Trump launched the so-called “China Initiative” in 2018 to target scholars who worked with Chinese colleagues on science-related projects. Since then, more than a dozen U.S.-based scholars have been arrested, jailed, put on show trials, and harassed by federal authorities. Notably, former Trump aide Steve Bannon’s comment that there are “too many Asians in Silicon Valley” prompted the initiative.

Accusations of terrible crimes, like spying or stealing millions of dollars, have ended up reducing to relatively minor charges, such as the failure to report some relationships with Chinese entities on applications for federal grants. Prior to the “China Initiative,” such errors on disclosure reports were typically regarded for what they were: accidental oversights on a complex application process that can be easily corrected without punitive measures.

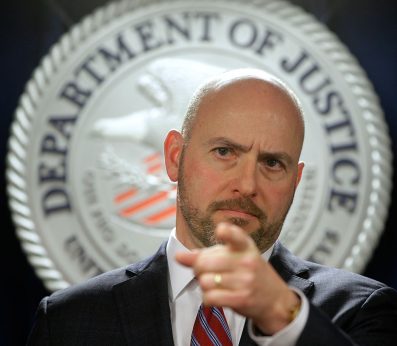

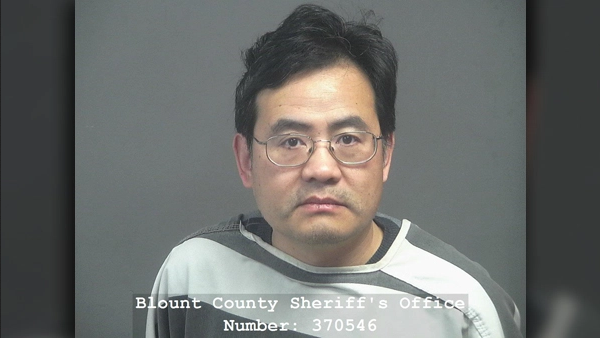

Two recent cases highlight the racist motives of the China Initiative and the abuses by federal authorities. In March 2021, Trump-appointed U.S. Attorney Andrew Lelling ordered the arrest of MIT scientist Gang Chen for wire fraud and an array of other serious charges with large prison sentences. Earlier this month, a hung jury led to a mistrial in the court case of Anming Hu, a University of Tennessee-Knoxville scientist arrested on trumped-up charges—one of the first victims of Trump’s “China Initiative.”

In Chen’s case, his colleagues have rallied to his defense, even paying for his legal costs. Abusing his power as U.S. Attorney, Lelling was ultimately compelled to reduce the charges to failure to report activities related to sending letters of recommendation on behalf of students in China. Chen’s colleagues describe this activity as a normal part of any faculty member’s job.

For his part, after being fired as U.S. Attorney by the incoming Biden administration, Lelling continued to bluster that his actions were meant as a warning to academics who don’t accept the U.S. government’s anti-China policy, echoing the ongoing attack on university professors who teach critical race theory.

The recent hung jury trial of Anming Hu has exposed the “China Initiative.” Hu, a citizen of Canada and science professor in Tennessee, helped win the university a huge NASA grant—until FBI agents began to investigate his ties to China. They spent nearly two years interrogating Hu, following him, and even reportedly pressuring him into becoming an FBI informant spying on his colleagues in China.

This latter detail hasn’t yet been reported in other cases, but it is common for federal agents to use the threat of “throwing the book” at someone unless they turn informant. This aspect makes some observers question whether or not the “China Initiative” is more about recruiting spies than it is about catching them.

In court testimony, FBI agents admitted they lied to Hu and his employers, which ultimately got him fired. They admitted they had no evidence for the charges with which they threatened him. Ultimately, they charged him with failing to report work for which he was paid a small amount of money. His defense team noted that the work was unrelated to the NASA project and was not even asked for on complex disclosure forms. The university had approved Hu’s application but has chosen not to publicly defend him.

Earlier this month, a jury failed to find Hu guilty, and one juror reportedly said the whole case was ridiculous.

U.S. anti-China policies in historical perspective

Accusations of Chinese spying in the U.S. are not new. After the 1949 Chinese Revolution, U.S. failures in the Korean War, and two international scientific investigations that exposed U.S. use of germ warfare in North Korea, the U.S. government was desperate to reorient international opinion against China.

In 1955, a U.S. “diplomat” named Everett Drumright stationed in the British colony of Hong Kong had a bright idea. The British government had just completed a massive round-up, imprisonment, and deportation of thousands of Chinese people in Hong Kong who opposed British colonialism and supported reunification with China. British officials had suppressed newspapers, banned political parties, and enforced only pro-U.K. views in the public square.

Drumright, who was virulently anti-Chinese, decided that similar forms of oppression could be implemented in the U.S. to enforce loyalty and to extract detailed information about mainland China. U.S. spies frequently complained that Hong Kong and Taiwan were the closest they ever got to mainland China, creating a vacuum of information about it.

As historian Mae Ngai has shown in her book, Impossible Subjects, Drumright wrote a report for the State Department claiming that Chinese residents of the U.S. had universally entered illegally or under fraudulent circumstances. Further, they composed a vast network of spies regularly reporting to the Chinese government. He suggested a coordinated effort by immigration authorities and federal investigators to be mobilized against them.

No one in the State Department really believed that wild theory, but in the McCarthy era, the failure to get out in front of those rumors could be a public relations disaster for President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s re-election chances.

Basically, racism drove U.S. policy. The government created the Chinese Confession Program, which offered amnesty and permanent status to Chinese people who participated by confessing their illegal or fraudulent status.

During the “exclusion” era (1882-1943), most Chinese people were barred entry unless they were a business owner, a student, or could prove they were the son or daughter of a U.S. citizen or permanent resident. Scholars estimate that in these 60 years perhaps 300,000 Chinese people entered the country under these circumstances. Many did so through falsified documents related to the latter.

During World War II, however, China had been a valuable partner of the Allies, and the exclusion law was lifted.

From 1956 into the early 1960s, more than 11,000 Chinese people were interrogated and coerced into admitting their true family histories. In true McCarthyite fashion, they were also forced to identify others who may have also falsified their immigration stories, extending investigations to thousands of others. In the process, Taiwan-linked Chinese associations provided federal agents with long lists of members who might be targeted, hoping they would be spared repression.

No Reds under the bed

Federal authorities unearthed none of Drumright’s spies. But people who were supportive of China, active in their labor unions, advocates of civil rights, or opposed the Korean War were silenced. Many retreated into privacy and refused to take part in civil society. Even people who hated the Communist Party were not spared as part of this new iteration of the “yellow peril.”

As scholar Heidi Kim, in her recently published book Illegal Immigration/Model Minority shows, the era’s policies effectively damaged families, eroded personal relationships, disrupted communities, and scarred Chinese-Americans (of whatever political affiliation) for the next two generations.

Soon after the program was launched, new and improved U.S.-authored, anti-China propaganda began to appear in Hong Kong, Taiwan, Macau, Singapore, Malaysia, and other countries with large overseas Chinese populations. According to scholar Xun Lu, U.S.-funded Voice of America radio broadcasts, newspapers, pamphlets, and books containing details about events in China that could be twisted to fit U.S. propaganda goals overwhelmed pro-Chinese sentiments and even objective criticism of the U.S. and British roles in East Asia.

The germ warfare issue was off the table and buried under the rug. Political repression and mass killings in Hong Kong, South Korea, Philippines, Indonesia, and Taiwan backed, paid for, and often orchestrated by the U.S. and the U.K., were displaced from the headlines. U.S.-backed military dictatorships in South Korea, Philippines, Indonesia, and Taiwan continued through the rest of the Cold War but were largely unaddressed by Western “human rights” circles.

Suppression of pro-China voices was so effective that in Hong Kong many supporters of the U.S. and U.K. sought permanent entry into the dwindling British “empire.”

Today’s “China Initiative” is playing a similar role in U.S. policy. Under Trump, it motivated anti-China and anti-Asian violence and hatred. Under Biden, we see, so far, no change in this direction other than a few kind words about Americans of Asian descent who are being abused because of such policies and a hate crimes law that appears to provide police and federal agencies with more resources.