The summer of 1922 was gearing up to be dangerous for the U.S. ruling class. Over half a million coal miners were striking for an honest living, nearly 400,000 hardworking railroad shopmen walked off the job, and 200,000 of America’s suppressed textile slaves picketed in opposition to capitalist cuts in their meager wages.

To better respond to the needs of the ever-more-militant working class, a political gathering was called. Later referred to as the 1922 Bridgman Convention, this assemblage brought together both the underground and public sections of the U.S. Communist movement. While the Communist Party of America was still illegal, the Workers’ Party was both openly recruiting and publishing. Members gathered in Bridgman, Michigan, to debate and vote on a resolution to either maintain the underground portion of the CPA or merge it with the public Workers’ Party.

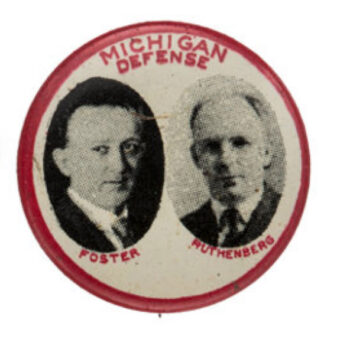

Another arm of the communist movement also sent delegates to the convention. Called the Trade Union Educational League, it sought to radicalize already existing trade unions and their members. William Z. Foster, the leader of the TUEL, was a passionate firebrand for the U.S. working class. Known for his uncanny ability to organize where other labor unions had failed, Foster and his fellow TUEL leaders were welcomed at the Bridgman Convention.

On Aug. 17, 1922, the convention was officially called to order. Francis A. Morrow, a Department of Justice informant, disguised himself as a delegate from New Jersey. It wasn’t long before federal, state, and local officials raided the convention. Within days, organizations of every kind responded to the “red” raid. The local county Republican Party passed a resolution condemning the convention. The nearby American Legion unit proudly published a sharp denunciation of the “reds.”

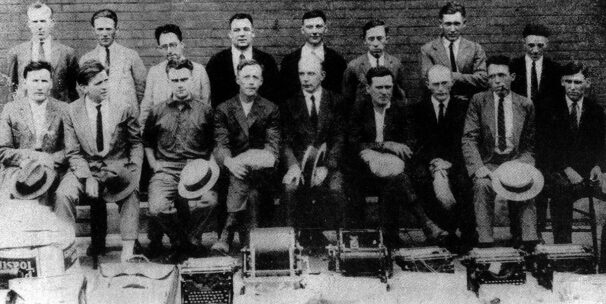

In the end, 32 individuals were arrested. Each faced four charges of advocating the theory of syndicalism and “assembling with” groups advocating for these beliefs. Because such charges had been crafted by capitalist lobbying organizations, the penalties were severe. Each man could receive up to 40 years in prison and, in today’s money, a $350,000 fine.

The assigned judge, however, could see the legal insanity of the DOJ’s charges and excused all but one: that of “assembling with” groups advocating for theories of syndicalism. The trial quickly became a constitutional battleground for freedom of speech and assembly.

Foster was the first to be put on trial. Hinting that Foster had revolutionary tendencies, the prosecutor began jury selection by asking each potential juror, “Do you realize that the Declaration of Independence is not a part of the law of this land? And, you realize further…that the fundamental right of the American people to revolution…expressed in the Declaration of Independence is not a part of the law?”

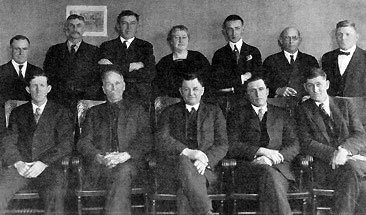

All those picked for the jury answered “yes” to the question. In the end, the wife of a large local factory superintendent, a non-union railroad flagman, a grocery store clerk, and nine farmers were selected for the jury.

The prosecution was led almost entirely by the DOJ and rested its argument on Morrow’s informant testimony. When the defense opened, they asked Morrow if he had ever been a communist before joining the DOJ. Open laughs and snickers filled the courtroom. Morrow denied the allegations as quickly as they came. Next, the defense presented evidence that Morrow had actually been an organizer for the Communist Party in Philadelphia!

The prosecution furiously objected to the evidence, but the judge allowed the defense to submit proof of their claim. The defense showed multiple CPA checks with Morrow’s signature listed as “Treasurer.” With this, the prosecution’s attack plan crumbled. Their own informant-turned-witness was no longer reliable.

The trial lasted nearly four weeks. The prosecution, now collapsing to their backup plan, lectured the jury for endless hours on why some groups of Americans should not be allowed to assemble. Conversely, the defense sought America’s founding documents for aid.

Foster would later say, “Our attorneys laid especial stress upon the right of revolution always inherent in every people, calling to their aid the Declaration of Independence to make the proposition clear.”

When the closing arguments came, the prosecution asked, “whether they were going to follow Washington and Marshall or Lenin and Trotsky, Lincoln or Marx, Christ or Pilate.” The defense, instead of resorting to such lowly childish rhetoric, relied on the Constitution’s simple “right to the freedom of speech and assemblage.”

The jury deliberated for 31 hours. Over 36 ballots would be taken. On each ballot, the jury was split six to six. It was the wife of the factory superintendent, the grocery store clerk, and four of the farmers who sought acquittal for the communists. With a hung jury, the charges were eventually dropped against Foster. In the months following, only one other of the 32 originally charged would face trial.

Minerva Olson, the only woman on the jury and wife of the factory superintendent, became an outspoken advocate for the communists’ civil liberties. She said to one newspaper, “I could look away from the [courtroom] as the trial went on and see conflicting forces fighting for mastery of human rights. This trial was far bigger for me than merely determining whether Mr. Foster [was] guilty or not guilty…”.

A hundred years later, Ms. Olson’s words still ring true. Now more than ever, there are dominating “forces fighting for mastery of human rights.” On one hand, is the employing class, and on the other hand, is the working class. Today, the top 10% of the employing class hoards over 76% of all global wealth while the bottom 50% holds only 2% of the combined wealth. The incomes of the employing class have risen nearly 9% since 1995, while the working class has only experienced a 3% increase over the same period. Additionally, far from being equitable, women only account for 35% of global incomes.

It has never been more clear that we live in a world where the employing class and the laboring class have nothing in common. For these reasons, the working class cannot let the employing class become the masters of human rights. There has never been a more crucial time for workers everywhere to assemble and speak out.

Around the world, the labor movement is expanding. Thousands of angry Starbucks workers are organizing for wage dignity. Almost 10,000 John Deere workers went on strike to win a bargaining agreement for a healthy six-year pay boost. Amazon workers are rapidly waking up and fighting America’s second largest employer. Nearly 250 million Indians recently went on a mass strike for simple demands like grain rations, direct poverty payments, and broader labor laws. Millions of workers in Myanmar courageously went on strike protesting the military takeover of their country. The examples could go on and on.

No matter where you look, it is clear that when the working class assembles and speaks out, the employing class is forced to listen. This has always been and will always be how the working class becomes the master of human rights.

Read more about the Bridgman Convention and the Foster trial:

“The Trial of William Z. Foster” by Robert Minor

“The Michigan Raid” from The Worker

“On Trial in Michigan” by William Z. Foster

“The 1923 Foster Trial” from The Reports of the WPA Press Service