Growers are just beginning to bring this year’s wave of contracted laborers into Washington State for the coming season to pick apples, cherries, and other fruit. The laborers are arriving to just-relaxed COVID-19 health and safety requirements for farmworkers, courtesy of a Superior Court judge in Yakima County, the heart of the state’s apple country.

Meanwhile, a vote nears in the U.S. Senate that would lead to the massive expansion of the H-2A guest worker program, used by growers across the country to recruit these laborers. In 2020, despite the pandemic, growers and labor contractors brought 28,959 workers, nearly all from Mexico, to work in Washington’s fields and orchards, a 10% increase over the previous year. Nationally, the number of H-2A workers brought to the U.S. annually has mushroomed from 79,011 to 275,430 in a decade.

COVID-19 outbreaks struck Washington’s guest worker barracks last April, starting with 36 laborers in a Stemilt Growers housing unit in East Wenatchee. Within months, eight other clusters were found, and by mid-May rural Yakima County had 2,186 cases—122 were reported on May 15 alone—and 73 people were dead.

With 455 infections per 100,000 residents, the county had the highest COVID-19 rate on the West Coast. Then Juan Carlos Santiago Rincon, a Mexican H-2A worker, died in a Gebbers Farms barracks in July. A second death followed a week later—a 63-year old Jamaican farmer, Earl Edwards, who had been coming to Washington State as an H-2A worker for several years.

State health authorities only found out about Santiago’s death through anonymous phone calls from workers. Ernesto Dimas, another Gebbers worker, told the Spokane Spokesman-Review that the company sent workers into the orchards even when they showed symptoms of illness. “You could hear people coughing everywhere,” he said. Sick workers were sent to an isolation camp, but one infected worker, Juan Celin Guerrero Camacho, said, “I got scared seeing what happened—that workers were not getting medical attention.”

The barracks for H-2A workers leave them vulnerable to infections. They are divided into rooms around a common living and kitchen area. Four workers live in each room, sleeping in two bunk beds, making it impossible for them to maintain the required six feet of distance to help avoid contagion. Stemilt Growers says that it has 90 such dormitory units in central Washington, with 1,677 beds, half of which are bunks. It adds up to a “unique risk,” according to a court declaration given last May by University of Washington epidemiologists Drs. Anjum Hajat and Catherine Karr.

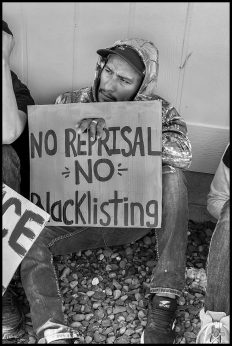

Familias Unidas por la Justicia, the state’s new farmworker union, Columbia Legal Services, and other advocates sued the state a year ago in March, demanding better safety measures. Although they didn’t win a ban on the bunk beds, they did secure other protections, including twice-daily medical checks for workers with COVID-19 symptoms, quick access to emergency services, and clearance for community advocates to contact workers on the farms.

But those victories were invalidated by Yakima County Superior Court Judge Blaine Gibson’s April 21 decision.

In a news release, John Stuhlmiller, chief executive officer of the Washington Farm Bureau, called it a “common sense ruling” and “science-based adjustments.” He called for “repeal or modification” of other requirements, including any limits on bunk beds or other distancing measures, which he had previously labeled “crippling business restrictions.”

Washington State was hardly a fierce enforcer of the regulations. Even before the ruling, the state Department of Health said the monitoring requirements weren’t feasible, and the Department of Labor and Industries said it would not enforce them. State communicable disease epidemiologist Scott Lindquist said in an April 13 court declaration that a daily phone call to a sick worker, from an unspecified source, could take the place of medical visits.

But Edgar Franks, political director for Familias Unidas por la Justicia, said such a measure “wouldn’t have helped the workers who died at Gebbers, since there was no phone service because they couldn’t get a good signal in that rural area.”

Meanwhile, Congressman Dan Newhouse, a grower from the Yakima Valley, has pushed the Farm Workforce Modernization Act through the U.S. House of Representatives, and it now awaits a vote in the Senate.

“The Farm Workforce Modernization Act is the dream of the industry,” said Franks, “because it lets them do what they want with workers, including paying them low wages, and blacklisting and deporting them if they protest. The judge’s recent ruling just gives us a taste of what’s coming down the line. Even the minimal gains we’ve fought for can be taken away, just like that.”

The bill contains a complex and restrictive legalization program for some of the country’s 1.2 million undocumented farmworkers, along with enforcement provisions that would prevent undocumented people from working in agriculture at all in the future.

The bill’s main impact, however, is the relaxation of restrictions on the use of the H-2A visa program, which would likely lead to enormous increases in the number of workers brought to the U.S. by growers and labor contractors.

Dan Fazio, director of the country’s second-largest labor contractor for H-2A workers, the Washington Farm Labor Association, told Capital Press, “the program works, and we don’t have an alternative.”

Even though unemployment skyrocketed during the pandemic, growers claim they couldn’t find local workers willing to pick Washington’s fruit. “We don’t see any effect from the unemployment rate for U.S. workers,” Fazio claimed.

According to Washington State Tree Fruit Association President Jon DeVaney, unemployed people don’t want to work because “they are collecting state and federal unemployment benefits.”

Rep. Newhouse was successful in winning grower support for the bill, but only 30 Republicans voted for it. The bill’s co-sponsor is Silicon Valley Democratic Congresswoman Zoe Lofgren, and every Democrat in the House—except Maine’s Jared Golden—voted for it, even the party’s leftist representatives.

“There’s a real disconnect among policy makers from the reality on the ground,” Franks charged. “They’re preserving a system that is putting workers at risk. With this judge’s decision community organizations and unions are now denied access to these workers, while growers have them in a stranglehold.”

Nevertheless, Stuhlmiller asserted, “We all share the same goal: protecting farm worker health while keeping our farmers in business.”

Within days of the judge’s decision, Gov. Jay Inslee warned, “we now are seeing the beginnings of a fourth [coronavirus] surge in the state of Washington.”

Affected guest workers will no doubt receive a phone number they can call when they get sick.