and associated conspiracy theories, became ubiquitous plot devices in popular culture. For the subjects of real-life brainwashing experiments, the effects could be traumatic and far-reaching.”

A small display shows a chess board with the final position of a famous 1978 match. “The 1978 World Chess Championship took place in Baguio City in the Philippines. Players Anatoly Karpov and Viktor Korchnoi were both Russian, but Korchnoi had defected to the West in 1976, and the championship became a Cold War grudge match. Psychology and propaganda eclipsed the chess itself, as Karpov was charged with receiving secret messages via pots of yogurt, and his assistant was accused of telepathic interference with Korchnoi’s gameplay.” The musical Chess, with music by Benny Andersson and Björn Ulvaeus of the pop group ABBA, reflects that era.

The nuclear fallout on children is illustrated by toys and dolls, board games and play weapons. The exhibition draws on the extensive holdings of the Wende in many aspects of popular material culture, including banners, posters, paintings, and fabrics. Even playgrounds were designed as rocket ships and radar defense stations.

Surprisingly, though appropriately, the exhibition includes a gay angle, with a set of four photographic prints by émigré artist Yevgeniy Fiks that riffs off Sen. Joseph McCarthy’s statement that “Homosexuality is Stalin’s atom bomb to destroy America.” (Who knew?) Fiks places “a cut-out image of the first Soviet nuclear-test explosion…at a number of known gay cruising sites…in Washington, D.C. The 1950s was a period of paranoia and persecution of suspected communists and homosexuals working for the U.S. government, and many politicians sought to explicitly link the two. Fiks explores, among other things, the irony that homosexuality was also criminalized in Stalin’s Soviet Union.”

This is a richly rewarding and extremely well conceived show that counts as one of the Wende’s best—in part because of the East-West balance it achieves. It recalls an era of which many younger people have no living memory. Yet the nuclear threat still hangs over humanity. As novelist William Faulkner wrote, “The past is not dead. In fact, it’s not even past.” If young people are not fretting about the bomb any more—although they should, considering the fingers hovering over those red buttons—it’s devastation by global warming for their generation: drought, wildfires, hurricanes, tsunamis, rising oceans, catastrophic weather patterns, earthquakes. As Gilda Radner, another great American thinker, used to say, “It’s always something.”

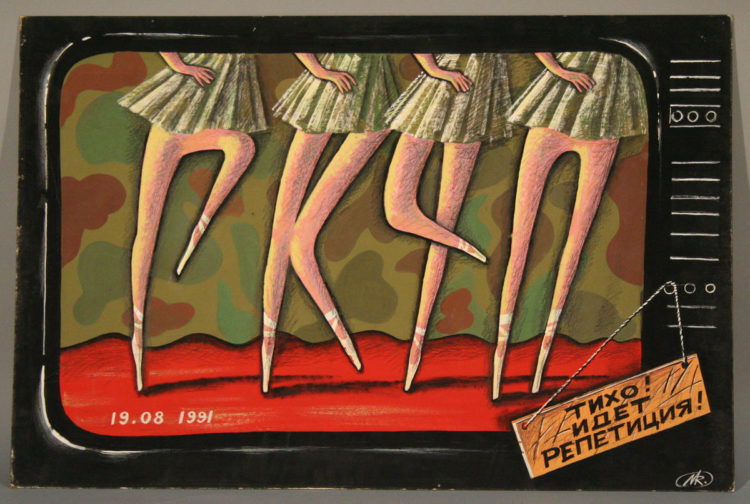

The smaller exhibition “Red Shoes: Love, Politics, and Dance During the Cold War” looks at cultural expression as a weapon in the titanic struggle between two great opposing powers. Now here’s something curious to think about: In the socialist USSR, which for so long rejected jazz and abstract art, the classical 19th-century ballet tradition, considered reactionary in modern dance circles, became the pinnacle of all the arts, almost a national mania and point of civic pride. Russian ballet was admired and envied throughout the world. The many new Soviet-era ballets adapted standard classical technique to socialist themes. The Soviets gave a similar treatment to opera and concert music. Even the country’s famous national folk ensembles “lifted” ethnic dance and music to world-class commercial heights, if perhaps some authenticity was sacrificed.

Meanwhile, the U.S. devoted an infinitesimally small amount proportionally to the arts, compared to other advanced nations. What it chose to send abroad during the Cold War were often the most distinctly “alternative” art forms such as jazz ensembles and Expressionist paintings that were not necessarily the most popularly loved cultural genres at home. The State Department wanted to show how “free” artists were in the United States by comparison to the restrictions placed on Eastern Bloc nations.

“For decades after the Bolshevik revolution, there was virtually no official cultural exchange between the two countries. But during the Cold War, both governments saw value in promoting cultural exchanges and began to structure them.

“Complex negotiations brought tours of ballet companies from both sides, sometimes aided by impresario Sol Hurok. From the Soviet Union came the Bolshoi in 1959, featuring renowned ballerina Galina Ulanova. This was just the first in a long series of U.S. tours for the Bolshoi.

“American Ballet Theatre came to the Soviet Union first, in 1960, headed by legendary dancer Maria Tallchief. They were followed by New York City Ballet in 1962, led by Russian-born choreographer George Balanchine, who was returning to his homeland after an absence of more than 40 years.

“In the U.S., performances by Soviet performing artists sometimes were also the sites of protests by American activists concerned about about the poor treatment of Soviet Jews, and other human rights issues.”

The afternoon I visited these exhibitions (Oct. 7), the Wende sponsored an interview with a renowned concert pianist and piano teacher at UCLA, Inna Faliks, born in Odessa, Ukrainian SSR. She and her family left the Soviet Union in 1989, when she was ten years old. She spoke of her Soviet childhood with some emotional fondness, and also with a degree of remove after almost three decades in the West, and played a few pieces on the piano. She had her early musical training in her homeland, aided by the fact that her mother was an accomplished piano teacher herself.

Just the previous day I had attended the Metropolitan Opera live movie house broadcast of Verdi’s Aida. Soviet-born soprano Anna Netrebko, who received her early musical training in the USSR, sang the title role. In addition, the other two principal singers, her lover Radamès, the Latvian tenor Aleksandrs Antonenko, and her rival Amneris, Georgian mezzo soprano Anita Rachvelishvili, were also Soviet-born and -trained. The USSR may be long gone now, but the devotion it poured into culture and the arts in still on view worldwide.

Upcoming events at the Wende Museum include the following:

A lecture by Karen Petrone on “Gender and War Memory in Putin’s Russia,” Sun., Oct. 21 at 3 pm. How do societies remember war? And how do collective memories affect present-day politics and life? From soldierly masculinity to the role of women in raising the next generation of soldiers, historian Karen Petrone—author of Life Has Become More Joyous, Comrades and The Great War in Russian Memory—will explore how Russian memories of World Wars I and II are inextricably linked to how Putin’s Russia defines citizenship, promotes nationalism, legitimates militarism, and upholds gender hierarchies. Free, but RSVP required.

A lecture by Karen Petrone on “Gender and War Memory in Putin’s Russia,” Sun., Oct. 21 at 3 pm. How do societies remember war? And how do collective memories affect present-day politics and life? From soldierly masculinity to the role of women in raising the next generation of soldiers, historian Karen Petrone—author of Life Has Become More Joyous, Comrades and The Great War in Russian Memory—will explore how Russian memories of World Wars I and II are inextricably linked to how Putin’s Russia defines citizenship, promotes nationalism, legitimates militarism, and upholds gender hierarchies. Free, but RSVP required.

A Culver City Happy Hour with Curator’s Talk on “Culture and Power,” Fri., Oct. 26, drinks in the garden from 6-8 pm, and at 7 pm, the curator’s talk. Most societies distinguish between our material existence and the spiritual forces that shape our lives. In modern Europe, this idea took the form of a struggle between culture and power. Chief Curator and Director of Programming Joes Segal will discuss the ideas of various modern philosophers, including Kant, Hegel, Marx, Nietzsche, Foucault, Said and Huntington, in an attempt to illuminate how will they might or might not shed light on our current state of affairs. Free but RSVP required.

The Jewish Women’s Theatre presents “Past & Present: Russian Jewish American Stories” on Sun., Nov. 11. At 5 pm come for a private museum viewing and reception, and a 6 pm performance followed by Q&A. The Jewish Women’s Theatre develops and adapts stories, plays and songs of Russian-speaking Jews in an evening of entertainment that will offer a deeper sense of human connection through tales of Russian Jewish life in the former Soviet Union and in America today. Tickets are required and can be purchased by clicking here.

On the Wende Museum website you will also find information about their upcoming musical offerings.

Admission to all exhibitions and most public programs is free and open to the public. Regular visitor hours are Fri., 10 am–9 pm, and Sat. and Sun., 10 am–5 pm. The museum is located at 10808 Culver Blvd., Culver City, CA 90230. The main telephone number is (310) 216-1600.

Sources: The opulent catalogues for the two exhibitions.