A newly released CD, Yiddish Glory: The Lost Songs of World War II, includes the wartime Soviet leader’s name in at least five out of 17 tracks (there are 18, but one is a reprise), and each time he is heaped with thankful praise. The 1945 “Nitsokhn lid” (Victory Song) by Kh. Urintsov ends: “Drink yet another l’chaim [toast] for the Red Army

And give a toast to them all

That they should be healthy and well,

And toast the comrade Stalin,

May he have many years before him,

Because in the whole wide world

There is no other like him!

Americans generally have little appreciation for the fact that the Soviet Union bore the brunt of the Nazi behemoth. An estimated 25 million Soviet citizens lost their lives in what from their point of view they called the “Great Patriotic War” against the fascist German invaders. According to Russian-born musicologist Anna Shternshis, some 440,000 Soviet Jews fought in the Red Army, and of those, 140,000—approximately one-third—were killed. Of the often cited 6 million Jewish martyrs in the Holocaust, 2.5 million (that is 5 out of 12) were murdered in the European part of the USSR—900,000 in Ukraine alone.

Many people are unaware that the Soviets took extraordinary measures to evacuate large numbers of Jews—1.4 million, both Soviet citizens and refugees—from the vulnerable western Soviet republics and transport them to Soviet Central Asia and Siberia, where they survived. (I translated the memoirs of one such person, a Polish Jew by birth, whose immediate family survived the war in those areas far from the Nazi reach.)

The Jews well knew whose side Stalin was on, and they were on his! This CD marks a pronounced contrast to City of the Future, a CD I produced a few years ago, also of Soviet Yiddish songs, but written in 1931, before Stalin had completely consolidated his rule. In those songs, with lyrics by many prominent Soviet Yiddish poets, not once is the name Stalin mentioned.

A tragic story with a redemptive end

Even as the war was still raging, a group of Soviet Yiddish scholars undertook an ambitious project of preserving Jewish culture of the 1940s while and soon after it was created. Linguists, folklorists, and historians joined to record stories, anecdotes, poems and songs by Jews who lived through the most painful passage of their history. They were Holocaust survivors, women working in factories on the home front, Jewish Red Army soldiers, evacuees to Central Asia, husbands and wives, lovers, grieving children.

Soviet ethnomusicologists from the Kiev Cabinet for Jewish Proletarian Culture, led by Moisei Beregovsky (1892-1961), recorded hundreds of new Yiddish songs, tunes that detailed the Soviet Jewish wartime experience. Beregovsky and his colleague Ruvim Lerner (1912-1972) hoped to publish an anthology of these songs, but the project was never completed as Beregovsky was arrested for “Jewish nationalism and anti-Soviet activities” in 1950, at the height of Stalin’s post-war anti-Jewish purge that culminated on August 12, 1952, with the execution of 13 prominent Jews, some of whom had been leaders of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee during the war. The documents were confiscated and sealed. The scholars died thinking that their work had been lost and destroyed.

Such had the fate of the Soviet Jews changed. Although later in the 1950s the executed Jews were “rehabilitated” and some attempts were made to resuscitate Yiddish culture, lingering anti-Semitism continued in Soviet life.

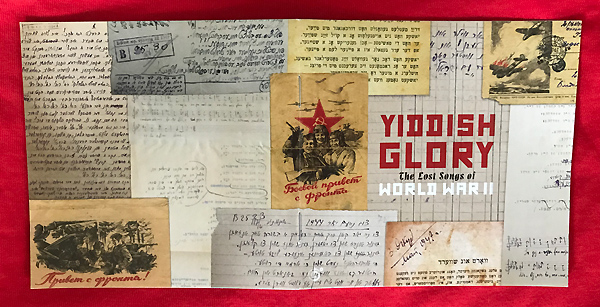

A decade after the end of the Soviet system, Anna Shternshis, by now a University of Toronto professor, arrived in Kiev, where she discovered that these songs had survived all these decades, lying untouched but slowly deteriorating, in the manuscript department of the Vernadsky Ukrainian National Library. These fragile documents, some typed, but most hand-written on poor-quality paper, constituted an emotionally wrenching and historically important archive of amateur, unprofessional, but poignant and timely Soviet Yiddish wartime songs. None of them had been performed since 1947.

The release of Yiddish Glory at least partially vindicates the hopes of Beregovsky and Lerner.

18 tracks, each one a gem

Shternshis has collaborated with the researcher and performer Psoy Korolenko and the violinist, singer and composer Sergei Erdenko, later acquiring a CD producer (Dan Rosenfeld), to “realize” an anthology of 17 of these songs into appealing, performable arrangements. Only a few of the poems they found were accompanied by notated music. For the rest the arrangers delved into the entirety of Jewish music (including folk, Yiddish theatre and liturgical), Russian music (including popular and classical composers, plus the tradition of Russian Orthodox chanting), to create melodies and little sound worlds for these precious, evanescent expressions of passionately lived life. Some arrangements do have some klezmerish qualities, but not everything is turned into a klezmer number. It was evident in some cases that the lyrics were meant to be sung to the tunes of existing Russian or Yiddish songs, and an astute listener is sure to pick some of them up. The program notes are admirably detailed. On one song, the notes reveal, a riff is lifted from Harry Tierney’s 1927 Broadway musical Rio Rita!

Each one, whether kept simple and pure in grief, or fully orchestrated with a chamber ensemble of players for the more exuberant numbers, is turned into a little gem. Given the size of the Beregovsky archive, one can imagine further research emanating from this rich source.

Aside from vocalists Korolenko and Erdenko, the CD features the Russian-born, now Canadian-based jazz singer Sophie Milman, whose grandmother was a survivor evacuated to Kazakhstan, and both of whose grandfathers fought in the Red Army. As Milman has said, “Eastern European Jews, we can’t shake the war. No matter how many generations later, we feel it.” The song “Kazakhstan,” with anonymous lyrics presumably by an evacuated Polish Jewish refugee, is the only one for which entirely original music (by Erdenko) is employed. That song, delivered in a smoky jazz idiom by Milman, is later reprised in a more muscular voicing by Erdenko.

There are songs of intense grief. “Mames gruv” (My Mother’s Grave), written by 10-year-old Valya Roytlender from Bratslav, Ukraine, on August 20, 1945, asks: “Oh, mama, who will wake me up? Oh mama, who will tuck me in?” Twelve-year-old Isaac Rosenberg (related to the producer Dan?) was invited onto the CD to perform this sorrowful lament. I wonder if Valya is still living—he’d be about 83 now.

Other songs openly wear their feelings of resentment and hatred for the Nazis, and the accursed name Hitler appears about as often as Stalin’s. “Afn hoykhn barg” (On the High Mountain), by Odessa-born Veli Shargorodskii, satirizes Hitler’s failed attempt to seize the natural resources he was after in Ukraine, Crimea and the Caucasus. It was recorded in Uzbekistan in the summer of 1944. The Germans had been turned back at Stalingrad the year before, and now “Germany is in trouble, Hitler is kaput!”

Another song in that vein features “Yoshke fun Odes” (Yoshke from Odessa), a raging Jewish butcher who is fully the match of the German butchers who “desolated and destroyed our beautiful city.” In Berta Flaksman’s lyric:

For three full days he hailed them down,

firing one after the other.

Yoshke didn’t stop firing bullets from his rifle,

He bashed those fascists without a care—not a bit of respect!

The mutilated bodies fell near the half-dead covering the earth.

Any question why Yoshke sought just and righteous retribution? Why he might have revered Comrade Stalin?

In the song “Babi Yar,” by Golda Rovinskaya, the poet records her likely eyewitness account of the massacre of 33,771 Jews at a ravine near Kiev in late September 1941. The program note on this broadside suggests that a line in the poem promises that anti-Semitism will never again “step foot in our land” as a foreshadowing of post-war Soviet tension with its Jewish population. For years Babi Yar was a sore point: Soviet officials insisted on memorializing the site as a killing-place of Soviet citizens, without mentioning that they were all singled out as Jews. A poem by Yevtushenko and a symphony by Shostakovich gave prominence to this issue.

“Shpatsir in vald” (A Walk in the Forest), by tailor Klara Sheynis, 25, from Cheboksary in the Chuvashia Region, recounts in waltz time an affecting farewell exchange between two lovers before he goes off to the front. They have obviously spent the night together in the forest. One can only be reminded of Romeo and Juliet awakening together:

See, the sun is already rising,

The world will soon be full of light.

Go, take revenge on the fascists,

My hero will come back with a badge of honor.

But maybe not alive. So many young people’s lives were upended by war and destruction. People hung their futures on slender hopes. So much had to be rebuilt, physically and emotionally, after the war ended.

Triumph

Triumph is of course one of the themes in this collection. More than one song refers to the evil Haman of the Jewish holiday of Purim, who was defeated through acts of bravery by the beautiful Esther and her uncle Mordecai. Haman wanted to kill all the Jews of Persia, and in the end it was the Jews who wound up killing Haman and all his followers. This revenge fantasy had a ready parallel in Hitler, of course. In “Shelakhmones Hitlern” (Purim Gifts for Hitler), an unknown poet wrote

You’ve burned my joyful home

And disgraced my daughters.

You’ve trampled my infants

And sworn to get rid of me too.

Your angry dreams are wild and silly.

We’re alive! And [we] will survive no matter what.

Your bleary end will be on Haman’s tree

While the Jewish people live on and on!

Although many of the songs express explicit internationalist solidarity, it was lyrics like that that troubled Beregovsky and his associates. As good and loyal Soviet citizens they feared recriminations if their project appeared to single out the Jewish people as separate from—or worse, above—the other nationalities of the far-flung Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. Indications of their concern are clear in the notations they made on some of the songs. In “Mayn pulemyot” (My Machine Gun), of unknown authorship, the singer says:

But [luckily] the Red Army is here

And she gave me a machine gun.

I fire at the Germans, again and again,

So that my people can live freely.

For that final line the Soviet Jewish academics substituted, “So that all people should be free.” In the recorded version here, both lines are included.

And humor too

What are Jews without their famous sense of humor, even if in wartime it is often of the gallows variety? The final song of the album is the anonymous “Tsum nayem yor 1944” (Happy New Year 1944), when the end of the war was slowly beginning to come into view:

Some peace and joy around the world

Just to spite those silly little Germans.

Hitler will be thrown around in fiery and icy hells

And he can kiss our….

The salty humor comes in the Yiddish rhyme between “spite” (tselokhes) and the final, discreetly unpronounced word tokhes, meaning “asses.” It’s also a kind of in-joke by the producers who placed the songs in this order, for this is the 18th track (18 being the Jewish number signifying luck and life), so the end is, literally, the end!

You have to trust me that though in English the texts may seem utilitarian and clunky—and there was no attempt made to turn them into English poetry—in Yiddish they have regular rhyme schemes. So joined with the infectious and heartfelt music, it’s quite an upbeat, listenable project.

The CD includes a 44-page booklet with lyrics in English and Russian, with helpful explanations as to their sources and as much information as is known about the poets and the musical sources for the settings. The graphic design incorporates photographs of the original typed or handwritten lyrics as found in the archive, though many of these pages are truncated and used more for visual effect than for actual reading. It is a disappointment that the full Yiddish texts are not supplied, as sung words in almost any language are often indistinct. I would have liked to see them in Yiddish, although as a compromise—which non-Yiddish readers would have appreciated—I would gladly have accepted at least a transliteration into Roman letters.

Back to Stalin: I seriously question a translation in the “Nitsokhn Lid” referred to at the beginning of this review, even though my complaint involves only a single “t.” The booklet has “This Soviet land / With its Stalinist hand / Will show what it can.” But the snippet of Yiddish text which adjoins this translation happens to include that line, and it reads “mit der stalinisher hant.” “Stalinisher” is a compound word combining Stalin with “ish,” so what was meant favorably is “Stalinish” or “Stalin-like,” hardly the more polemical and insulting “Stalinist.”

On the song “Yoshke from Odessa,” referred to above, I can only believe an audio editing mistake was made, because four stanzas are published in the booklet—I quoted stanza three earlier—but we hear only the first stanza twice, followed by a longish instrumental. Maybe in a second edition of the CD this correction can be made.

Another observation: The background material on several of the songs indicates that they were “recorded” in the 1940s by Beregovsky and his team, but further information on the present status of these recordings is scant. It does not appear as though any of those original voices are preserved on the CD.

A video about the history of this project can be viewed here.

A one hour twenty-four-minute video of an entire concert of this music can be viewed here.

Hear Mames Gruv (My Mother’s Grave) here.

Hear Shpatsir in Vald (A Walk in the Forest) here.

Hear Nitsokhn Lid (Victory Song) here.

“The Devastating Resonances of Yiddish Songs Recovered from the Second World War” by Amanda Petrusich (The New Yorker, July 27, 2018), can be read here.

Yiddish Glory: The Lost Songs of World War II

Six Degrees Records, 2018

Producer: Dan Rosenberg

Featured vocalists: Psoy Korolenko, Sergei Erdenko, Sophie Milman