This article is part of the People’s World 100th Anniversary Series.

On March 25, 1931, nine Black youths were arrested in Scottsboro, Ala., falsely accused of raping two white women. The nine, who became known as the “Scottsboro Boys,” at the time, faced certain death in the racist courts of Jim Crow Alabama.

The Communist Party USA and the International Labor Defense came to their defense, initiating a worldwide movement to save their lives and overturn the white supremacist “justice” system in the U.S. South. Other than the African-American press, the Daily Worker newspaper, predecessor of People’s World, was the only national media outlet devoting it full attention to covering the Scottsboro case and the global movement to save the Nine.

In the article below, originally printed in 1989, historian Arthur Zipser recalls the very first issue of the Daily Worker that he ever bought in 1933. It focused almost exclusively on the Scottsboro case. In his article, Zipser recounts the details of the Scottsboro struggle and its importance in the fight for legal justice and Black liberation.

‘They shall not die’

By Arthur Zipser

People’s Daily World, Feb. 15, 1989

I remember the occasion when I first bought a copy of the Daily Worker, an honored antecedent of the People’s World. It was on the boardwalk at Brighton Beach on a bright, sunny, quiet day in early summer 1933. It was sold to me by an earnest middle-aged, needle trades worker.

It was a special issue filled with the shocking facts about the Scottsboro Case, almost to the exclusion of any other matter. The case had started on March 25, 1931, when the nine African-Americans, the “Scottsboro Boys,” as they were soon called, had been rounded up on a freight train at Paint Rock, Alabama. They were falsely charged with raping two young white women whom the police had pulled from another car on the same train.

I was not altogether uninformed about the facts of the case. Friends had given me pamphlets to read. There was one by Joseph North, published by the International Labor Defense. By March 31, a special grand jury had indicted all nine for rape. By April 9, all except 14-year-old Roy Wright had been convicted and sentenced to die in the electric chair on July 10, 1931.

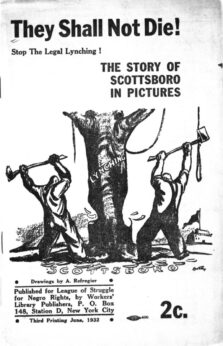

The ILD had intervened immediately after the convictions and had been chosen to handle the further legal options to save the defendants’ lives. I also knew from a 1932 pamphlet (prophetically titled “They Shall Not Die!”) that I was not the only one who had heard about the Scottsboro outrage.

Hundreds of thousands in the United States and foreign lands had moved into the protest movement to save the Scottsboro youths. Scores of prominent people added their voices to the protests: Albert Einstein, Theodore Dreiser, Langston Hughes, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Lincoln Steffens, Maxim Gorky, Mary Heaton Vorse, Henry Barbusse, Michael Gold, and many others were among them.

Vigorous legal action by the ILD, backed by a worldwide protest movement initiated by the Communist Party USA, won skirmishes that kept the defendants alive and scored large and small victories. On March 23, 1932, the Alabama Supreme Court reversed the convictions of Eugene Williams and ordered a hearing in Juvenile Court. Williams was 13 years old. A mistrial was declared in the case of 14-year-old Toy Wright. But both remained in prison.

In early 1933, Ruby Bates, one of the two women who had charged the nine with rape, came over to the side of the defense and admitted that her charge and that of her companion, Victoria Price, had been a lie—they had not even seen the Black youths while on the train. This should have been enough to spring the prison gates for the accused—but not in Alabama. Haywood Patterson was re-tried separately, twice, and sentenced to death a second time and a third. Clarence Norris, age 19, was tried a second time and again sentenced to death.

The ILD continued the mass and legal defense of the jailed youths until 1935 when a Scottsboro Defense Committee was formed comprising the ILD, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the American Civil Liberties Union, the Methodist Federation for Social Service, the League for Industrial Democracy, and the Church League for Industrial Democracy. In the years that followed, the Scottsboro Defense Committee handled the legal side of the case; the ILD continued its worldwide campaign for the Scottsboro youths’ freedom.

In 1937, in what appeared to be the first part of an agreement to free all the defendants, freedom was granted to Roy Wright, Olen Montgomery, Eugene Williams, and Willie Robertson. The others remained in prison when Gov. Bibb Graves reneged on a promise to pardon them. Over the next 13 years, one slowly after another, the Scottsboro men, all in their 30s, were released (or in a couple of instances made their escape). The last to be released was Andrew Wright, who went into jail, at age 18, in March 1931 and was finally freed on June 8, 1950.

When Clarence Norris died this year [1989] on January 23, he was indeed the “last of the Scottsboro Boys.” He was the only one who lived a fairly full measure of years (76) and achieved a normal life. Even in 1976, when Norris was pardoned by Gov. George Wallace (who declared all the Scottsboro Nine innocent), he was already “the last.” All the others, their bodies and spirits undermined by jail and other cruelty, had met early deaths by illness or violence.

Even earlier deaths had been planned by the Alabama courts, but the intervention of the Communist Party, the ILD, and the Daily Worker stayed the executioner’s hand until a mighty united front slowly gained freedom for them all. As by-products of this struggle, the Supreme Court ruled that indigent defendants had a right to counsel in criminal cases, and it also outlawed the systematic exclusion of African Americans from Southern juries.

William L. Patterson of the ILD, who was in the Scottsboro struggle almost from its inception, had this to say (Daily World, Feb. 11, 1975):

“The Scottsboro case is a monumental event in the centuries-old liberation battles of Black Americans. It made history…. the Scottsboro case gave proof that the fight against racist savagery was not the task of Blacks alone.”

We hope you appreciated this article. At People’s World, we believe news and information should be free and accessible to all, but we need your help. Our journalism is free of corporate influence and paywalls because we are totally reader-supported. Only you, our readers and supporters, make this possible. If you enjoy reading People’s World and the stories we bring you, please support our work by donating or becoming a monthly sustainer today. Thank you!

Comments