Though often ignored, communities know best what ails them. I am reminded of this often because I hear it in my classroom. I heard it before the COVID-19 pandemic, and I hear it louder now as the pandemic rages on.

At the end of last term, amidst the surge in cases after Thanksgiving, I asked students in my introductory-level public health course to complete a photo essay about the pandemic and what changes they propose to build healthier communities. My students, who represent the tremendous economic, social, cultural, and geographic diversity of New York City and Long Island, are adept at identifying the determinants of health because they breathe, see, and live them. Like many in the NYC metropolitan area—and across the United States—several of my students contracted COVID-19, and many lost loved ones because of the virus.

The COVID-19 pandemic is the latest reminder of the uneven impact of systemic economic and social inequities on health and well-being. Working-class, Black, and Latinx communities suffer from disproportionately higher rates of COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and death compared to wealthier, white, and Asian communities. The same is true for chronic diseases like diabetes and heart disease. Poverty, access to quality health care, and racism are among the major contributing factors.

In New York, Gov. Cuomo often speaks of building back better, the same slogan adopted by the Biden presidential campaign last year. But who decides how we will achieve this? Public health and health care professionals, city planners, elected officials, educators, and local business owners, among others, should and likely will weigh in. Crucially, the voices and perspectives of community members, particularly those hardest hit by the pandemic, must be heard, too.

For the photo essay project, my students photographed a wide array of economic, social, and environmental factors that have contributed to the COVID-19 pandemic. Not surprisingly, myriad common themes emerged, regardless of whether the student lived in Harlem or Brooklyn, the North Shore or the South Shore of Long Island.

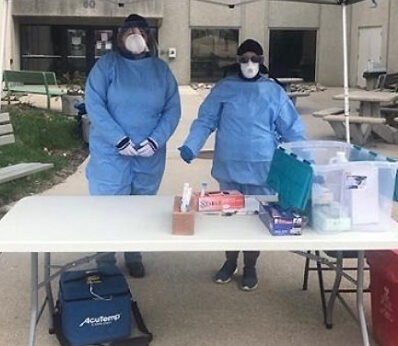

On one hand, my students’ photos demonstrate that there is much to celebrate in their communities. They remarked that mobile COVID-19 testing sites are available in most—albeit not all—communities. Many credited frontline and essential workers for their dedication. Others recognized local, county, and state officials for enacting helpful guidance and for providing personal protective equipment to vulnerable populations. And several students included photos depicting the importance of strong social ties for weathering the pandemic and racial injustices.

On the other hand, neighborhood-level challenges persist, particularly in low-income communities. My students photographed the abundance of less-expensive but unhealthy junk food (i.e., “food swamps”) and linked food insecurity to chronic diseases that increase risk for severe illness from COVID-19. They communicated how a tenuous economy and lack of affordable housing further complicate efforts to meet basic needs. Some students shared that urgent care clinics and quality health care remain out of reach for their most vulnerable neighbors.

What changes do students propose to re-invent their neighborhoods? Create good-paying jobs and support small businesses. Increase COVID-19 testing in low-income communities. Build and fund community health centers. Convert vacant buildings and strip malls to social service agencies, youth recreation centers, and affordable housing. Make neighborhoods walkable. Re-zone food swamps and support healthy supermarkets. Increase support for mental health services. Build parks in low-income neighborhoods. And the list goes on…

Your ZIP code should not determine how long you live or if you are at elevated risk for COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, or worse. We can and must do better. If given the opportunity, Americans most impacted by the current pandemic stand ready to share their experiential knowledge and visions for a better, brighter, and healthier future.

Comments