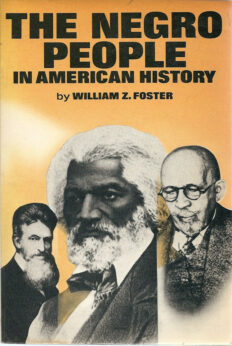

Editor’s Note: Feb. 25, 2021, marks the 140th anniversary of the birth of William Z. Foster. One of the most well-known figures of early 20th century labor history, Foster spearheaded the drive to organize the packinghouse industry during World War I and led the Great Steel Strike of 1919. He later joined the Communist Party and rose to leadership in its ranks. As the party’s presidential candidate alongside Black leader James W. Ford in 1932, Foster tallied over 100,000 votes. He was also a pioneer in the fight against racism in organized labor and to integrate trade unions, which for so long persisted in downgrading or ignoring the struggles of Black workers. In this article, biographer Arthur Zipser discusses Foster’s role in the fight to bring full equality for Black workers in the U.S. labor movement. It is excerpted from his 1981 book, Working Class Giant: The Life of William Z. Foster, from International Publishers.

It can hardly be said that Bill Foster was born into the struggle for racial equality. The sordid Philadelphia slum in which he grew up was the turf of a youth gang called The Bulldogs, most of whom, like Foster, were of Irish-American nationality. They showed scant hospitality to “aliens” who wandered into their territory. In the case of Black people, the ban was total. Those who ventured there could expect a rough reception.

Foster left the old neighborhood when he was about 20 years old and began a search for work which soon took him to Florida, where he found work in a sawmill. Six Black workers and eight whites lived in segregated misery in this lumber camp. Here Foster first witnessed an episode of racist terrorism. The noisy approach of nightriders alerted the Black workers. They fled into the woods where they remained all night. The leader of the gang noticed Foster’s Northern mode of speech and assured him menacingly that “if a Yankee minds his own business he is almost as good as a dog.”

Most American Federation of Labor unions excluded Blacks from membership in those days, and the Socialist Party, to which Bill Foster belonged, was permeated with white chauvinism. Foster left the SP in 1909 and joined the Industrial Workers of the World. The IWW was distinguished from most other labor organizations of the period by its anti-capitalism, its industrial unionism, and its willingness to accept as members the young, the unskilled, the female, and the non-white.

Foster soon broke with the IWW because of its dual-union policy which isolated the militant left from the mainstream in the AFL. He became a member of the Railway Carmen’s union (AFL) in Chicago, built a cadre of activists around himself, and before long played a leading role in Chicago’s labor movement.

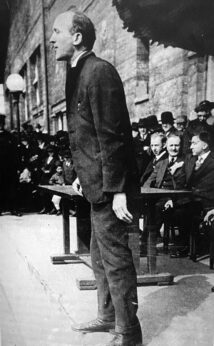

In July 1917, Foster conceived a plan to bring the huge open-shop meatpacking industry into the union fold. Using the key Chicago area as a base, he rapidly achieved a federation of 12 local unions having craft jurisdiction and formed a Stockyards Labor Council. The first meeting of the council decided to place primary stress on signing up the unskilled majority of Chicago’s 60,000 packinghouse workers.

Most Black workers were barred from the craft locals and from the skilled trades, but the unskilled and semi-skilled were now made welcome in the rapidly growing locals of the Butcher Workmen. Chicago soon had the largest African-American trade union membership of any U.S. city.

The harshly oppressed packinghouse workers were being sweated to produce food for the Allies of World War I. Foster’s bold organizing tactics evoked a sensational response. In packing centers across the country, tens of thousands flooded into the federated unions.

In less than a year, Foster and his group of militants brought unionism to an entire mass-production industry—and in a single great drive, 25,000 Black workers became union members. In 1919, when “race riots” occurred in Chicago, the Stockyards Labor Council adopted a resolution to expel any member who refused to accept Black workers on a basis of equality.

William Z. Foster’s next move was to organize the giant open-shop fortress of steel. His efforts brought 365,000 workers into the AFL and out on strike across the country in 1919. Black workers had always been barred from the craft unions, which were now federated in the steel strike committee. This fact helped the steel trust to break the strike. Writing a postmortem in 1920, Foster showed how this racist exclusion policy played into the hands of the steel bosses.

Foster joined the Communist Party in 1921, about two years after its founding. In 1922, the CP made a partial break with a position it had carried over from its left-wing Socialist forebears. The left had traditionally viewed the question of African-American rights as only an aspect of the general working-class question. But now it was recognized that Black people had special demands as a people. In 1928, and over the years since the Communists developed an advanced position which takes into account the national group aspect of the Black liberation question.

Foster was founder of the Trade Union Educational League (TUEL), which in 1924 demanded that “Negroes must be given the same social, political, and industrial rights as whites, including the right to work in all trades, equal wages, and admission into all unions….” This stand put the TUEL far ahead of all other labor organizations in the struggle for the rights of African Americans.

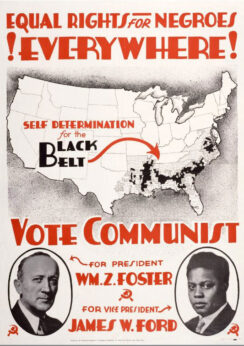

Foster was the Communist candidate for president in 1928 and carried his campaign deep into the South. There, Art Shields, veteran political reporter, heard him “lashing disfranchisement, lynchings, and peonage in a hall in Atlanta while racist cops stood at the door.” Foster again ran for president in 1932. This time his running mate for vice president was James W. Ford, a Black leader. This introduced a new symbol of Black-white unity into the sphere of political campaigning.

In the early 1930s, the Trade Union Unity League, successor to the TUEL, carried on struggles which paved the way for the great advances of the Congress of Industrial Organizations. These struggles included a bitter coal strike in Harlan, Kentucky. Historian Theodore Draper (not a friendly critic), reviewing the stubborn insistence of Foster’s forces that Black and white should eat together in the same soup kitchens, said, “It is fair to say that only the Communists in that period…would have taken such a firm stand on this issue.”

On his 80th birthday, Feb. 25, 1961, William Z. Foster was a patient in a sanatorium on the outskirts of Moscow. His severe health problems called for a level of care that was available to him only as an honored guest of the Soviet Union. In this way, the last half-year of his life was eased by maximum attention and by a friendly and protective atmosphere.

On his last birthday, a surprise party banished, insofar as possible, the woes of illness, and Bill Foster was delighted to have a distinguished list of visitors to wish him well. Premier Nikita Khrushchev was there and so were Frol Koslov and other Soviet leaders. The Russian Civil War hero Semyon Budyonny and the writer Boris Polevoi were among the visitors.

Perhaps most pleasing of all to Bill Foster was the presence of his dear friend Paul Robeson. Twenty years before, at Madison Square Garden, on the occasion of Bill’s 60th birthday, Paul had honored him singing Marc Blitzstein’s “The Purest Kind of a Guy,” a song which might have been written with Bill Foster in mind—and probably was.

The presence of the great baritone on the occasion of Foster’s birthday might have stood as a symbol of the struggle for unity of Black and white to which both men had contributed mightily in the course of their lifetimes.