Although reluctant to say it, a recent IMF report on the state of U.S. economy makes clear that U.S. policy makers have failed to protect majority living conditions.

When a country joins the IMF, it agrees to have its economic and financial policies evaluated, in most cases annually, by an IMF team of economists. As the IMF explains:

“The IMF’s regular monitoring of economies and associated provision of policy advice is intended to identify weaknesses that are causing or could lead to financial or economic instability… The consultations are known as ‘Article IV consultations’ because they are required by Article IV of the IMF’s Articles of Agreement.”

The IMF recently concluded and published a summary of its Article IV consultations with the United States. While the IMF generally pulls no punches in criticizing the policies of most member governments if it determines that they threaten to slow capitalist globalization dynamics, it tends to tap dance around disagreements when it comes to the policies of its more powerful member countries, especially the United States. As economic historian Adam Tooze points out in his commentary on the IMF statement:

“With respect to the U.S., the stakes are particularly high. The U.S. has the largest vote on the IMF’s board and Congress controls the largest part of the IMF’s budget.”

“The U.S. economic model is not working as well as it could in generating broadly shared income growth.” – IMF

Not surprisingly, then, the IMF went the extra mile in finding nice ways of talking about the state of the U.S. economy and even more importantly the wisdom of Trump administration policies. Even so, U.S. economic challenges could not be completely hidden. For example, after noting that the “The U.S. economy is in its third longest expansion since 1850,” the IMF goes on to comment:

“However, the outlook is clouded by important medium-term imbalances. The U.S. economic model is not working as well as it could in generating broadly shared income growth. It is burdened by a rising public debt. The U.S. dollar is moderately overvalued (by around 10-20 percent). The external position is moderately weaker than implied by medium term fundamentals and desirable policies. The current account deficit is expected to be around 3 percent of GDP over the medium-term and the net international investment position has deteriorated markedly in the past several years. Most critically, relative to historical performance, post-crisis growth has been too low and too unequal.

“To address these shortcomings, the administration intends a wide-ranging overhaul of policies, although a fully articulated policy plan has yet to emerge. The administration’s budget proposes to reduce the fiscal deficit and debt, to reprioritize public spending, and to revamp the tax system. However, during the Article IV consultation it became evident that many details about these plans are still undecided. Given these policy uncertainties, the IMF’s macroeconomic forecast uses a baseline assumption of unchanged policies. Specifically, it neither builds in the effect of tax reform nor the expenditure reductions proposed in the administration’s budget. Under this forecast, growth is expected to rise modestly above 2 percent this year and next, driven by continued solid consumption growth and a cyclical rebound in private investment. Growth is forecast to subsequently converge to the underlying potential growth rate of 1.8 percent.”

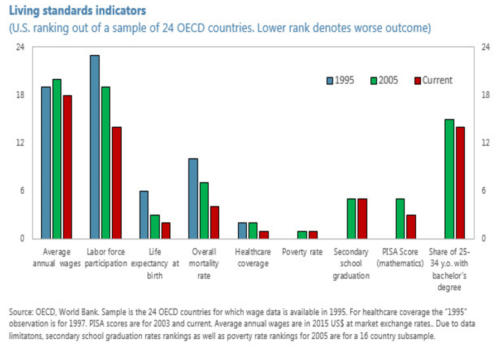

However, IMF concerns over an uncertain U.S. economic outlook and an unclear Trump administration policy plan pale in importance compared to the decline in U.S. living standards illustrated in the following chart that was also in the report.

In broad brush, the U.S.’ ranking on most of the selected living standards indicators has declined, which means that the U.S. economy is losing ground relative to the other OECD countries in the sample. But what really cries out for notice is how low the U.S. is on such key indicators as: life expectancy at birth, overall mortality rate, health coverage, poverty rate, and secondary school graduation. On these indicators, the U.S. is approaching the bottom of the group of 24.

And of course, Trump administration policies, which aim to reduce spending on Medicare and Medicaid, gut worker-protecting health and safety and labor laws, slash taxes on corporations and the wealthy, and weaken unions will only intensify downward trends.

The IMF could easily have pointed out that, because of competitiveness pressures, U.S. policies harm the well-being of workers in other countries as well as in the U.S., and pressed the U.S. government to reverse course. But majority living standards are not the most important thing to the IMF or the U.S. government, and that is not how consultations work.

If we want improved living conditions, we are going to have to fight for them. Perhaps greater awareness of just how bad things are in the United States will help speed the effort.

This article originally appeared at Reports from the Economic Front.