2019 ILCA PW Winner, THIRD PLACE Saul Miller Award, Political Action

DETROIT—In Michigan, it’s the issues, not the candidates, driving people to the polls.

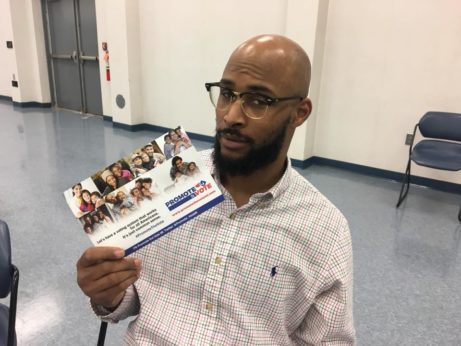

With voter suppression in myriad forms sweeping the country, a counteroffensive in Michigan, called “Promote the Vote,” gives the state’s voters the opportunity to add an amendment to the state’s constitution to ensure that every citizen can vote and that every one of those votes is counted. Enthusiasm for the measure has driven ten thousand volunteers to step up for door knocking and phone banking, says Brandon Jessup, deputy director of Promote the Vote.

With voter suppression in myriad forms sweeping the country, a counteroffensive in Michigan, called “Promote the Vote,” gives the state’s voters the opportunity to add an amendment to the state’s constitution to ensure that every citizen can vote and that every one of those votes is counted. Enthusiasm for the measure has driven ten thousand volunteers to step up for door knocking and phone banking, says Brandon Jessup, deputy director of Promote the Vote.

The ballot initiative polls well among not only Democrats but also Republicans, among rural as well as urban voters, because its provisions make sense to all, says Jessup. According to the Detroit Free Press, support across the state is upwards of 70 percent.

Jessup emphasizes that Promote the Vote is a nonpartisan issue and supporters, which include much of the labor movement and church community as well as civic organizations such as the ACLU, go to great pains to present it that way statewide in a state that is often seen as divided politically as “urban vs. rural.”

The campaign’s literature highlights that its passage would ensure that military service members get their ballots in time for their votes to count. Besides military service members, others have been personally touched by voting issues, Jessup points out. “Same day registration is an issue on campuses across the country,” he says. “But in Michigan, campus polling places have been closed down over the last 15 or so years.”

In 2016, Donald Trump won Michigan’s 16 electoral votes with a razor-thin 11,000 vote margin.

The proposed constitutional amendment, which will appear on the Nov. 6 ballot as Proposition 3, includes provisions for Election Day registration, access for all voters to absentee ballots, automatic registration in interactions with the Secretary of State’s office, an option for straight-ticket voting, and an automatic audit of the vote.

While other states offer some of these provisions in their legislature-passed statutes, Michigan will be the first to lock them in the state’s constitution, according to Jessup.

Michigan’s Republican-controlled state Legislature recently eliminated the option of straight-ticket voting. Voting rights activists fear two negative results: long backups of voters at the polls and lower attention to down-ballot positions.

More People’s World coverage of voter suppression efforts across the country:

> Rampant voter suppression underway, with Black voters the chief target

> Voter suppression: Not just in the South, not just ID laws

When it comes to guaranteeing voter rights, activists in Michigan are playing the long game, says Jessup, who is very familiar with the history and impact of voter suppression in that industrial state.

Proof of the potential for a ballot proposition to mobilize communities came in 2011 and 2012 during a campaign to repeal the state’s Emergency Management Law. This law had allowed for elected mayors and city councils in Michigan to be replaced by political appointees, Jessup recounted.

The Emergency Manager law, passed by the big-business-dominated state Legislature, resulted in lost pensions and the Flint water crisis. Activists then gathered 267,000 signatures for a ballot measure to repeal the law. They didn’t get funding from broad networks of support, but they gained experience in ballot initiative campaigns and an appreciation of their mobilizing potential. That ballot initiative passed but was effectively reversed months later by the state Legislature.

In this year’s electoral cycle, 400,000 signatures were gathered to put Proposition 3 on the ballot. Jessup points to some other factors building on the experiences of the 2012 campaign. “Promote the vote has broad appeal,” he explains. “It’s a measure everyone can catch hold to.” After all, “Everyone votes, across all generations.” Besides concerns of students and military members, “Every year 200,000 people fall into a window—they did register, but were registered at the wrong place,” says Jessup.

The current arbitrary deadline of 30 days to correct registrations of folks who have changed addresses does away with the opportunity to vote for these 200,000 citizens. With modern technology capable of updating records instantaneously, there is no justification for not allowing people to correct their registration and participate in the process, Jessup argues.

This campaign is a collaborative movement in the way the conversation is being framed, Jessup says. Women have emerged as leaders in the movement. Young people took the initiative—every single college in the state had petitions circulating. And young people of color have played a special role in initiating and leading both on campuses and in communities. Community organizations are the crux of the education campaign.

Jessup, 37, describes himself as a “data scientist.” He has strong views on how technology can and should be used in political campaigns. Social media is not an answer in and of itself, though, he says. While people have discussion in their online communities, those conversations are not random, they’re with people they have relationships with—and influencing people is still based on personal ties. “Organizing is relationship-based,” he says. “Social media comes into play in supplementing how we distribute the message.”

The focus of training young people in this campaign is not about organizing techniques, but on the message itself. Jessup sees putting the emphasis on creating leaders by educating activists about the issues—“wherever two or more meet”—whether it’s a gathering after church services, in a union hall, or at a table on a campus.

Another Michigan ballot initiative is also related to the voting process. Proposition 2 would address the fact that Michigan is one of the most gerrymandered states in the country, says Mickey Bennett, from the Speakers Bureau of Voters Not Politicians. Prop. 2 would create an Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission to draw new districts after the 2020 elections for Congressional and state legislative seats.

“No party should be able to create districts with safe seats where the outcome is pre-determined,” says Bennett. Bennett says adoption of this amendment would remove the obvious conflict of interest inherent in a system where state legislators draw their own districts. “Democracy is thwarted,” he continues.

The measure sets up a several-layered process to create these committees, a process complex enough to prevent their manipulation by partisan forces, Bennett explains. Voters would be able to volunteer for these committees, and among those volunteers, a lottery would randomly pick 60 Republicans, 60 Democrats, and 80 unaffiliated voters. Elected officials, their appointees, families, and lobbyists would be ineligible.

In the next stage of the process, state party leaders may eliminate up to 20 of the 200 selectees, similar to the way that both sides have peremptory challenges in picking a jury. In the last step, a final draw from the remaining pool would produce a commission made up of four Democrats, four Republicans, and five unaffiliated or third-party voters. This citizen committee process is templated off of a procedure currently in place in California, says Bennett.

The retired small business owner says that his personal voting history includes voting over the years for candidates of both parties. But the current gerrymandering, he says, “has created a legislature that responds to a tsunami of money flooding in and drowning our voices.”

The measure is also polling well across the state’s 83 counties. The Detroit Free Press reports it is favored by voters 59 to 49 percent in every category. It is opposed by Michigan’s Chamber of Commerce and the Republican Party, but even Republican voters support it 48-44.

The gerrymandering resulting from the status quo gives big business control of the state Legislature, says Bennett. “Our local interests are submerged to lobbyists,” he says, citing the examples of raw sewage pumped into the Clinton River and a state giveaway to the Nestle Corporation.

Nestle pumps half a million gallons of water every day from the White Pine Springs well in the Great Lakes Basin. It’s a win-win for the giant multinational, but lose-lose for Michigan residents: Nestle which uses the water to fill its Ice Mountain brand bottles at virtually no charge, but makes big bucks selling bottled water around the country, including to residents of Flint, Michigan. Those Michiganders hold the gerrymandered state Legislature responsible for the fact that their local water is no longer drinkable, autoworker Steve Noffke told People’s World.