Lewis Hine’s iconic images captured the harsh realities of a country undergoing deep transformation during the early part of the 20th century.

Hine was born in 1874, in a small town in Wisconsin, and when his father died he was forced to become the family’s breadwinner. After a series of poorly paid jobs, he attended night classes to educate himself and was able to obtain a degree in pedagogy, before going on to study sociology under John Dewey.

In collaboration with the Felix Adler Ethical Culture School which ran classes for deprived children, he started to learn the practical and technical aspects of photography. He is encouraged to document the activities of the school—and thus begins what will become a life-long commitment and passion for documenting the social and working conditions of North America’s laboring classes.

Hine prepared slide shows and made them available on loan, and organized exhibitions to make his work widely available. With his child labor photos, he became a forerunner of social documentary photography, bringing social problems to the attention of the US public. His images of child labor in the cotton spinning mills, mines, strawberry fields, tobacco and beef farms during the first decades of the 20th century are reminiscent of descriptions given so vividly by Friedrich Engels of Britain’s industrial revolution during the 19th century.

The National Child Labor Committee (NCLC) used Hine’s persuasive imagery for its own propaganda purposes. Child labor at the turn of the century was widespread: In 1910, over a million children either didn’t go to school at all or only irregularly because they had to work. Hine, as a teacher, had a rapport with the children and talks to them, using what they tell him in the captions to his photos. Only in 1938 would a Fair Labor Standards Act come into force, banning child labor.

Hine also took a whole series of photos on Ellis Island, documenting the tribulations of immigrants seeking asylum in the U.S. He traveled thousands of miles documenting the country’s laboring classes, depicting them in all their vulnerability and dignity.

His work is almost all black and white portraits. At that time, photographing people in motion was not possible given the available glass plate technology, and without the highly sensitive film stock that came later on.

He clearly identifies with the children and the men and women whose labor made the U.S. what it would become: the world’s leading industrialized nation. It is in the faces that we see the hardship, poverty, shame, and abuse. But despite the fact that Hine sees and documents the relationship between industrial production and human misery, he appears to show little curiosity about the economic forces behind this exploitation, and remains seemingly apolitical, as if he fears losing his observer status.

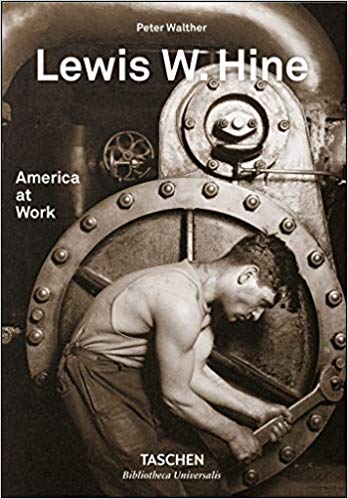

His images have a direct, communicative character, with no self-conscious artiness about them. Hine went on to cover the First World War for the Red Cross, and was the official photographer during the building of the Empire State building, bequeathing us awe-inspiring images of those heroic men who risked their lives to erect this symbolic New York skyscraper.

He went on to work for Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration, but from the 1930s commissions declined. He had set up his own photo lab in New York and advertised as a ‘social photographer’, but his work at the time was hardly recognized as art and he found it increasingly difficult towards the end of his life obtaining commissions. He died in poverty in 1940.

In 1977, his work was rediscovered and is now considered to be invaluable not only as a historical document but as great art. One of his students was the photographer Paul Strand, who carried on his tradition.

This beautiful Taschenbuch edition does Hine justice by bringing his searing images to the eyes of a new generation and reminds us all where we’ve come from.

Lewis W. Hine: America at Work by Peter Walther

Publisher: TASCHEN

Language: English, German, French

Hardcover, 544 pages, U.S. price $20

This article appears on CULTURE MATTERS, a collective of writers and activists who have come together to provide web space and editorial and technical support for a ‘broad left’ cultural struggle for a better society.