December 6, 2017, marks the one hundredth anniversary of Finland’s declaration of independence. It is a national public holiday and flag day, celebrating the Finnish nation’s break from Russia.

From the late 13th century, Finland gradually became an integral part of Sweden owing to Swedish part-colonization of coastal Finland, a legacy reflected in the continuing presence of the Swedish language and its official status. Those centuries were the height of Swedish regional power, which extended throughout the Baltic area, touching Germany and Poland.

Nevertheless, Finland always had a distinct national character: Almost 9 out of 10 people in Finland are ethnic Finns who speak Finnish, a Uralic language unrelated to the Germanic Scandinavian languages (Hungarian and Estonian are the two other languages in this group spoken by large numbers of people).

Once Swedish power had waned, starting in 1809 and up to independence, Finland formed an autonomous grand duchy in the Russian Empire. During that century Finns laid the societal and administrative groundwork for eventual independence. In 1906, for example, Finland became the first European state to grant all adult citizens the right to vote, and the first in the world to give all adult citizens the right to run for public office. However, the relationship between the grand duchy and the Russian Empire soured when Russia made moves to restrict Finnish autonomy. Universal suffrage was, in practice, virtually meaningless, since the tsar did not have to approve any of the laws adopted by the Finnish parliament. Desire for independence gained ground, first among radical liberals and socialists.

If imperial Russia was an infamous “prisonhouse of nations” extending from Poland in the west to Siberia in the far east, Finland could be considered one of those captive nations.

Finnish independence in 1917 is directly connected to the Russian Revolution.

After the 1917 February Revolution, which toppled the monarchy, the position of Finland as part of the Russian Empire was questioned, mainly by social democrats. Since the head of state was the tsar of Russia, it was not clear who the chief executive of Finland was now. The Parliament, controlled by social democrats, passed the Power Act to give the highest authority to the Parliament, but this was rejected by Alexander Kerensky’s Russian Provisional Government, which decided to dissolve the Parliament.

New elections were conducted, in which right-wing parties won a slim majority. Some social democrats refused to accept the result, claiming that the dissolution of the Parliament—and thus the ensuing elections—was extralegal. The two nearly equally powerful political blocs, the right-wing parties and the social democratic party, were highly antagonized.

On November 15, within a month of assuming power, the Bolsheviks declared a general right of national self-determination, including the right of complete secession, “for the Peoples of Russia.” On the same day the Finnish Parliament issued a declaration by which it assumed, pro tempore, all powers of sovereignty in Finland. Russia’s Baltic provinces of Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania also declared their independence from Russia during the same period, with approval from Lenin’s revolutionary government.

The thrust for Finland’s independence started after the revolution in Russia provided the opportunity to withdraw from Russian rule. After several disagreements between the non-socialists and the social-democrats over who should have the power in Finland, on December 4, 1917, the Senate of Finland finally made a Declaration of Independence which was adopted by the Finnish parliament two days later.

The Finnish Declaration of Independence states: “The people of Finland feel deeply that they cannot fulfill their national duty and their universal human obligations without a complete sovereignty. The century-old desire for freedom awaits fulfillment now; The People of Finland has to step forward as an independent nation among the other nations in the world.”

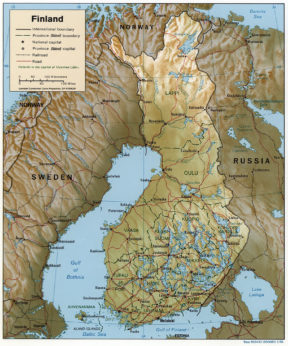

The new country overcame a tumultuous political period following their declaration of independence. In just one year there was civil war that killed 36,600 Finnish people, a staggering number out of the 3.1 million population at the time. The Bolshevik-leaning Red Guard, supported by the new Soviet Russia, fought the White Guard, supported by the German Empire. Finland briefly became a monarchy for a couple of months, then, after their new German prince was defeated in World War I, it became a presidential republic with a central government based in the capital city of Helsinki. Kaarlo Juho Ståhlberg was elected as its first president in 1919. The Finnish–Russian border was determined by the Treaty of Tartu in 1920. The deep social and political enmity sown between the Reds and Whites would last up until World War II and beyond.

Because of its geographical position and its internal political history with sharp opposing forces, Finland struggled to maintain good relations with the two major nearby powers, the USSR and Germany. In World War II Finland became a battleground between these two powerhouse nations. The Finno-Soviet Treaty of 1948 gave the Soviet Union some leverage in Finnish domestic politics during the Cold War era. Finland joined the United Nations in 1955 and established an official policy of neutrality.

Finland was a relative latecomer to industrialization, remaining largely agrarian until the 1950s. After World War II, Finland started developing an advanced economy while building an extensive welfare state based on the Nordic model, resulting in widespread prosperity and one of the highest per capita incomes in the world. Finland is a top performer in numerous metrics of national performance, including education, economic competitiveness, civil liberties, quality of life, and human development. In 2015, Finland was ranked first in the World Human Capital and the Press Freedom Index, as the most stable country in the world, and second in the Global Gender Gap Report.

Finland’s population today is 5.5 million, the majority concentrated in the southern region. It is the eighth largest country in Europe and the most sparsely populated country in the European Union. The Sami people are an indigenous Finno-Ugric people numbering under 100,000 with recognized national rights inhabiting the Arctic area of Sápmi, which encompasses parts of Finland, Sweden, Norway and Russia.

Check out the website here to learn about how Finns will be celebrating this year.

Sources: Finnish historical sites and Wikipedia.