LOS ANGELES and BURBANK— What if the South had won the Civil War? That proposition lay behind my father’s frequent observation to my mother (born and raised in Norfolk, Va.) that if the South had won, she’d have been born in a foreign country! (I might have been able to claim dual citizenship, but to what good?)

But the premise of TH IR DS, enjoying its world premiere production at the Zephyr Theatre, entertains yet a third possibility: That the Civil War was never fought! That after the attack on Fort Sumter, S.C., Abraham Lincoln, in his wisdom, concluded that this flagrant act of rebellion against the federal government was insufficient to justify setting the entire country on a course of war. Instead, he allowed the Southern states to break away as the independent Confederate States of America, and the Western states became the Pacific States of America. Thus, a three-way division of the states—except that in this configuration, Virginia winds up in the original USA, not the Confederacy, whose capital is now Montgomery, Ala.

In the second play, seen the following night, The Civility of Albert Cashier, the Civil War is all too real, as we follow the exploits of the 95th Illinois Volunteer Regiment at the Battle of Vicksburg and elsewhere, focusing on one of its most valiant soldiers.

The North American Water Quality Initiative

With climate change an ever-present reality, the premise of TH IR DS is that “tomorrow” (when the play is set) a historic drought is threatening the citizens of the Confederate States. Catherine Shepard (Corbin Reid), the world’s most powerful water tycoon and prominent climate activist from the BayArea, will travel to Montgomery to finalize the North American Water Quality Initiative, a secret deal between governments to open pipelines providing the people of the CSA with clean water before it’s too late. At issue, on both sides, is how much the other can be trusted. She already has her flight to Oslo booked, where she is slated to receive a special Nobel Prize for her peacemaking and humanitarian efforts.

Playwright Ben Edlin, who based the play on a story by Deborah Aquila and himself, explains that the play “is an exploration of the ties that bind us together and the forces that pull us apart: of the hope that lies in understanding when our bitterness departs. Of the dangers we may drown in when we all decline to say, ‘I’m not sure I agree, but still, our brotherhood should stay.’ It’s a story of survival and of reaping what we sow.”

The image that we see of the Pacific and the CSA cultures is vastly divergent: one a liberal citadel of progressive thought populated by a lot of vegans, the other—well, picture what might have evolved after 150 years of racial superiority, obscurantism, deregulation, and Orwellian backwardness, epitomized by the fact that the name George Orwell is totally unknown to them. The CSA, which retained slavery for another 30 years, has literally walled itself off from the rest of the continent (with the rubble they salvaged from the total destruction of Cuba), full of spies and stockpiled with weapons. Crossing its border is like going into some paranoid isolationist nation-state. Its citizens’ pledge is not one of allegiance but of obedience.

Director Jessica Aquila Cymerman thinks of the play as “a reflection of a pervasive undercurrent in the United States right now.” But “more than an alternative history exploration, this play is a deeply human examination. What makes us believe biased truths about each other? What drives our actions, passions, joy, rage? Which issues make us go to the polls? Which ones make us bury our heads in the sand? What is it about Americans that we can hate one another, yet address ourselves as one, on the global scale? This play conveys our greatest fears as a nation that is designed to be aligned; it speaks to the sentiments of an election year. Its relevance is timely, and its message universal. Are we not better together, supporting each other, sharing resources? Especially when humanity’s next hurdle will be the elements, now is the time to learn how to band together, united.”

A cast of four is onstage, alongside Catherine. We have her coworker David Cohen (the playwright Bed Edlin), whose wife is about to give birth to their first child, and who has traveled to Montgomery for the signing, James Cross (Carlo Mancasola), a corrupt magnate as well as powerful government figure and the negotiator for the CSA side on the water deal, and his underling deal manager Steven Choi (Brian Yeun), also expecting his first child, a native of the CSA from Korean immigrant parents. Among the sharpest passages of repartee are those between the ultra-liberal Cohen and the completely educated-in-CSA Yeun, who gives as good as he gets when his righteous Jewish counterpart raises issues of prejudice.

On a video screen—for the documentary film being made about the deal and the severe conditions for ordinary working people in the dry South—we meet Derek Webster as Professor William Seward explaining the historical context of the story, reminding us that up to the moment of his inauguration, Lincoln never spoke of emancipation but only of containing the spread of slavery; homemaker and mother Patricia Todd (Tess Garrison), and her coal-miner husband Peter Todd (Éanna O’Dowd), who is visibly, audibly and deathly ill, and representative of a Proud Boys-type of suggestible mentality that’s ready to go down blindly shooting at whatever perfidy against the CSA way of life that he perceives. The widespread suspicion is that drought or no drought, the Pacific States plan feels like an updated scheme of the carpetbaggers, the Northerners who made their way South to profit off of Reconstruction.

So far so good. Finely etched characters, a plot that, a few months from now, if MAGA seizes the day, will not sound at all so preposterous, and high hopes that for the better good of all, this water deal will materialize. And then, two-thirds through the second act, the plot goes all haywire, and we don’t know what to believe anymore. Has this turned into a play within a play? It’s almost as though the playwright couldn’t finally square his circle and chose a manner of ending the play with a whole new set of issues that leave us even more confused and hopeless than before. Maybe on a second viewing, I might have come closer to understanding his intentions, but I don’t believe audiences should be treated so cavalierly, having invested considerable attention in a whole exposition that’s basically tossed aside.

Having said which, I found the acting and the direction superb. Gabrieal Griego produced the play for Last Exit Productions; Jeff G. Rack, whose work with Theatre 40 I’ve always admired, did the scenic and prop design; Derrick McDaniel did the lighting design, Joseph “Sloe” Slawinski did the sound design, Emilyna Zoe Cullen did the costumes, Andrew Marsh is credited as the composer, and Michelle Hanzelova-Bierbauer did the projection and graphic design.

TH IR DS plays through September 29 at the Zephyr Theatre, 7456 Melrose Ave., Los Angeles 90046, with performances on Fri. and Sat. at 8 p.m., and Sun. at 2 p.m. For more information and tickets see here.

Who was Albert Cashier?

The Colony Theatre in Burbank is owed a huge debt of thanks for presenting to the public the Reel Red Entertainment production of The Civility of Albert Cashier, a new musical with a book by Jay Paul Deratany, music by Coyote Joe Stevens and Keaton Wooden, lyrics by those three, choreographed by Hayden J. Frederick and directed by Richard Israel with music direction by Anthony Lucca and conductor Anthony Zediker. An earlier version was seen in Chicago in 2017, and there have been some concert readings of the score in the meantime.

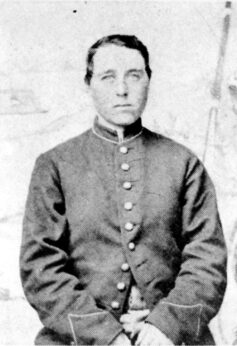

The story is a direct and straightforward one, though told episodically, with flash-forwards and backs. In August of 1862, the Civil War now having drawn out far longer than at first anticipated, 17-year-old (he was actually 18 at that point), Irish-born Private Albert Cashier enlisted in the Union Army’s 95th Illinois Volunteer Regiment and fought with valor during the Civil War, until being honorably discharged on August 17, 1865. He received a lifetime military pension in recognition of his service. But there was more to Albert than most people knew. He had a secret. This heroic American soldier was born Jennifer Hodgers, a name he adamantly refused to respond to.

The scene shifts between the battlefield, the Soldiers and Sailors Home, and a military courtroom in Quincy, Illinois, in 1911, where the authorities, incredulous that a woman could have served in the Civil War, are attempting to cancel any further pension payments. At times the younger Albert (Dani Shay) and the Older Albert (Cidny Bullens) appear together and sing to one another across the decades. As the program bios denote, Cidny (formerly Cindy) is a trans artist (female to male) himself, and Dani, nonbinary, earned a Joseph Jefferson Award nomination for Best Lead Performer in a Musical in the Chicago production, after recommending that the awards committee drop the binary “actor/actress” categories.

Because of his slight stature at only five feet, Cashier was initially assigned to be the unit’s bugle boy, but he soon distinguished himself in battle with his sharp aim against the Confederate rebels. Wounded in action, he recovers and returns to the fray. In parallel stories, other members of the regiment also have their own secrets or issues to overcome. Jeffrey N. Davis (Blake Jenner) sees himself as “different,” something of an outcast among men, eager to be Albert’s “possum buddy,” which can be read, I think, as “bosom buddy.” He admits, in fact, that he loves him, which the audience hears, of course, as a final credo of self-acceptance as a gay man. That’s not what Albert wants, however. Billy Middleton (John Bucy) is an out-and-out racist not fighting for emancipation but simply against rebellion, who is contemptuous of the unit’s Black barber/medic/surgeon H. Ford Douglas (Cameron J. Armstrong). But he comes around, especially after seeing how learned Douglas is, while Billy can’t even read or write. His death scene movingly acknowledges his senseless bias.

Douglas himself has a great deal to say about the injustice of slavery and has no doubt that this is what the war is essentially being fought over. Having treated Albert for his shoulder wound, he became aware of Albert’s reality and honorably kept it to himself. And a Black aide, Booker Curtis (Phillip J. Lewis), at the home where Cashier is unhappily housed, is a godsend to his patient, but he has an up-to-now unknown yen to get to Chicago and be himself as a musician and singer in the new ragtime vogue: his number “Chicago” is a knockout. This is a musical with truly no small roles, though they blend together in stirring harmony in their anthems of brotherhood forever.

The women’s roles are strong as well—Sattie Douglas (Fatima El-Bashir) is the wife of surgeon Douglas and is given a prominent part as his life companion. Nurse Smith (Lisa Dyson) is the classic Ratched type, who is finally humbled by men in higher positions. Abigail Lannon (Andrea Daveline) plays a wealthy estate owner, with connections in high places, who was Albert’s longtime post-war employer and friend.

“Being brave,” writes Heather Provost, Producing Artistic Director at The Colony Theatre, “may also be the courage to stand up for what is right, the strength to live openly and honestly, or the resilience to continue in the face of adversity. Albert’s story serves as a powerful metaphor for these challenges—illustrating that bravery is not always loud or grandiose. Sometimes, it is simply the act of living one’s truth with dignity and grace.”

A thoroughly commercially oriented musical with lovely lyrics and ear-pleasing songs, especially notable for its robust male choruses, Civility expresses its sentiment with a full heart. Though we hear resonances with the language and values of the mid-19th century, the real truths it voices are contemporary—equality, dignity, respect. The final chorus underlines it with the history-laden words, “The rights of one are the rights of all,” a lesson still to be fully incorporated into America’s promise.

Perhaps the dream of a just and loving post-prejudicial world is a bit kumbaya, but after all the chaos and division of recent years, a little kumbaya sure feels okay. I believe any theatergoer will feel personally honored to experience this important musical phenomenon while it’s around. I wish a very happy future for it as it pursues its future course.

Aside from those named, the cast also features Josh Adamson, Tanner Berry, Evan Borboa, Brett Calo, Gabby Dahlen, Michael Guarasci, and Jonah Robinson.

As the audience filled in, my companion and I remarked that the fixed two-level unit set surely would require the actors to do a lot of scrambling up and down ladders, which was confirmed by the fellow who happened to be sitting next to us, Mark Mendelson, who did the scenic design. The lighting design is by Andrew Schmedake, costume design by Rebecca Carr, and sound design by Robert Ramirez. Projection design is by Gabrieal Griego, properties designer is Michael O’Hara, and assistant director is Aaron Camitses.

The regular performance schedule is Thurs., Fri., and Sat. at 8 p.m., and Sun. at 3 p.m., through September 22. There will be no performance on Fri., Sept. 13, and an added performance on Sat., Sept. 14, at 2 p.m.

For further information and tickets go to the company website. The Colony Theatre is located at 555 N. Third St. (between Cyprus and Magnolia) in Burbank 91502. Free onsite parking is available.

We hope you appreciated this article. At People’s World, we believe news and information should be free and accessible to all, but we need your help. Our journalism is free of corporate influence and paywalls because we are totally reader-supported. Only you, our readers and supporters, make this possible. If you enjoy reading People’s World and the stories we bring you, please support our work by donating or becoming a monthly sustainer today. Thank you!