CAMBRIDGE, Mass.––Noted China labor expert, Liu Cheng, Professor of Law and Politics at Shanghai Normal University, is making a tour de force of the U.S. He’s meeting with top labor activists, government officials, and academics, promoting what he describes as a much-needed labor exchange effort to familiarize union workers from China and the U.S. with each other and with their shared challenges.

In addition to his academic work, Professor Liu is Director of the Center for the Study of Chinese Labor Issues and President of the Asian Society of Labor Law. He was an adviser to the Chinese government during the drafting of the 2008 Labor Contract Law, which was adopted by the National People’s Congress in 2007 and went into effect the following year. This new labor law tightened restrictions on private companies and boosted the power of labor unions throughout China. U.S. monopolies and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce in China unsuccessfully lobbied to water down the 2008 law while it was under discussion. Liu testified before the U.S. Congress about their meddling, which awakened some influential labor activists here to a much more nuanced and complex understanding of labor relations in China.

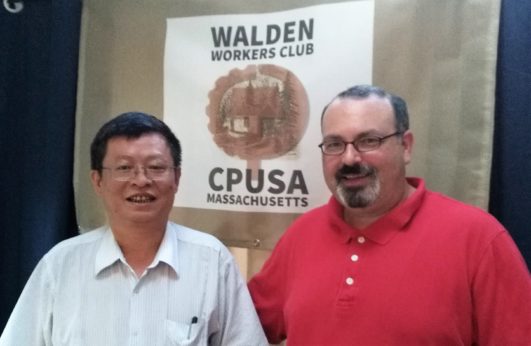

Liu’s visit to the Boston area included a special presentation on the conditions and consciousness of the Chinese working class at the Center for Marxist Education in Cambridge and a dinner hosted by the Walden Workers Club in Central Massachusetts on August 19. He participated in substantive talks with the Massachusetts Coalition for Occupational Safety and Health in Boston and a labor roundtable hosted by the Harvard Labor-Worklife Program in Cambridge on August 20.

During his presentation to labor activists and academics at the Center for Marxist Education, he began with a simple observation: “Capital moves freely across national boundaries, but the workers fight each other!” He continued, “Workers of the world really do need to unite. The good news is, I think there is a willingness and the resources available to begin a U.S.-China labor exchange program that can help to unite workers, but this work takes patience.”

According to Liu, the struggles of working people in the U.S. and China share many similarities and root-causes. Take, for example, the predominance of neoliberal educators in both countries. Although China is a state formed by a socialist revolution in 1949, a combination of market mechanisms and mainstream neoliberal education at Chinese universities has begun to create internal contradictions just like those found in other industrialized countries. While market mechanisms and an opening to Western economic theory were put in place to develop the productive forces of the country, these forces have created growing income and social inequality.

Liu attributes these contradictory political and economic forces to what he terms “free market fundamentalism.” He stresses that there is “a problem of over production…an imbalance between supply and demand.” In Asia, he says, “this imbalance is covered by exports, and in the West, by financial bubbles—the ubiquitous ‘boom-bust’ cycle and predatory consumer credit that periodically leaves millions of workers unemployed and impoverished.”

Far from being an armchair political and economic theorist, Liu previously served on the Binzhou Municipal Planning Commission in Shandong province and later in the Shandong Provincial Auditing Office. In addition to his work in government and politics, his membership and close working relationship with the All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU) spans the course of three decades in which he has witnessed massive overproduction and a fundamental shift in the conditions of the Chinese workplace.

“Overconsumption (net import) in the U.S. and Europe and net export in Asia have covered up overproduction,” Liu emphasizes. “In the past 40 years, production has doubled—this is caused by Wall Street and the neoliberal members of the Chinese academy who were educated by the Chicago School beginning in the 1980s and 1990s.”

When U.S. labor activists ask Liu what model needs to be embraced to make change, he says, amusingly, “Let’s go back to examining the Labor Theory of Value contained not only in the work of Marx, but also Adam Smith.” Liu pointed more than once to the importance for U.S. and Chinese workers to understand and revisit the growth of inequality. According to Liu, this is one of the reasons why we need more labor exchanges.

In terms of the ACFTU and the conditions and class consciousness of workers in China, Liu recommends the building and strengthening of grassroots, democratic unions combined with long-term exchanges with other federations and unions outside of China to learn from the experiences of other industrial and post-industrial workers’ movements.

At the meeting with Massachusetts Coalition for Occupational Safety and Health (MassCOSH) on Monday, August 20, Liu indicated his intent to convene a conference in Shanghai to advance international labor cooperation around occupational safety and health tasks, and to invite MassCOSH and U.S. unions to send representatives.

While speaking later that day at the Harvard Labor/Worklife Program, Liu outlined two crucial elements needed for Chinese unions to be more effective. The first is direct election of union officials. Today, elections are held in some unions, but they are not required. The provincial and local leaders of the ACFTU are largely appointed by provincial and local governments. This causes conflicts of interest and removes workers from the democratic process. Secondly, he argues that the Chinese government needs to litigate on behalf of workers—including individual workers. Liu explained that the ACFTU can be ineffective because neither it, nor the labor law (until 2008) were designed to address the presence of private ownership and employers. That is changing, but slowly, according to Liu.

Another significant challenge to bolstering the strength of workers in China and the U.S. is their lack of ideological education. In China, Liu says, “The government downgraded ideological education of workers when the market mechanisms were introduced. Young workers are conscious of their rights, but class consciousness is another matter.” To move forward, Liu recommends that unions participate more fully in policymaking to address the serious inequalities facing especially migrant workers in China.

Liu believes that the next steps taken by U.S. and Chinese workers should be to meet each other and learn together, working side-by-side. “The world is changing. We need to find new tools, measures, and instruments. We need more social organizations to get involved in the workers’ struggles. We cannot expect the rise of unionism again, as you had in the U.S. during the 1940s and 1950s, therefore we must find new measures and methods to move forward.”

Liu’s stop in Cambridge was part of a tour across the U.S. stretching from August 5 to September 1. He began in California, visiting the Labor Center at the University of California, Berkeley. While in the Golden State, Liu also met with the U.S.-China People’s Friendship Association and the Niebyl-Proctor Marxist Library in Oakland, and then traveled south to meet with the UCLA Labor Center. From August 12-18, he held a series of meetings in Washington, D.C. at the Department of Labor, the Department of State, the AFL-CIO, and at SEIU headquarters. He will continue his visit with further meetings in Cambridge and the San Francisco Bay Area before returning to Shanghai.