Within the last twenty years, many thousands of women worldwide have begun to celebrate International Women’s Day (IWD). However, the way in which the day is marked often bears little resemblance to the original IWD purpose and origins.

This is a great misfortune, especially in the current climate in which there is an attack on the fundamental principle of women’s rights.

IWD was founded at the beginning of the last century to both highlight and celebrate the struggle of working women against their oppression and double exploitation.

Today, this fight has not been won—their struggle is still our struggle. Thus, it is timely to remind women and men in the labor movement and elsewhere of the inspirational socialist origins of IWD in the hope that it will ignite again a progressive socialist feminist women’s movement rooted in an understanding of the class basis of women’s inequality. We can learn from our history, but first we must rediscover it.

The motivation for IWD came from two sources—the struggle of working-class women to form trade unions and the fight for women’s right to vote.

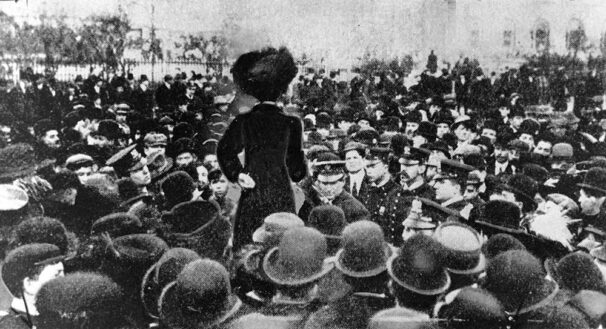

These two issues united European women with their sisters in the U.S. In 1908, hundreds of women workers in the New York needle trades demonstrated in Rutgers Square on Manhattan’s Lower East Side to form their own union and to demand the right to vote.

This historic demonstration took place on March 8. It led, in the following year to the “uprising” of 30,000 women shirtwaist makers, which resulted in the first permanent trade unions for women workers in the U.S.

Meanwhile, news of the heroic fight of U.S. women workers reached Europe—in particular, it inspired European socialist women who had established, on the initiative of the German socialist feminist Clara Zetkin (1857-1933), the International Socialist Women’s Conference.

This latter body met for the first time in 1907 in Stuttgart alongside one of the periodic conferences of the Second International (1889-1914).

Three years later in 1910, Zetkin proposed the following motion at the Copenhagen Conference of the Second International: “The Socialist women of all countries will hold each year a Women’s Day, whose foremost purpose it must be to aid the attainment of women’s suffrage. This demand must be handled in conjunction with the entire women’s question according to Socialist precepts. The Women’s Day must have an international character and is to be prepared carefully.”

The motion was carried. March 8 was favored, although at this stage no formal date was set. Nonetheless, IWD was marked by rallies and demonstrations in the U.S. and many European countries in the years leading to World War I, albeit on different days each year (e.g. March 18 in 1911 in Austria-Hungary, Germany, Denmark, and Switzerland and the last Sunday in February in the U.S.). It was not marked or even noticed in Britain until much later.

In 1917 in Russia, International Women’s Day acquired great significance—it was the flashpoint for the Russian Revolution. On March 8, (Western calendar) female workers in Petrograd held a mass strike and demonstration demanding peace and bread. The strike movement spread from factory to factory and effectively became an insurrection.

The Bolshevik paper Pravda reported that the action of women led to revolution, resulting in the downfall of the tsar, a precursor to the Bolshevik revolution. “The first day of the revolution was Women’s Day… the women… decided the destiny of the troops; they went to the barracks, spoke to the soldiers, and the latter joined the revolution… Women, we salute you.”

In 1922, in honor of the women’s role on IWD in 1917, Lenin declared that March 8 should be designated officially as Women’s Day.

Much later, it was a national holiday in the Soviet Union and most of the former socialist countries. The Cold War may explain why it was that a public holiday celebrated by communists was largely ignored in capitalist countries, despite the fact that in 1975 (International Women’s Year), the United Nations belatedly recognized March 8 as International Women’s Day.

Today, we acknowledge that IWD gives us an opportunity to draw attention to our own struggles for women’s rights, to link this with women’s struggles worldwide, and to demonstrate international sisterly solidarity with working women everywhere.

This is now more urgent than ever. We are witnessing the persistence of the gender pay gap, the increasing feminization of poverty, the closure of women’s safe spaces, and an insidious attack on the very notion of women’s rights in favor of the ideology of identity politics.

This is why all those who are celebrating IWD should not forget its socialist feminist origins. We should use March 8 to pledge to redouble our efforts to protect and extend women’s rights “for the many not the few.”

The price of women’s equality demands eternal vigilance.

Morning Star