CHICAGO—“If we want to break the school-to-prison pipeline, if we want to abolish the prison-industrial complex, if we want to create schools that nourish the intellectual imagination of younger generations, then we have to dismantle the structures and ideologies of racism, and we need to start right now.” That was the message radical activist, philosopher, and professor Dr. Angela Davis brought to a meeting of educators and activists at a “consciousness-raising” event sponsored by the Chicago Teachers Union Foundation on June 16.

This year’s state-by-state uprisings of teachers demanding a better public education system perhaps owes its inspiration to an earlier, and continuing battle, waged by the Chicago Teachers Union (CTU) in their monumental strike of 2012, led by labor leader Karen Lewis. They helped put the spotlight on the profit-driven attack on public schools and through their philanthropic arm, the CTUF, they are still at it. The intersection of struggles around education and the juvenile and adult criminal justice systems was the topic of the event featuring Davis, who pinpointed the systemic oppression and exploitation at the heart of the matter.

Moderating the program was Dr. David Stovall, a University of Illinois at Chicago professor and author who studies the influence of race in education, housing, and community development. In introducing Davis, he spoke of the need for those who do justice work to get recognition for all the names of the people who go unknown, whose names go unspoken. Referencing the recent multiple disappearances and murders of young Black women in Chicago, Stovall explained that the city and society, has declared them “disposable.”

“We have to be clear what our work is, not just as Chicagoans, but as citizens of the world,” Stovall said. His intro served as the perfect lead-in for Davis’s remarks on the intersection of schools, prisons, and the disposability of people under capitalism.

Education as a democratic right

Davis said Chicago teachers and education activists are on the front lines of a fight with national and global implications. “The safeguarding of education from privatization, commodification, marketization, and however else you want to convey the relationship [of education] with capitalism,” she explained, is essential in protecting the democratic right to education.

“If you take democracy seriously, then you have to take education seriously as well, because at its best, education allows for the practice of democracy. The classroom should be a space where students learn how to practice radical democracy. But we are witnessing the exact opposite trend. [We are witnessing] privatization of schools, and deterioration of education as a public good,” Davis argued.

Again highlighting the experience in Chicago, she pointed out a number of “school reforms” pursued by the Rahm Emanuel administration and said the city has seen the emergence of pilot programs for “a neoliberal education strategy that is explicitly designed to devour public education in the entire country.”

Such moves toward the dismantling of the democratic right to education have “a clearly racist dimension,” she said, referring to the fact that many of the students in the public school sector are children of color. “When you talk about public education, you’re talking about the education of Black and brown children,” Davis emphasized. “Attacks on public education are attacks on communities of color and poor communities.”

Capitalist corruption of education

Davis explicitly made the connection between global capitalism and neoliberal ideology and the attack on education.

“It is only by understanding the extent of the drive for profit during this new stage of capitalism that we can apprehend the intensification of racism, the emergence of a prison-industrial complex, the replacement of mental health facilities, employment, recreation, etc., with incarceration.”

Understanding this larger context makes it possible to connect “the assault on youth, especially youth of color, the escalation of misogynist violence, the rise of gun violence, the deterioration of housing and schools, and the use of incarceration as a strategy of amnesia to the problems of racism, Islamophobia, poverty, and a whole host of other domestic and global issues,” she explained.

Davis said twenty years ago simple slogans like “education not incarceration” and “schools not jails” were standard, but the movement failed to sufficiently realize at that time the “particular way in which schools in Black and brown communities were being retooled, so as to produce a human product that had nowhere to go but through the pipeline of the juvenile justice system or the prison system more generally.” She stressed the need to embrace transformative strategies for not only the justice system, but for the educational system as well.

“As teachers we must be aware of the extent that what often pretends to be education can serve as a barrier to the development of critical thinking.” Referencing the school-to-prison pipeline, she brought up a new concept, the “prison-to-school pipeline,” which encapsulates the ways in which schools are themselves becoming more like prisons—places for discipline, correction, and punishment. Davis noted that “even if schools do not push certain students to the prison pipeline, they can still thwart the development of these students, [such] that these students fail to embrace the future.”

Speaking to the importance of fostering imagination in education, Davis explained, “It is only through the imagination that we reinvent ourselves and our relation to others.” But in the era of neoliberalism, education has been instrumentalized, she argued. “It has been reconceived as a means of acquiring more—more money, more commodities, more and more. And of course capitalists always want more profit no matter how much they have. Knowledge at its best is about transforming our world. Making life more habitable for humans and other beings, and about preventing the destruction of the planet itself.”

Instrumental knowledge under capitalism cannot appreciate “the broad sense of the contributions our generations can make to the history of this planet. [Capitalism’s version of knowledge] may allow us to figure out how to produce more, acquire more, and ultimately destroy more, but it will not give us an ethical sense of our responsibility to the history of living beings.”

Abolition as a strategy

Davis also discussed the usefulness of the strategy of intersectional feminism for dealing with systemic oppression under capitalism. “Connections are denied in popular political discourse,” she noted, bringing up the correlation between various political happenings since the 1970s, from attacks on working people and labor unions to the emergence of the prison-industrial complex.

“Privatization of everything; schools aren’t alone,” she said. “Feminist approaches are important because they help us understand affinities and relations—especially in cases that appear to reveal disconnections and discontinuity,” she explained. Many of these struggles that may seem unrelated are in fact linked.

Stressing the need to challenge the structures and ideologies of racism—whether in schools or in prisons—Davis emphasized that the elephant often in the room but not discussed is capitalism.

“It is this capitalism that continues to rely on racism for its capacity to justify super exploitation and to create surplus disposable populations that can be disregarded, incarcerated, subjected to police violence and torture,” she said.

Davis explained that the abolitionist approach to the prison-industrial complex was about abolishing the conditions, such as systemic oppression, that lead to the creation of the pipeline in the first place.

Black women’s leadership and the alternative to capitalism

In a conversation with People’s World immediately following her talk at the CTUF, Davis offered specific political advice to young women who have been galvanized by the recent movements of #MeToo, #TimesUp, and other struggles for equality on and off the job. “It’s important to allow the realities themselves to speak to them when organizing,” she said.

Speaking particularly to the leadership role Black women play in politics and organizing, she went further: “Black women have always grasped the intersectional character of us being in the world. Particularly now it’s important to make the connection between labor organizing, combating sexual violence, and recognizing the repressive apparatus of the prisons, and the police. The advice I would give would be to stay connected to that tradition [of intersectionality], and not try to simplify what appears to be very complex. To recognize it, you have to take into consideration race, class, gender, sexuality, ability, and so on.”

When addressing the problem of capitalism, People’s World asked Davis how to introduce discourse around an alternative to the current system. “That’s where organizers come in. Organizers have to create a popular vocabulary and a way of thinking about capitalism that will allow people to give voice to the frustration they already feel,” she answered.

“We have to say a form of socialism [is the road forward]. We’ve seen the relative success of socialism in places like Cuba. There are examples we can point to, but it’s not about replicating what someone else has done, but fulfilling the potential which exists here.”

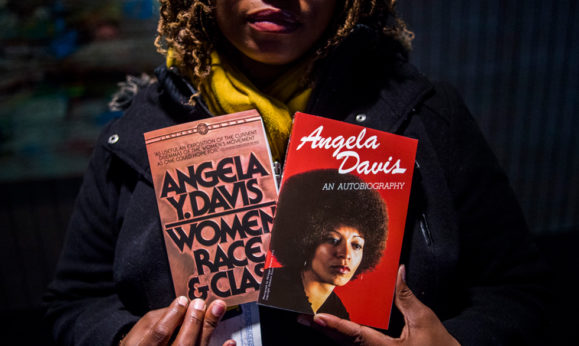

Angela Davis’s most recent book, Freedom Is a Constant Struggle: Ferguson, Palestine, and the Foundations of a Movement, is out now from Haymarket Books. Her Autobiography is available from International Publishers.

Like free stuff? So do we. Here at People’s World, we believe strongly in the mission of keeping the labor and democratic movements informed so they are prepared for the struggle. But we need your help. While our content is free for readers (something we are proud of) it takes money — a lot of it — to produce and cover the stories you see in our pages. Only you, our readers and supporters, can keep us going. Only you can make sure we keep the news that matters free of paywalls and advertisements. If you enjoy reading People’s World and the stories we bring you, support our work by becoming a $5 monthly sustainer today.

Comments