Earlier this month, former Singaporean Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong was asked by a 70-year-old resident if the government could cut its lawmakers’ sky-high pay to fund pensions for the elderly.

Goh’s response was the same one that Singapore has always trotted out to explain its generous salaries: Cutting ministers’ pay would be “populist” and a bad move, because it would be hard to persuade high-flyers in the private sector to give up their top-dollar jobs to get into politics. “You are going to end up with very, very mediocre people, who can’t even earn a million dollars outside to be our minister,” he said.

If we adopt this logic, then the characters of Crazy Rich Asians must be the cream of the crop in Singapore. They are, after all, crazy rich. That’s the only Singapore we get to see on screen—and it’s a sign of the direction Hollywood is taking its depiction of Asia.

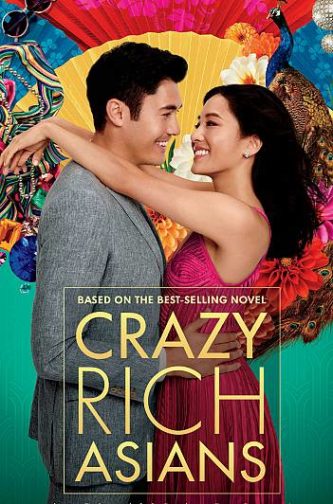

Crazy Rich Asians, based on the novel by Singaporean-American author Kevin Kwan, premiered in Los Angeles to enormous fanfare. The film, which will open in Singapore—where most of the story is set—on Aug. 22, follows Chinese-American Rachel Chu (played by Constance Wu) as she follows her boyfriend, Nick Young (Henry Golding), back to his hometown to attend his best friend’s wedding and meet the family. The family, as it turns out, is ludicrously rich, and so Rachel gets sucked into a world of extravagance and eye-watering wealth.

As the first Hollywood-produced film in a quarter of a century to feature an all-East Asian cast, Crazy Rich Asians has been heralded as a watershed moment for representation and diversity. Many Asian-Americans, long starved for seeing people like them on the big screen thanks to Hollywood’s penchant for whitewashing, are unsurprisingly elated. “It’s not a movie, it’s a moment,” gushed the Guardian. A writer for Vox was so excited he declared the film “The Best Movie About Asian People in Decades and the Best Rom-Com of the Summer.”

But what of Singapore? Most of the story is set here, and the majority of the characters are meant to be Singaporeans. The Crazy Rich Asians team has talked a lot about the politics of representation, telling the Hollywood Reporter that care was taken to avoid cultural clichés and blind spots. Yet it’s important to remember that, from the book through to the film, the presentation of the Southeast Asian city-state is about as reflective of Singapore as Gossip Girl is of America.

In a country where elderly people still collect cardboard on the streets to scrape together a few dollars and low-wage migrant workers are often shortchanged for the hard labor they’ve performed, the media depiction of it always focuses on the gentrified neighborhoods, the tourist-friendly hawker centers, and the Marina Bay Sands, one of the most expensive buildings in the world. Crazy Rich Asians is no exception. Singaporean actors weren’t able to speak as much Singlish—a local patois sometimes frowned upon by the government—in the film as they had hoped. The Singapore Tourism Board must be over the moon with this portrayal of a manicured, glossy city.

Then there’s the film’s most glaring erasure, more egregious than any failure to feature the public housing estates in which 80 percent of the country’s resident population live.

Crazy Rich Asians erases Singapore’s sizeable non-Chinese population—15 percent of the island’s citizens are Malay, and 6.6 percent are Indian—relegating the country’s ethnic minorities to backdrop characters who open doors and guard mansions.

The film’s producers are well-versed in American racial politics and white dominance but don’t seem to have realized that, in the Singaporean context of power and privilege, Chinese Singaporeans—especially the super-rich ones—are the “white people” here. Without this recognition, they came to Singapore and ended up replicating precisely the power dynamics they claimed to be fighting against in the United States.

Of course, the film was never meant to be everything to everyone. As the title tells us, it’s about a very specific, very exclusive segment of the Singaporean population. It’d be unreasonable to expect it to please everyone, and there’s an argument to be made that it’s being so heavily scrutinized precisely because there are so few Hollywood-backed films about Asians and Asian-Americans.

The film’s producers are well-versed in American racial politics and white dominance but don’t seem to have realized that, in the Singaporean context of power and privilege, Chinese Singaporeans—especially the super-rich ones—are the “white people” here.

But would the white Hollywood executives who backed the film have done so if it hadn’t been about over-the-top Asian wealth? If Rachel Chu had come to Singapore and Nick Young’s family turned out to be living in a public housing block, struggling with the cost of living—perhaps more like the families depicted in the critically acclaimed Singaporean films Ilo Ilo and Singapore Dreaming—the issues of identity, belonging, and place would arguably have been even more interesting than in a context where one can literally buy one’s way around racism. But would Hollywood even have been interested?

Singapore has long been seen as a playground for the super-rich; in the 2018 Knight Frank Wealth Report, the city-state tied with Chicago in fifth place on the overall Wealth Index. It’s an image the Singaporean establishment is more than happy to buy in to—the government refuses to set a poverty line and rejects the idea of a national minimum wage. As we see from Goh’s comments, Singapore is a place where the size of one’s bank account is linked to the notion of one’s worth.

The indulgent decadence of Crazy Rich Asians plays straight into this idea, and also the broader trope of an ascendant Asia, where East Asia—once seen as the home of exotic conical hat-wearing peasants—is now an economic power to pay attention to, with Chinese speculators making their presence felt in Western markets.

There’s another way in which the film’s title can be read: These aren’t just crazy rich Asians, they’re crazy rich Asians. It’s drawn from author Kevin Kwan’s own experience growing up among Singapore’s wealthy elite, but it’s not meant to be a lifestyle for the majority of audiences to identify with. It’s meant to be a lifestyle for audiences to gawp at.

Sure, it can be fun to watch rich people parade about, wearing things we could never imagine hanging in our own closets and partying hard without ever having to worry about the bill. But portrayals of the vastly wealthy in faraway climes can also be othering. Watching Asia’s moneyed classes fling their wealth around doesn’t tell one very much about the realities of life for billions of people in Asia; it’s mostly exoticized fantasy.

“[W]henever the exploits of rich Chinese people are reported for the consumption of Western readers, these accounts are unabashedly Orientalist,” the American journalist Pooja Makhijani wrote about the Crazy Rich Asians book series in her review of second installment, China Rich Girlfriend. “It is only the inclusion of Rachel Chu, the Chinese American interloper through whose eyes we view these excesses, that obfuscates this claim to the Western reader. But as I’ve learned, even being an American person of color does not wholly erase one’s American point of view.”

Race and the politics of representation have made Crazy Rich Asians a more scrutinized film than such a rom-com would otherwise be. It’s a huge burden to carry. The hope is that it’ll pave the way for more films centered on a variety of Asian-American experiences—a highly desirable development, even from the standpoint of a non-American Asian.

But for Singaporeans like me who’d hoped that this story would be a chance for a more nuanced representation of our country than as a smoky pirate haven on stilts (Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End) or a soulless background for super-soldiers (Hitman: Agent 47), it’s clear that this is an Asian-American milestone, not ours.

“They talk about cultural appropriation,” a friend remarked after having watched the film. “But they appropriated Singapore.”

This review originally appeared in Foreign Policy. It is reprinted here with permission.