Fifty years ago, after office hours on September 24, 1968, a group of 14 men in Milwaukee entered the Brumder Building at 135 W. Wells St., armed with burlap bags. The building housed nine different draft boards in the offices of the Selective Service Administration. The men gathered up files on draft registrants with 1A classifications—meaning they would be among the next class of inductees to be drafted into the war in Vietnam—and stuffed them into the bags.

The 14 proceeded down to the street below, where in a square dedicated to the memories of WWII dead, they poured homemade napalm over the bags and lit them on fire. They destroyed the draft files on some 10,000 young men, all of whom might otherwise have been swept into the maw of death and injury in an imperialist war halfway around the globe.

At the time, PW readers will recall, a young Donald J. Trump in Queens, N.Y., received a series of deferments from military service, four for being in school and the conclusive one for his troublesome “bone spurs.”

The group included radical Catholics and others motivated by the need to bear witness and take direct action, among them five Roman Catholic priests and a minister. As the draft files burned, the Milwaukee 14 handed out to reporters, whom they had alerted to a “headline” action, a 1500-word press release detailing their reasons for taking this dramatic move. “We who burn these records of our society’s war machine,” the statement read, “are participants in a movement of resistance to slavery, a struggle that remains as unresolved in America as in most of the world.” The activists prayed and sang, and read passages from the gospels. When police arrived they gave themselves up for arrest. They were inspired by a similar action in Catonsville, Md., a few months before, on May 17, 1968.

Bob Graf, one of the defendants in the ensuing trial, recalled years later that as the fire consumed the records, he felt as though he had just rescued someone from drowning.

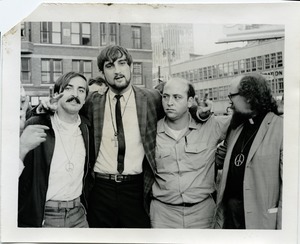

The 14 men also included Don Cotton, Michael Cullen, Robert Cunnane, James Forest, Jerry Gardner, Jon Higgenbotham, James Harney, Alfred Janicke, Doug Marvy, Fred Ogile, Anthony Mullaney, Basil O’ Leary and Larry Rosebaugh.

The charges were burglary, theft and arson to property. Anti-war activists in the community and on local campuses leapt to their defense with gratitude. At a support rally the following day, civil rights leader Father James Groppi said, “I think we had 14 saints out there yesterday who performed a tremendous act of courage.”

To set the event in context, the Democratic Party had just nominated Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey as their presidential candidate, after a disastrous Chicago nominating convention. Humphrey had been a loyal supporter of the war that President Lyndon B. Johnson escalated step by step throughout the mid-1960s, incurring the anger of peace-minded people worldwide. Even against a Republican opponent such as Richard M. Nixon, who promised he had a plan to end the war, Humphrey had lost favor among large swaths of American voters.

At the trial months later, with Nixon now in the White House, the defendants served as their own lawyers, calling expert witnesses to testify about the immoral, illegal war in progress. During the trial, even members of the prosecution team admitted that they opposed the war, but had to enforce the law against the 12’s crimes (two of the Milwaukee 14 had separated themselves from the group for individual trial).

Defending themselves, the 12 took liberties in the courtroom that formal legal representation would not have allowed. They spoke out frequently, mocking the “justice” of disallowing pertinent testimony on the war. Most of the prosecution’s objections to the relevance of such evidence about the mass killings in Vietnam, and the senseless deaths of thousands of young Americans, were upheld. If they had been represented collectively by an attorney, the attorney would have made an opening and a closing statement, but as individuals each one got to make his own set of statements to the jury. The sense of earnest moral duty that the activists conveyed in their eloquent personal faith-based defense registered powerfully with the jury and with those attending the trial. In the end it was transparently not the Milwaukee 14 on trial but America itself.

Journalist Francine du Plessix Gray attended the trial and wrote about it extensively in The New York Review Books. She brought attention to the defendants’ innovative defense strategies: “Early in the trial the defendants moved that the charges of arson and theft against them must be dropped, arguing that 1) market value, not replacement value as the State defined it, determined the value of stolen property and that 2) the State had failed to prove that the market value of the draft records was beyond one hundred dollars, the sum which distinguishes felony from misdemeanor.”

They also invoked “defensive privilege,” the legal principle “which states that actions ordinarily punishable under the criminal code may be considered privileged, i.e., non-criminal, if the action is taken with the ‘reasonable belief’ that it may prevent bodily harm to another party. Claiming ‘privileged’ action, the defendants argued that the events of September 24th were ‘efforts to forestall injury to third persons, third persons being drafted into a war of doubtful legality.’”

Historian Howard Zinn was among those witnesses the Milwaukee 14 called upon. “The tradition of civil disobedience goes as far back as Thomas Jefferson and it comes right up to today,” Zinn testified. “People distinguished in the field of law and philosophy recognize that there’s a vast difference between a person who commits an ordinary crime and a person who commits an act which technically is a crime, but which in essence is a social act designed to make a statement.”

Another witness was John Fried, whom du Plessix Gray describes as “an imposing, silver-haired Viennese-born scholar, [who] had been chief consultant to the American judges at the Nuremberg trials, United Nations Adviser on International Law to the government of Nepal, and adviser on international law at the Pentagon.” “The International Tribunal at Nuremberg, at which the United States was represented,” Fried said on the witness stand, “stated that it is the moral choice of the individual if he feels that for him obedience to the higher order—to the world order—is more important,…then he has to take the moral choice and do the things which he considers morally proper. That is the great ethical and moral method of Nuremberg.”

In May 1969, the jury found all 12 guilty of all charges. The other two were also found guilty. According to Chris Foran, “A month later, a separate federal case against 12 of the men was thrown out when U.S. District Judge Myron Gordon concluded that the extensive media coverage made finding a truly impartial jury impossible.”

Sentenced to two years in prison, the 14 all received early paroles, serving an average of 13 months. Soon after the original event, other similar attacks on draft board records took place in Pasadena, Calif., Silver Spring, Md., and Chicago.

The consensus on the war was fast breaking down and tearing the country apart. Yet the Nixon administration doggedly pursued it, in 1970 expanding it to Cambodia and Laos, which produced the most militant response ever during the anti-war period on the part of students and other activists. The war was unwinnable. The U.S. “Vietnamesed” the war in 1973, but the corrupt South Vietnam government had no legitimate claim on the loyalty of the people. The war ended just in time for May Day 1975 with the entry of National Liberation forces into Saigon, now renamed Ho Chi Minh City.

Sources: Chris Foran,“Our Back Pages: When the Milwaukee 14 made a fiery statement,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, Sept. 20, 2016; Francine du Plessix Gray,“The Ultra-Resistance: on the trial of the Milwaukee 14,” New York Review of Books, September 25, 1969. This site contains additional information about the Milwaukee 14, including news footage of the actual burning and a link to a 10-minute documentary about the incident.