LOS ANGELES— Qui Nguyen’s Vietgone, a contemporary interpretation of the classic boy-meets-girl story (seen Oct. 26), is an American-born playwright’s intimate confrontation with the immigrant experience, based on what he knows (and fantasizes) of his Vietnamese mother and father. It’s unimportant how much of it conforms to historical truth, which is always a moving target subject to discussion anyway. The characters he creates are alive and real, bold and sassy, emblematic and surreal, conflicted in the general ways immigrants are challenged, and particularly in the way Vietnamese immigrants have been received in America.

Every once in a while, here in Southern California, where the largest concentration of Vietnamese immigrants has settled, a kerfuffle breaks out when for some reason, such as the visit by a dignitary from Vietnam or a young people’s group wanting to act contrary, the modern-day Vietnamese flag is displayed in public. It usually doesn’t last long—just long enough to see it replaced by the former flag of the South Vietnam republic, which disappeared 43 years ago.

The play addresses the generational differences between the first refugees who started arriving immediately upon the fall of Saigon on April 29, 1975, and have continued in waves ever since, and those who have made their peace with the emergence of a unified socialist Vietnam in the wake of the U.S. imperialist war. Some Vietnamese Americans are capable now, as they were not before, of traveling back to their homeland for tourism, family visits or to pursue business opportunities.

East West Players (EWP), the nation’s longest-running professional theater of color in the country and the largest producing organization of Asian American artistic work, includes Vietgone in its Los Angeles premiere as part of “Culture Shock,” a 53rd anniversary season that is about reframing the “outsider” narrative.

Unlike refugees or immigrants from other socialist lands in Eastern Europe or from Cuba, who were welcomed with open arms to the United States as political “defectors,” Vietnamese immigrants were often seen as “different” owing to racial characteristics. Assimilation came uneasily: Many nativist Americans simply bundled them into their generalized contempt for Asians of any nationality, whom they saw as taking American jobs both in the U.S. and in outsourcing destinations such as China, Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines. It was a “BFD” (to use V.P. Joe Biden’s construction) when the first Vietnamese immigrants were elected to office. Now there are several in California and elsewhere.

Described in the New York Times as “a raucous comedy” and in Rolling Stone as “a wild, enjoyable ride,” Vietgone is at the same time a poignant inquiry into the hearts of individuals who refuse to be defined by expectations.

The director, San Francisco-born Filipino-American Jennifer Chang, speaks of the play as “an American story: a story of immigrants, of musical theater via hip-hop, of refugees, of assimilation, of war heroes, a buddy flick and bromance, a ‘rom-com,’ and a celebration of the Asian man.” And I would add, the Asian woman as well.

In a 2017 interview with American Theatre, playwright Qui Nguyen says, “Everyone deserves a chance to see themselves on stage. With Vietgone, I wanted to address the huge lack of sexually powerful, driven, and complex Asian-American male and female characters on our stages. I wanted to see a sexy Asian male and a sexy Asian female be sexy for something other than being ‘exotic.’ And I wanted to make something that a young ‘yella’ kid could see and feel proud of themselves after seeing it…. That’s why all my female characters end up being badasses.”

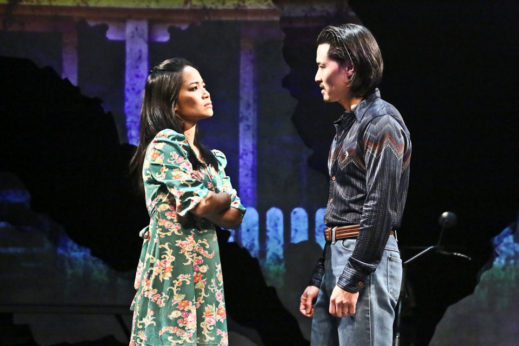

What audiences will see are no cleaned-up, idealized versions of Nguyen’s Vietnamese relations. They are complex and interesting. The story revolves around Quang (Paul Yen) and Tong (Sylvia Kwan), refugees who find one another at Fort Chaffee, a relocation camp near Fort Smith, Arkansas. Each, already 30 years old when we meet them, has their own reasons for coming to America in 1975.

In Quang’s case, he was fleeing for his life, as he was a captain in the South Vietnamese forces and feared for his life were he to be caught by the victorious Viet Cong. There’s a funny but telling scene in Act 2 when Quang, trying to return to Vietnam to be a father to the two young children he left behind, encounters a dope-smoking husband-and-wife hippie couple on the road. Hippie Dude tells him, quite earnestly, how sorry he is for what the U.S. did to Quang’s country and how he worked so hard to end the war. But that is not Quang’s perspective at all: He had earlier trained as a helicopter pilot in the U.S., and regarded the Americans as saviors from Communist murder, rape and humiliation. “Many of them died so I could be here.” If Quang is the male protagonist of the play, with Asian agency, he appears to have no clue that his diehard service in the South Vietnamese armed forces was itself in the larger service of American imperial and Cold War designs (from my Hippie Dude-sympathetic point of view, I will admit).

Tong has her own backstory, part of which entails leaving behind the memory of an earlier boyfriend, as well as a younger brother, while being shamed into bringing her hard-edged mother to America with her. Much of the emotional expression in the play is told through rap lyrics somewhat à la Hamilton. The surprisingly bawdy “slut walk” Tong says, “Love is just some bullshit story / A poetic veneer why we get horny…I just needed your dick to scratch a little itch / if you want to fall in love, go find some other bitch…I’m not some little girl dreaming for her prince / I can save my own kingdom, I’m a bad ass bitch!”

The fearless Vietgone takes audiences on a rocky 1970s trip across the American landscape with a punchy soundtrack and elements of pop culture, comics, ninja fighters, many different Asian characters and a host of American stereotypes (such as a lovelorn GI at the camp and a rebel flag-carrying Southern redneck). The two leads play only themselves, but the three other performers each take on multiple roles. Jane Lui is especially comical as Tong’s mother, among other parts. Scott Ly is persuasive as Quang’s rom-com buddy Nhan. And Albert Park plays Bobby, a lovesick blond American GI, the aforementioned Hippie Dude, and the Redneck Biker.

It’s a sly comment on Nguyen’s part to have the two masked ninjas who intervene in a fight between the two buddies and the Redneck, interceding as hired mercenaries, as it were, on the Redneck’s side. That may be his way of commenting on the role that Quang was actually performing in the 1960s and ’70s on the global map, which nevertheless does not detract from the integrity of the character. The fight scene alone, staged by Thomas Morinaka and Aaron Aoki, is worthy of applause—and received it. The whole show is vivacious and energetic.

Vietgone sets a high-water mark in Asian-American theatre. Without judgment or sentimentality, it exposes the raw nerves of characters in distress and transition, people who have lost everything and must start again halfway across the globe. If there is love here—and there is—it is tough and hard-won. As Tong’s mother admits, “Love doesn’t make you weak. It makes you strong during the fight.”

Aside from the actors and director Chang, the creative team also includes Shammy Dee as composer and music director, Kaitlyn Pietras and Jason H. Thompson for scenic and projection design, Tom Ontiveros for lighting, John Zalewski for sound design, and Stephanie A. Nguyen for costumes.

Vietgone is one of the highlights of the season so far. The full playscript of Vietgone appears in print in the February 2017 issue of American Theatre.

Vietgone is staged at the David Henry Hwang Theater at the Union Center of the Arts at 120 Judge John Aiso St., Los Angeles 90012. Performances through Sun., Nov. 18 are Thurs. to Sat. at 8 pm, and 2 pm matinee shows on Sat. and Sun. (exception: no 2 pm show on Sat., Nov. 17). A Pay-What-You-Can performance is on Thurs., Nov. 1 at 8 pm.

Tickets may be purchased online at eastwestplayers.org or by calling (213) 625-7000. Be sure to mention any wheelchair/accessible seating needs. Student, senior, and group discounts are available.