MEMPHIS—Remembrances of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s ideas, activism, and assassination were prominent parts of the I Am 2018: Mountaintop Conference, but much focus was also given to finding ways to help build the movements activating communities around the country today.

Former President Barack Obama spoke to the crowd in a message during the conference’s 50th anniversary commemoration event, urging everyone to look at King’s legacy as “not a relic of the past but a roadmap to the future.”

But that can’t be done without a serious look back at the 1968 sanitation workers strike, which brought King to Memphis. Three of the original 1,300 sanitation men who were forced to strike that February talked with reporters from People’s World and other outlets at a press roundtable on the sidelines of the conference on April 4, the anniversary of King’s murder.

The 65-day strike began after the deaths of Robert Walker and Echol Cole while on the job. On the afternoon of Feb. 1, with their truck full of garbage and on its way to the dump, Walker and Cole were forced to seek shelter from the rain by riding inside the back of the truck’s garbage hopper. The truck’s compactor suddenly malfunctioned and came down on them, killing both. After their deaths, the city’s public works department refused to compensate their families, arguing that Walker and Cole were “hourly workers” and didn’t qualify.

This was the last straw in a job where the workers earned $70 a week or less—not enough to feed their families—and where their warnings about faulty trucks went unheeded by the white power structure, including their bosses, Memphis mayor Henry Loeb and the city council. Two other workers had been killed in a similar manner four years earlier.

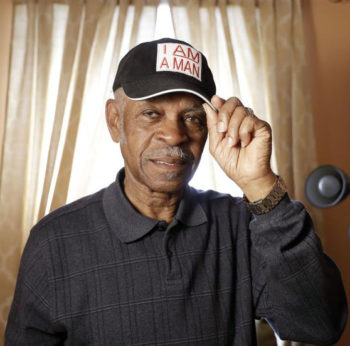

The workers were also denied the right to organize and join the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) to better their wages, protect themselves on the job, and gain the respect that “I Am A Man,” as their now famous signs declared.

Elmore Nickelberry, Baxter Leach, and Rev. Cleophus Smith told reporters about their experiences back then and how they connect to movements right now across the country.

Nickelberry said it was tough to get the job initially. He sat outside the gated lot where the garbage trucks were parked for almost two weeks until someone finally noticed him and offered him work. He needed the job to help feed himself and his family. However, when he learned what sanitation work required of him, he found out it was not what he had bargained for.

At the time, most garbage went directly into big cans or tubs; few people used garbage bags. The most infamous of the tub types was the “number three,” which was notorious for leaking waste onto workers.

“I got a number three tub and that day, I got on the truck and started picking up garbage from people’s backyards…We’d take the number three tub and then we’d start walking yard to yard. Sometimes the tubs had a hole in it and maggots run all down our face. Sometimes, I got inside the truck and when they got to me and taken the tub off their heads and throw it in the truck, maggots got all down my face.”

“When the smell and maggots got in my clothes, I couldn’t ride the bus. I had to walk home, walk about two miles home because I smelled so bad. And after I got home, the wife told me I couldn’t come into the house. She said: ‘You smell so bad.’

“So, she brought me a housecoat and I pulled the clothes off right outdoors there and went indoors to take a shower. We didn’t have any shower to wash our pants or nothing. No bathroom or nothing. We did that part-time. And at the time, it was hard. We were going from yard to yard, and most times you never knew what you were picking up.”

Nickelberry later explained the men picking up the garbage also had to rake the leaves and carry them in the number three tub on their heads to the truck. They also cut limbs off trees in the yards and brought those to the truck. To beautify its white neighborhoods, the city of Memphis had their sanitation workers—who were almost all Black—do gardening in addition to picking up waste for its citizens. And the workers did the job for one reason: There was nothing else out there to help feed their families.

“It was hard. It was real bad during that time because I had to have that job. I had a family—two kids and a wife. A job was important to me at that time because I had a family. I had to do it,” he said.

Men like Nickelberry hauled waste daily, with no access to bathroom facilities, and they were forced to rely on faulty equipment and trucks that were prone to break down. It was one of those obsolete trucks that killed Walker and Cole, kicking off the months-long strike.

AFSCME President Lee Saunders spoke about that time at the I Am A Man strike commemoration in Memphis. He said the sanitation men, virtually all African Americans, endured tear gas, gunfire, and more. One man died in the course of the strike, Saunders said.

The men endured rough treatment every day but stuck it out until the city of Memphis eventually caved. But the city gave in only after King flew to Memphis, marched with “tens of thousands of people” through the streets, rallied the workers and their citizen allies with his famous “Mountaintop” speech at the Mason Temple Church of God in Christ on April 3, 1968—and was assassinated the next day. Enormous pressure forced the city to yield and gave the workers their win, and their union.

Nickelberry explained that after the strike, the tubs were gone, replaced with carts that workers could push around rather than carry over their heads. They also got uniforms, shoes, new trucks, a rain suit, facilities to change in, and things like health care and a more dignified wage. However, just before King came to Memphis, Nickelberry said it was a terrible time. “But, after King came, things started to get better. If it weren’t for him, we’d still be on strike!” Nickelberry said.

“I felt pretty bad” when King was murdered on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel. “A man comes from out of town to try and fight for us…When I think about it, it’s doing something to me now.”

Rev. Smith said conditions for city workers now are almost back to where they were in 1968 because the workers are dealing with things they shouldn’t have to. Raises occurred for 30 years after the strike and then ended, until just a few days before the commemoration. The city also stopped hiring full-time employees, making everybody part-time.

“You got some out there working part-time, who have been there a year to five years with no benefits,” Smith said. He told of a family that went five years without getting a full-time position. He said the workers’ pension was taken away after being in place for over 50 years. The union and activists in Memphis struggled to get it reinstated. That happened last year, followed by the recent raises by a new city administration.

“It’s the good on one side, but it’s bad on the other side. I’m not so much looking at the good for me. I’m looking at the bad that’s happening to other people that we would like to see get the same treatment that we get. So that’s why we are still out there today. April 15 will be 51 years that I’ve been there. It is my intention to stay there until we get these things done,” he said.

But the part-time sanitation workers have no health insurance, pension, or wage stability as the full-time workers do. The problem is much bigger than that as well, Smith explained. In 1968, there were about 1330 full-time workers. Many got fired after refusing to return to work despite the union negotiations that were ongoing at the time.

The city never refilled those slots with full-time workers, they instead replaced the outgoing full-timers with part-time workers, or didn’t fill the slots at all, Smith pointed out. Since then, the city has kept a workforce of about 600 full-time workers and 80 part-time workers.

Leach said kids today must be educated in order to get jobs they will need to support their families. In fact, his words mirror the spirited message Saunders gave at the I Am 2018 Youth Town Hall earlier in the day. The union leader spoke to a group of young people about having a goal beyond high school and working hard to get there.

He also reminded them of their responsibility to mobilize their communities around issues of common struggle. This community activation is the kind of tactic that sanitation workers like Leach, Nickelberry, and Rev. Smith used to bring their city to the table to meet the demands of strikers.

All signs point to an upcoming generation that is on the move. The #MeToo, #BlackLivesMatter, and #MarchforOurLives movements are examples of this generation’s ability to organize when they are passionate about a topic. Building connections with the struggles of the past can sometimes help bolster their cause and fuel their activism when things get grim. That reminder comes from Nickelberry’s poignant story and Smith’s reminder that, although things changed, there is still a long way to go.

Saunders said as this newest generation becomes active, they should be aware of the past and learn from the strategies of those who came before while charting their own way forward.

Mark Gruenberg contributed to this article.